Another Look at Catcher in the Rye

2/7/16 — Another Look at The Catcher in the Rye

2/7/16 — Another Look at The Catcher in the Rye

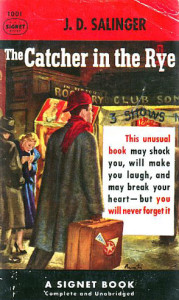

I don’t recall how old I was when I first read J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye–fourteen or fifteen, perhaps. Everyone seemed to be reading it then, and afterward, everyone seemed to adapt Salinger’s writing style. English classes became tedious as student after student read his “original” composition in an imitation of Holden Caulfield’s voice.

All of us wanted to be Holden Caulfield. We wanted to travel through New York as he did — alone, with money in our pockets, and at all hours. We wanted to read the books he liked, drink scotch, and call out the phonies. We liked that he was a straight talker, glib and slangy, a no-holds-barred kind of guy, our generation’s John Wayne.

That was the Holden Caulfield of my childhood. Some fifty years later, I’ve revisited The Catcher in the Rye, and Holden looks very different to me. This book about an adolescent so loved by adolescents of the 1960s, is, I think, more complicated than it first appears. The writing is so pitch perfect that it can seduce readers into admiring Holden. Ensnared by his tone, they ignore the reality of what he is saying.

But as early as the first page, Salinger warns the reader that Holden, the narrator, is not to be trusted: “I’m not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything.” He’s going to be selective in what he says, and if that’s not enough of a hint at his duplicity, in chapter three he says, “I’m the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life. It’s awful.” We don’t have a straight-talking narrator at all; we’re in the hands of a liar.

We’re also in the hands of a masterful author. The novel is like a concerto with expositions, developments, and recapitulations. We readers don’t have to watch out just for deceit and omissions but also for twists and turns as Salinger guides us through Holden’s days and his mind.

Even his reading gives us clues as to how he feels. Out of Africa, The Return of the Native, and Of Human Bondage concern people who are outsiders. In Holden’s favorite Ring Lardner story, “There Are Smiles,” the narrator becomes a changed person by falling in love with a carefree young woman who dies in a car accident. A married man, he has to keep this sorrow to himself.

Holden admits to being immature and dreads becoming a phony adult. He wants to be left alone, but seeks companionship. He sees himself as a savior to young kids — the catcher in the rye — but doesn’t know how to save himself. Former teachers, classmates, and friends all disappoint him. Even his father will kill him, his sister tells him.

Holden misses Allie, the brother he lost to leukemia, and as the book ends, we read that Holden’s missing everyone.

This cool, smart character of my youth looks to me now like a scared, confused, lost, but still smart, kid. I wouldn’t be him for anything and wouldn’t wish his unhappiness on anyone. What I do wish is that everyone reads, or rereads, Catcher in the Rye.

Janet Willen

Janet Willen is author of Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery (2015) and Five Thousand Years of Slavery (2011), written with Marjorie Gann and published by Tundra Books. Publishers Weekly called Speak a Word for Freedom an “engrossing study of female abolitionists from the 18th century to the present day” and gave the book a starred review. Five Thousand Years of Slavery was named a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association and a Silver Winner in young adult nonfiction of ForeWord Reviews, and it received a starred review from School Library Journal. A writer and editor for more than thirty years, Janet has written many magazine articles and has edited books for elementary school children as well as academic texts and a remedial writing curriculum for postsecondary students. Janet lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.