A Dialogue on Historical Fiction

9/13/2015 A Dialogue on Historical Fiction

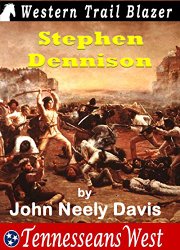

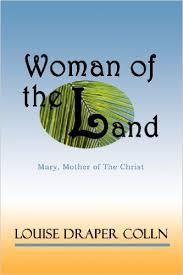

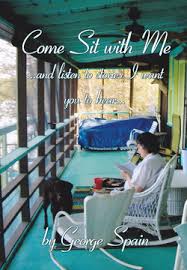

Three authors join me this month to discuss their thoughts on the genre of historical fiction. They are: Louise Colln, author of Woman of the Land: Mary, Mother of the Christ, and The Women of Rogers Street; George Spain, author of Lost Cove, Our People: Stories of the South, and The Last Giant, and Come Sit with Me…and Listen…; and John Neely Davis, author of The Sixth William, and Bear Shadow.

Michael: How would each of you define historical fiction?

George: I see historical fiction as the creation of a story set in the past with details of time and place, and with events and characters that intermingle realities with creations. The accuracy of sensory detail and of language puts “flesh on dry bones” and creates a sense of reality.

John: Sorry George, but in my opinion, there is no fiction, historical or otherwise. A writer of fiction

is a gatherer. This might be shocking to both writers and non-writers. Unless the writing is in either the genre of science fiction or fantasy, there is no fiction. At some point, somewhere in the past, a person has done exactly the same thing as your fictional character is doing. Maybe not a single character, but several people—maybe a hundred or a thousand people—have done, thought, acted or reacted exactly as your characters are doing now. You’ve heard about a trait or characteristic. Maybe you read something or shared a feeling. But whatever it is, it is in your subconscious. Who knows, maybe it is genetic memory?

is a gatherer. This might be shocking to both writers and non-writers. Unless the writing is in either the genre of science fiction or fantasy, there is no fiction. At some point, somewhere in the past, a person has done exactly the same thing as your fictional character is doing. Maybe not a single character, but several people—maybe a hundred or a thousand people—have done, thought, acted or reacted exactly as your characters are doing now. You’ve heard about a trait or characteristic. Maybe you read something or shared a feeling. But whatever it is, it is in your subconscious. Who knows, maybe it is genetic memory?

Historical fiction is simply set in the past. The past can be something that happened in the last minute or centuries ago.

Louise: John, let’s not make it so complicated. Historical fiction is simply any created story set in a past era.

Louise: John, let’s not make it so complicated. Historical fiction is simply any created story set in a past era.

Michael: I like to stay in the familiar. My stories take place during historical times and events that I lived through. Things like the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the troubles in Northern Ireland. I saw the events played out on the evening news and the daily newspapers. It gives me a chance to revisit those events by putting my fictional characters on the periphery of the action.

What about you all? How do you determine the period you will write in?

John: I feel comfortable going from today back to the 1830s with my writing. I had a cousin,  Stephen Dennison, die at the Alamo in 1836. My grandfather’s mother knew Dennison’s mother. My fore-kin (I made that word up because I needed it) came though the Cumberland Gap before that. Those stories have been passed down. I can barely loosen my imagination, and people of that period come to life.

Stephen Dennison, die at the Alamo in 1836. My grandfather’s mother knew Dennison’s mother. My fore-kin (I made that word up because I needed it) came though the Cumberland Gap before that. Those stories have been passed down. I can barely loosen my imagination, and people of that period come to life.

George: Like you John, my stories are set in Tennessee between the late 1770s and 1950s. And there is the family connection. The stories often rise from events and people of my wife’s family or of mine. For the most part I’m familiar with the locations where the stories occur.

Michael: Louise, for Woman of the Land, you selected a time frame that was 2,000 years ago. What drove that decision and what did you do for research?

Louise: I get the “why” question a lot and I can’t answer it. I wanted to make Mary a natural woman in her world responding to the sometimes unnatural things happening in it and in order to do that I had to create that world and move into it with her when I wrote. I absorbed maps, biblical, historical, mythical, word-of-mouth, beliefs, conflicting beliefs and myths and then had to decide which made a smooth flow of incidents.

in her world responding to the sometimes unnatural things happening in it and in order to do that I had to create that world and move into it with her when I wrote. I absorbed maps, biblical, historical, mythical, word-of-mouth, beliefs, conflicting beliefs and myths and then had to decide which made a smooth flow of incidents.

For instance the star, according to Copernicus it wasn’t one star that moved before the kings but a triple conjunction of three planets, which the astrologers believed were connected with Israel. The dates of these and the use of tents for winter cover allowed the birth to be in winter. I followed this procedure through the book, which is one reason it took so long to write it.

George: Where do you get your ideas for stories?

Louise: They come from the periods and events and people I find interesting.

Michael: Story ideas are as tangible as smoke, and if you get a whiff of that smoke, then you have something to work with. My stories are character driven, so everything starts with them. As the story progresses I research events of the time to see if my character has a skillset or personality to get drawn into the historical moment.

Michael: George, are all of the characters in your novel real people?

George: While many of my characters are based on real people I expand on them in order to add spice and to take the story where I want it to go. I have a rule of thumb: Never let a fact stand in the way of a good story.

Michael: John, your award winning novel, Bear Shadow, takes place in rural Tennessee at the turn of the 20th century. What did you do to research the period? And at the end of the novel there was a very realistic obituary. Was that character real?

John: I was born in 1938. The turn of the century was not too old at that time. My grandfather was born just after the Civil War. We sat on the front porch swing during long summer night. Nearing ninety, his memory was encyclopedic.

front porch swing during long summer night. Nearing ninety, his memory was encyclopedic.

I was kinda proud of the obituary. I researched Australian obits and could not find anything I felt comfortable with. Suzanne Sparks of the Williamson County Library and I were finishing Bear Shadow for the final copy. Something seemed lacking. I wrote the obit, she typed it. We mangled the paper and fiddled with the Xerox to produce a rugged reproduction, which is the final page of the book.

George: What are your main sources for research?

Louise: Going to the setting if possible. I’ve visited most of the Trail Of Tears and spent a cold misty morning on the Culloden battlefield. For two books on the Civil War in the South I used a valley in North Carolina and studied the many available books on conditions during and immediately after the war. I like the little details in old books that aren’t found on the Internet though I do use the Internet.

Louise: Going to the setting if possible. I’ve visited most of the Trail Of Tears and spent a cold misty morning on the Culloden battlefield. For two books on the Civil War in the South I used a valley in North Carolina and studied the many available books on conditions during and immediately after the war. I like the little details in old books that aren’t found on the Internet though I do use the Internet.

Michael: Google. Also, if I can, I like to visit the area and get a sense of the people and the geography. I went to Baltimore’s Little Italy, Fells Point, and Fort McHenry before writing those scenes for Capricorn.

Louise: Mike, in Aquarius Falling you used Maryland’s Ocean City as the setting. That town went from village to roaring city in a few decades. How did you make sure your characters didn’t connect to something that wasn’t there in the sixties?

Michael: Well, like John’s grandfather, on some things, I too have an encyclopedic memory. There are certain iconic places that simply cannot be erased from my mind, and I pretty much stuck to those. Where possible I used the original names, such as the restaurants and boardwalk french fry locations. However, in locations where illegal acts took place, I created fictional names. Sort of protecting the innocent.

John: Mike, automobiles are an important facet in your writing. Have you always been a car enthusiast and what was your favorite ride?

Michael: Yeah, I guess I was lucky enough to come of age in the 50’s and 60’s when cars were king. They were all unique in their design. A Chevy didn’t look like a Pontiac, and a Ford didn’t look like a Mercury. Every year the new model was introduced and it looked like a completely different car from the previous year. The design was a secret until early September, and then people went to the dealer’s showroom in droves just to look at it. It was like a movie premier in Hollywood. It was a big, big, deal. Crazy.

As for my favorite car…Tom Delaney’s yellow Jaguar XKE in Capricorn’s Collapse. Many believe, (and I agree with them) that the XKE is the best-looking production car ever made. But thanks to Lucas Electronics the car was a maintenance nightmare. Owning an XKE was like marrying a psychotic beauty queen, great to be seen with in public, but hell to pay when alone at night. There is a joke that says, Lucas Electronics motto is “Get home before dark.”

Michael: In my novels actual historical characters, such as Richard Nixon, serve as background. They never actually enter the story to interact with my fictional characters. What about you all – do you use actual historical characters in your novels, or only fictional characters?

Louise: Obviously, Mary, the mother of Jesus, and all the important characters in Woman of the Land were real historical figures and play key parts in the story. But except for that story, all my characters are fictional. Even details of their personality are totally out of my head though some of them may be from subconscious memories.

George: Like you, Mike, I will include a “historical character” as a reference point to the event or location. Some stories are created entirely from fictional characters.

John: I’ve used more than a few real characters in my fiction. Obviously, when I wrote the novella about Dennison at the Alamo, I had to use real characters. Some of the less famous required considerable research. You don’t have to research Davy Crockett, because there is nothing you could add to the real character that you don’t already know.

Most of the Bear Shadow characters were thinly veiled. My mother, an aunt, and a son-in-law’s mother were the basis of Mrs. Doran. The accounting of Asia Davies, the itinerant preacher is my great-great-grandfather. I’ve known bullies all my life; Eli was one. Cuva and her daughter, Amelia, combined every dark skinned, dark haired, good-looking woman I’ve ever known.

George: What guides you in bringing your characters alive?

Louise: The characters do. They sometimes have conversations or actions that surprise me and they change during the story.

Michael: I agree with Louise. But sometimes research will inspire an idea. While writing Capricorn’s Collapse, Misty Vail (an important character) reminded me that she was a Jew, and that I need to get her reaction to the terrorist actions in the 1972 Munich Olympic Games.

Michael: Have you ever received critical comments about how you portrayed the period or a real character?

John: It always surprises me the kick readers get out of seeing their name in fiction. Especially if it is a heroic character. An elementary school friend has bugged me for years to use her name in a book. “But,” she said, “It must be a woman of high morals.” In a Western trilogy I’m writing, I’ve used her name, Angalee. But the character does not fit her name. So, I’m changing the name of the tarnished woman to Lorelei. I’ll use Angalee later. So, I am dodging that bullet. Pre-empting, you might say.

John: It always surprises me the kick readers get out of seeing their name in fiction. Especially if it is a heroic character. An elementary school friend has bugged me for years to use her name in a book. “But,” she said, “It must be a woman of high morals.” In a Western trilogy I’m writing, I’ve used her name, Angalee. But the character does not fit her name. So, I’m changing the name of the tarnished woman to Lorelei. I’ll use Angalee later. So, I am dodging that bullet. Pre-empting, you might say.

A few years ago, a woman from Thailand wrote me. She named her first son Creighton after the protagonist in The Sixth William. Go figure.

Michael: That’s funny. Along a similar line I understand that my children and my ex-wife have spent a considerable amount of time trying to figure out who “the real Wendy” is. (Tom Delaney’s love interest in Aquarius Falling.)

Louise: I’ve had many on Woman of the Land express both approval and disapproval on concept and details of both the story and characters.

George: I’ve had many who have known me for years that are unable to separate the real from the fictional.

John: And that’s as it should be George.

George: What about dialect? Do you use it? If so, why, or if not why?

Michael: Coming from you that’s like a trick question. You use it a lot and to great effectiveness. You’re very good at it, George. I hate to use it for two reasons. It’s hard to get it right, and you have be consistent with it. I only use it if it’s important to portraying something about the character.

Louise: Sparingly. Just enough to indicate the period and setting I am in.

George: How much sensory detail do you use?

Louise: It depends on the part of the story I’m writing. Sometimes I’ll do just enough to let the reader know where the character is if I’m moving the action along, or especially if the setting is a part of the action.

Michael: Yes, it can make a scene more realistic. An example was a bakery in the Fells Point area. When they are baking bread you can smell the aroma for blocks.

John: George: If you could leave only one piece of your writings for your descendants, what would it be?

George: Lost Cove.

George: Lost Cove.

Michael: Well, that pretty much covers our subject for today. A big thank you, Louise Colln, George Spain, and John Neely Davis.

Michael J. Tucker

Growing up in the cold northern climate of Pittsburgh, PA, and an only child, Mike was often trapped indoors and left to his own devices, where he would create space ships out of cardboard boxes, convert his mother’s ironing board into a horse and put on his Sunday suit and tie and his father’s fedora and become a newspaper reporter or police detective. This experience left him with an unlimited imagination and the ability to write electrifying short stories and novels.

Mike is the author of two critically acclaimed novels, Aquarius Falling and Capricorn’s Collapse. He has also published a collection of short stories entitled, The New Neighbor, and a poetry collection; Your Voice Spoke To My Ear. His poem, The Coyote’s Den, was included in the Civil War Anthology, Filtered Through Time.

He is a judge for the Janice Keck Literary Award, and the moderator of the Williamson County Library Writers’ Critique Group.

Reviewers of Mike’s novels have compared his writing to: Thomas Wolfe’s I Am Charlotte Simmons, and J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. Albert Beckus, Professor Emeritus of Literature at Austin Peay University recently wrote of his novels: “They move naturalistically in the American literary tradition of Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, but with a twist…as found in The Great Gatsby.”

- Web |

- More Posts(22)