5/1/15 Guest Blogger Joseph D Haske, author of North Dixie Highway

A significant turning point in my writing occurred when a fiction mentor reminded me that the simple concept of originality is a critical but often overlooked key to great writing. He said, of a story I’d just finished, “Yes, it’s good, very good. Well-written. But it sounds like Proust. Problem is, thousands of competent, contemporary writers sound like Proust.” I asked him what I should do about it and he told me, “Don’t sound like Proust when you need to sound like Haske.” He encouraged me to trust in my own voice, knowledge, origin, and experience, in order to infuse these elements into my fiction. “Artists who aspire to greatness must do this,” he said. “They trust in what they are, rather than trying to imitate the style and voice of others. Genius inevitably emerges from originality, not imitation, and if any writer truly wants a shot at immortality, the best road to follow is one’s own.” Ever since that day, I’ve tried my best to stay true to the essence of who I am and where I’m from, and this awareness has certainly informed my approach to fiction.

What would prompt a writer to stray from originality? The simple answer might be fear. It’s easier to observe and follow the roads that have led others to success than to break new ground. In the case of someone such as myself, other factors intensify this fear. From an early age, working-class and poor people are taught to conform; we are coerced to worship at the heels of those who embody some implicitly unattainable ideal, especially in academic, social, and artistic environments. We’re often told that we’ll never quite reach the top, regardless of our achievements or talent, but if we accept our subordinate place and obey the rules, we might be fortunate enough to catch some table scraps here and there. Those of us who choose not to conform soon find that most of the world is against us, and there’s no safety net if we fail. There are limitless complications as it is for writers in a society that shows little concern for artistic endeavors, and this situation proves even more difficult for artists who are economically and socially disadvantaged: we have a perpetual chip on our shoulders, because, regardless of our achievements, it always seems as if there’s something more to prove or we’re looked down upon for not having the right pedigree. We’re often reluctant to write about the characters, places, and experiences we know best for fear of affirming other’s suspicions of our literary inferiority, despite the fact we may have attained a solid education and we might have read as many great books as anyone else while tirelessly honing our craft. There’s safety in conformity, especially in a system that equates poverty with ignorance, so it’s tempting to go with the flow and produce the sort of writing that conforms to reader’s preconceived expectations of “contemporary American literature.”

Of course, the current state of art in society and the treatment of literary writing in general is a problematic issue, regardless of the social class, race, or gender of the writer. The corporate trend that has overtaken the literary world has contributed to this climate of uniformity, safety, and aesthetic stagnation. Recently, the former editor of a prestigious literary journal explained to me why he stepped away from his position from that journal after many years and so much hard work. His simple explanation was that he no longer believes there’s much to be admired in contemporary writing. He made some strong points, citing a lack of originality in plot, style, and voice in the vast majority of fiction submissions he’d read over the course of the past few decades. However, despite what he and many others believe about the state of contemporary literature, it is my belief that there is just as much, maybe more, great literature produced now than ever before. One problem that a reader faces, though, is that there is just so much to sift through, and who has the time? Also, more than ever, a primarily corporate model for literature largely dictates what people read. That isn’t to say that great work isn’t coming out on large presses, but it does mean that the big presses tend to be safer and are thinking more in terms of profit and marketability than ever before.

It’s no great secret that many amazing writers from all walks of life are publishing on university and indie presses where they have more freedom to express their originality and to break from the corporate norms, restrictions, censorship, and sales expectations. However, the obvious downside is that the mainstream might never become exposed to small press books for a variety of reasons, such as lack of advertising, P.R. and other resources; there are benefits to being part of the corporate machine, of course, and much of today’s best writing is relegated to the shadowy corners of the publishing world, despite its merit. But the small presses aren’t complaining. The New York establishment’s loss is often their gain.

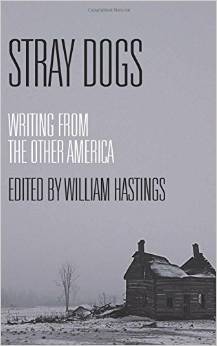

Recently, I was fortunate enough to be part of such a small press project I’m really proud of, with a group of writers I greatly admire. This anthology, Stray Dogs: Writing from the Other America, stands out because, from cover to cover, it offers up the sort of vigor from which great literature comes. Stray Dog contributors, from the relatively well-known to lesser-known, write with originality, passion, and audacity. It is literature as it should be: pure, vibrant, and unfiltered. The unifying factor of these well-written, albeit aesthetically distinct pieces, is their treatment of the down-trodden, the working-class, the underbelly of society, and they accomplish this in a raw, yet beautifully unique way. Not every reader shares the same aesthetic taste, but readers should understand that contemporary literature doesn’t necessarily always resemble the books that line the shelves of major corporate booksellers. Those who know literature well recognize that, historically speaking, not all great writing is cosmopolitan and safe, yet many contemporary readers and scholars fall for the corporate trap.

Recently, I was fortunate enough to be part of such a small press project I’m really proud of, with a group of writers I greatly admire. This anthology, Stray Dogs: Writing from the Other America, stands out because, from cover to cover, it offers up the sort of vigor from which great literature comes. Stray Dog contributors, from the relatively well-known to lesser-known, write with originality, passion, and audacity. It is literature as it should be: pure, vibrant, and unfiltered. The unifying factor of these well-written, albeit aesthetically distinct pieces, is their treatment of the down-trodden, the working-class, the underbelly of society, and they accomplish this in a raw, yet beautifully unique way. Not every reader shares the same aesthetic taste, but readers should understand that contemporary literature doesn’t necessarily always resemble the books that line the shelves of major corporate booksellers. Those who know literature well recognize that, historically speaking, not all great writing is cosmopolitan and safe, yet many contemporary readers and scholars fall for the corporate trap.

Last November I had the great pleasure of joining some of the other Stray Dog contributors on a panel for NoirCon in Philadelphia. When asked about the politics behind our work, I said that I wasn’t particularly political, but thinking back on it now, maybe I was wrong; how could the work of someone like me be anything but political? As Eric Miles Williamson, keynote speaker for the event and fellow anthology contributor remarked, the “Stray Dogs’” very lives are noir because of our experiences and our decision to tackle these often unpleasant topics in our respective writing. To the best of my knowledge, all of the contributors: Dickey Betts, Sherman Alexie, Willy Vlautin, Vicki Hendricks, Chris Hedges, Chris Offutt, Jason Isbell, Daniel Woodrell, Patrick Michael Finn, Steven Huff, Williamson, Ron Cooper, Esther G. Belin, Michael Gills, Larry Foundation, Mark Turcotte, and the editor, William Hastings, know quality, complexity, and authenticity quite well. Some have referred to our type of writing as “working-class noir,” “gutter poems,” or even “American Meta-realism.” My goal isn’t to label their work or my own, but I do see commonalities when I read these pieces side by side in the anthology, and the collective sensation from reading these works, although they vary stylistically as individual works, is that they do share many of the same nuances and the common “political” concerns I’ve mentioned, despite the authors’ differences in gender, culture, or geography.

What makes a collection like Stray Dogs: Writing from the Other America so unique and magnificent, though, is the way in which the “politics” are rendered, with such attention to beautiful aesthetics and a rich literary tradition; it’s not a collection of blatantly politicized writing, nor is it overtly didactic. What’s represented here is not simply another version of identity politics, but great writing that is, at its essence, a nefarious mosaic of the America that most people would rather ignore, delivered in beautiful, raw, aphoristic splendor. Artists, in general, tend to be determined people, but when folks from the working classes decide to make art their vocation, they realize there is no turning back. To me, Stray Dogs smells like a literary movement, and I believe there are many more “stray dogs” out there from all races, ethnicities and genders, who aspire to great art. If they are willing to tell their stories, describe where they’re truly from, some might view their art, as well as their very existence, as problematic and controversial, but the literary world will be all the more rich for their respective contributions. So if you’re looking for feel-good stories about the American dream, you might want to look elsewhere or just look away in denial; if you can handle the dark alleys, the seedy bars, the cheap whiskey and cigarette smoke, the domestic discord, and the cursing and gutter stench, why not grab a case or two of cheap beer and run awhile with the dogs?

Joseph D Haske

Joseph D. Haske is a writer, critic and scholar, whose debut novel, North Dixie Highway, was released in October 2013. His fiction appears in journals such as Boulevard, Fiction International, the Texas Review, the Four-Way Review, Pleiades, and in the Chicago Tribune‘s literary supplement, Printers Row. His poetry and fiction are also featured in various anthologies as well as in French, Romanian and Canadian publications. Haske edits various literary venues, including Sleipnir and American Book Review. He is professor of English at South Texas College.