S. Linebaugh interviews author Bill Lambrecht

2/23/14 Linebaugh interviews author Bill Lambrecht

“I’m a black- hearted dog,” author Bill Lambrecht confesses in Big Muddy Blues. “Th e contempt American Indians feel towards me at the moment might even rival the store they reserve for the Army Corps of Engineers.” Lambrecht’s nonfiction is like this, telling a big story in personal terms, sweeping the reader with him on a journey of discovery. At the time Bill describes himself as a black-hearted dog, he’s crawling along the shoreline of the Missouri River, slipping bits of ceramic and ancient tools into his pockets. When his fingers touch what he knows is a human bone, he panics, takes to his canoe and paddles away as fast as he can. He isn’t fleeing a recent homicide, but a relic of ten thousand years of Native American history. Lambrecht tells me, “There’s sense of the sacred. To even touch those remains or pick them up is not the way to do things.” Knowing he has no right to the artifacts, he paddles back upstream and scatters his finds in the mud of the river. Later in his motel room he finds, still caught in his pocket, the tiniest of spear points.

e contempt American Indians feel towards me at the moment might even rival the store they reserve for the Army Corps of Engineers.” Lambrecht’s nonfiction is like this, telling a big story in personal terms, sweeping the reader with him on a journey of discovery. At the time Bill describes himself as a black-hearted dog, he’s crawling along the shoreline of the Missouri River, slipping bits of ceramic and ancient tools into his pockets. When his fingers touch what he knows is a human bone, he panics, takes to his canoe and paddles away as fast as he can. He isn’t fleeing a recent homicide, but a relic of ten thousand years of Native American history. Lambrecht tells me, “There’s sense of the sacred. To even touch those remains or pick them up is not the way to do things.” Knowing he has no right to the artifacts, he paddles back upstream and scatters his finds in the mud of the river. Later in his motel room he finds, still caught in his pocket, the tiniest of spear points.

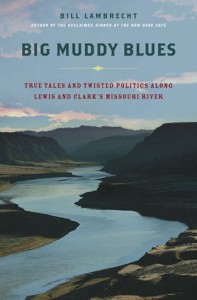

SL: The subtitle of Big Muddy Blues is its synopsis: True Tales and Twisted Politics along Lewis and Clark’s Missouri River. How did you come to your subject?

SL: The subtitle of Big Muddy Blues is its synopsis: True Tales and Twisted Politics along Lewis and Clark’s Missouri River. How did you come to your subject?

BL: Because I grew up in St Louis, I’m interested in the politics of rivers no matter where I live. In the book I provide a lot of spinach in the form of science, and policy, and bureaucracy. Then I have to provide dessert and other types of fare. For the newspaper, I’m the sleuth and the writer, but it’s rare to use first person, (though not so much in blogs). I think I used first person only one time for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. I was with a number of Haitians on the high seas when we ran into a US embargo and were taken into custody.

SL: What kind of research did you do for Big Muddy Blues?

BL: I traveled the Missouri River on assignment and on vacation, attending high-stakes meetings, talking to stake-holders—Indian tribal leaders, politicians, the Army Corp of Engineers, biologists, fishermen—and canoeing on the river between Montana and its confluence with the Mississippi in St. Louis.

I read many books on Indian lore and Indian history. I found that as late as the middle of the 20th century, the U.S. government was still carrying out programs against the best interests of the Indians. For instance, the Pick-Sloan Act of 1948 said the best land belonged to the Army Corps of Engineers. I spent time with a number of Indian tribes. Tribes like the Mandan—the tribe that saved Lewis and Clark’s bacon—have trouble recovering from the loss of 1000 miles of prime land.

SL: What surprised you about the Missouri?

BL: I read so much about how the Army Corps of Engineers quietly diminished it’s beauty, building a half dozen dams between Montana and South Dakota, and blowing up sections of the lower third to make a long straight canal to bring barge traffic. But the barges never came. They’re almost nonexistent below Kansas City. Because of that I surprised by the beauty I found, mostly in the upper reaches, but also in the lower with the bluffs and the solitude. There isn’t much of a residential presence along the river because of flooding. The Big Muddy is fickle indeed, leaping out of it’s banks and meandering through the countryside despite the efforts of the Corps.

SL: How does your approach on Big Muddy Blues compare with your work on your earlier book?

BL: Both books were similar. I did a lot of travel and I turned what I’d done for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch into book form. For Dinner at the New Gene Café (subtitle: How Genetic Engineering is Changing What We Eat, How We Live and the Global Politics of Food) I traveled in Europe, India, South America, and the American South as people were meeting this powerful new building block of technology [GMOs] for the first time. Ten years on, people still call me about that book.

SL: What do you like best about your books?

BL: New Gene Café was more reviewed and is still selling, but, I like Big Muddy Blues. When you can open a book and enjoy your own writing, that makes it worthwhile.

SL: What’s next?

BL: Nonfiction is very hard work and I don’t have any good nonfiction ideas right now.

SL: I know you’re writing fiction. Tell me what.

BL: I’m marketing two fiction books. The first, set on an Indian reservation is a quest to learn what happened to the skull of a famous Indian leader that was scavenged from a grave by a well-known American artist. It’s based on a true story. A tribal elder asked me if I would help him. I did some research at the Missouri historical society and found out his claim was true. That was the seed of a novel that’s now in rewrite.

SL: And the other?

BL: It’s set in Yemen where I’ve spent time. It’s about the cyberworld. An out-of-work journalist searches for a missing neighbor and unwittingly becomes part of a search for a famed teen hacker whose motives are unknown.

SL: Your fiction continues your two approaches. The first is like Big Muddy Blues where you explore how the present compounds the wrongs of the past. The second is like New Gene Café, exposing how the present is creating the wrongs of the future. I’m eager to read them both.

Bill Lambrecht worked for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for more than 30 years, as an award-winning reporter and as D.C. bureau chief. In 2013 he joined Hearst Newspapers’ Washington Bureau as an investigative reporter. His nonfiction books are Big Muddy Blues: True Tales and Twisted Politics along Lewis and Clark’s Missouri River (St. Martin’s Press, 2005), and Dinner at the New Gene Café: How Genetic Engineering is Changing What We Eat, How We Live and the Global Politics of Food (St. Martin’s Press, 2001). He’s currently marketing his two fiction books.

Sonia Linebaugh

Sonia L. Linebaugh is a freelance writer and artist. Her book At the Feet of Mother Meera: The Lessons of Silence goes straight to the heart of the Westerner’s dilemma: How can we live fully as both spiritual and material beings? Sonia has written three novels and numerous short stories. She’s a past president of Maryland Writers Association, and past editor of MWA’s Pen in Hand. Her recent artist’s book is “Where Did I Think I Was Going?,” a metaphorical journey in evocative images and text.