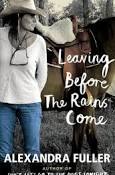

5/23/15 THE RAINS DOWN IN ZAMBIA

5/23/15 THE RAINS DOWN IN ZAMBIA. SONIA LINEBAUGH ON ALEXANDRA FULLER’S “LEAVING BEFORE THE RAINS COME

Alexandra Fuller moved to Wyoming two decades ago—but it’s her twenty years growing up in Zambia that inhabit her psyche and her writing. I know, I know, it’s my third post in a row about Africa. And about heartbreak. I’ve been plenty of other places, and heartbreak happens everywhere, but Africa keeps coming to me.

The book is titled Leaving Before the Rains Come, words the author’s father said about deciding to sell his farm beside the Zambesi River. It refers as well to the author’s anfractuous path to leaving her marriage.

The writing constantly circles the idea of identity. Fuller’s parents took her and her sister to South Africa when she was two. Over the next twenty years they lived there and in Rhodesia, which became Zimbabwe, and in Zambia. There were high times and low times, many farms, and the deaths of three younger siblings. Her mother went mad, but her dad stayed with her. Boring was the number one sin, according to him, the only unacceptable state of being. Alexandra never had to think about who she was.

But later, when she was a wife and a mother with three children, and she had no idea who she was, at a book reading in Dallas, someone asked, “Do you consider yourself an African?” No one questioned the black speakers, but they questioned her right to call herself African, as they always did. She longed to say yes as she usually did, to declare with confidence who she was, but for the first time, she didn’t know how to answer. At last she said, “Not anymore. Not especially.”

She had no idea who her husband Charlie was either, but he was not the man she had imagined she wanted. At age 22, she’d seen him as a man without her brokenness, a man who made a sanctuary and a living of the wild places, someone who would give her a life that would be good and ordinary and sane.

It turns out good and ordinary and sane bored her—though she never writes exactly that. With Charlie’s fledging safari business snared intractably in government red tape, and a new baby in the house, they gave up on their life on seven walled acres and headed for the USA. After trying Idaho, they moved to Wyoming which had loomed large in Charlie’s youth as a land of wildness and freedom, but a wife and baby changed his outlook. Wyoming was ripe for development and the real estate business was his way ahead. He fell back on the standards his wealthy Philadelphia family, putting financial security and its accoutrements first. And, like his family, he didn’t talk about unpleasant times. Rather, they did talk about them—a kidnapped child who was never recovered, fatal accidents, drunkenness—but in subdued language that Alexandra couldn’t understand. They were, perhaps, like her English relatives on her father’s side. Unlike the Africans who lived every day with the possibility of sudden death, “they couldn’t see their own oblivion coming.”

She was lost to herself in this new life, and Charlie was lost to her.

The memoir weaves the disappointment of a lusterless marriage with visits home to Zambia and riveting recollections of a crazy world of drunken adults, soldier saviors and molesters, malaria, civil war, charging elephants, ululating mothers on their way to little funerals.

The author tells of one tragedy after another with writing that sparkles with acerbic wit. At her wedding the food spoiled on its way to the farm, and they had to improvise with a whole steer and a whole pig roasted over an open fire in the garden. The bride had an attack of malaria. The choir from a nearby boarding school got uproariously drunk. Her sister wouldn’t act as maid of honor because she was afraid of spreading her own bad marriage luck. The Polish priest from the Catholic mission gave unasked for advice about marriage, “The first year is hard, and after that it gets worse.” His words proved true though it was more than a year before she realized it.

When the fault lines of the marriage are the topic, the heaviness is in the writing too. “I had no idea what okay might look like, because for reasons that long ago trickled out of my grasp, I had never fully, or even partially understood whole parts of our life.” The crash of the US real estate market accelerates the fall of the marriage. Charlie worried he’d have to sell the polo ponies. Alexandra’s reaction was, “Well, they should be worth a bit more than our souls were.” Alexandra had an affair. Charlie told her the marriage couldn’t afford to end.

She thought f the animals at the end of Africa’s dry season, on the move, despite seeming madness towards the water that is to come. The sensible thing was to hunker down, but that’s not what the animals did. That’s not what she would do.

Then there was an accident. Friends and family expected it would pull Charlie and Alexandra back together. But she didn’t agree. At the end of the dry season, she traveled back to Zambia. It was only for a visit. Her Dad said, talking about his plans for selling the farm, “You always think there will be more time and then suddenly there isn’t. You know how it is. You have to leave before the rains come, or it’s too late.”

Remember Toto’s popular song? “I bless the rains down in Africa…I seek to cure what’s deep inside, frightened of this thing that I’ve become…I bless the rains down in Africa.” It was written by a couple of young men who’d never been to Africa and recorded in 1982, the year Alexandra Fuller was twelve. People said the lyrics didn’t make sense. Others understood everything.

Sonia Linebaugh

Sonia L. Linebaugh is a freelance writer and artist. Her book At the Feet of Mother Meera: The Lessons of Silence goes straight to the heart of the Westerner’s dilemma: How can we live fully as both spiritual and material beings? Sonia has written three novels and numerous short stories. She’s a past president of Maryland Writers Association, and past editor of MWA’s Pen in Hand. Her recent artist’s book is “Where Did I Think I Was Going?,” a metaphorical journey in evocative images and text.