Suspending Disbelief: A Tricky Road for Readers, Writers

1/07/15 — SUSPENDING DISBELIEF: A TRICKY ROAD FOR READERS AND WRITERS

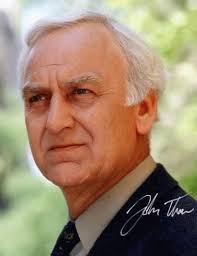

I was watching one of the earlier Inspector Morse mysteries, on PBS the other night, thoroughly enjoying John Thaw’s rendition of a crotchety, alcoholic Morse, when quite suddenly I turned away in disgust. Amidst a complicated series of seemingly unexplainable events, Morse abruptly announced that the murdered drug dealer wasn’t the murdered drug dealer but a doppelgänger who in fact had been killed by the drug dealer. Never mind that Morse had never met either the real victim or his double or the absence of any clues that might have led him to his conclusion. It was the worst kind of deus ex machina, and it totally destroyed the experience for me. And unfortunately that’s been happening to me a lot, both in films and in books.

I was watching one of the earlier Inspector Morse mysteries, on PBS the other night, thoroughly enjoying John Thaw’s rendition of a crotchety, alcoholic Morse, when quite suddenly I turned away in disgust. Amidst a complicated series of seemingly unexplainable events, Morse abruptly announced that the murdered drug dealer wasn’t the murdered drug dealer but a doppelgänger who in fact had been killed by the drug dealer. Never mind that Morse had never met either the real victim or his double or the absence of any clues that might have led him to his conclusion. It was the worst kind of deus ex machina, and it totally destroyed the experience for me. And unfortunately that’s been happening to me a lot, both in films and in books.

Almost all fiction requires a suspension of disbelief. We as readers accept that and even want it. We pick up a novel quite willing to put aside real life and enter a make-believe world. The ability to do that is one of the real pleasures of fiction. A good novel will lift us out of the humdrum of our everyday lives into a more exciting world—or at least into someone else’s more interesting humdrum. But our willingness to enter a fictional world, what John Gardner famously described as the dream of fiction, is predicated on an assumption that the author will take the responsibility seriously and make a determined effort not to disrupt our dream state. We’re quite happy to “go with the flow” without questioning every action as long as the characters are consistent, the plot makes sense according to the rules the author has established, and any departure from the rules is adequately explained and fairly presented.

I’m a fan, for example, of Lee Child’s Jack Reacher novels. Now Reacher is hardly a guy who makes any sense in my real-life world. He travels the country with nothing but a toothbrush and a credit card he uses to buy food and new clothes at Wal-Mart when whatever he’s wearing gets dirty (every few days or so). And he regularly fights his way out of dire situations single- handedly by overwhelming dozens of heavily armed bad guys. None of this bothers me in the least because Child has set clear ground rules and sticks to them. I accept Reacher as a super-hero who has his own code of behavior because it’s consistent and makes sense within the world Child has created. The same is true of many fantasies. Once a new world has been created and explained, I’m good to go. What I can’t tolerate is when the rules change, when characters who were never able to time travel, for example, suddenly get in a jam and discover the new power they never had before.

The point is that when a book or a movie is working well, we become so engaged in it that we get caught up in the action and don’t sweat the little stuff. In a crime drama, we don’t care if the DNA results are available almost immediately even though we know in real life the process can take weeks. And we don’t get too concerned about searches without warrants or interrogations without lawyers. We do, however, get upset when a criminal mastermind inexplicably confesses to an unsolvable crime or the detective in charge suddenly reveals evidence he’s been hiding for 200 pages or for 45 minutes of an hour-long TV show. That’s because we mystery readers like to play along and try to solve the puzzle ourselves. We want a level playing field.

Mystery and fantasy writers have particular responsibilities to keep readers in the dream state, but authors of realistic fiction must carry the load as well. In fact, it may be even more important and more difficult in realistic fiction because it more closely resembles real life. This is why it’s so important for a character to stay in character—and not suddenly act in a way that makes us shake our heads.

It’s not hard to see why writers resort to a phony deus ex machina to get themselves out of a jam. Like all authors, I’m well acquainted with plot holes. I once wrote a mystery chapter by chapter without knowing what would happen next or who the villain would be. Big mistake. You may think it will be fun to figure out who the bad guy is along with your readers, but it’s a sure way to write yourself in a corner and find yourself grasping for the improbable exits that stretch a reader’s patience. It’s what separates the amateur from the professional. And in this day and age, when readers and viewers have so many more choices, it’s almost always fatal.

Mark Willen

Mark Willen’s novels, Hawke’s Point, Hawke’s Return, and Hawke’s Discovery, were released by Pen-L Publishing. His short stories have appeared in Corner Club Press, The Rusty Nail. and The Boiler Review. Mark is currently working on his second novel, a thriller set in a fictional town in central Maryland. Mark also writes a blog on practical, everyday ethics, Talking Ethics.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(48)