3/10/2016. BOOK REVIEW—MY BRILLIANT FRIEND BY ELENA FERRANTE

3/10/2016. BOOK REVIEW—MY BRILLIANT FRIEND BY ELENA FERRANTE

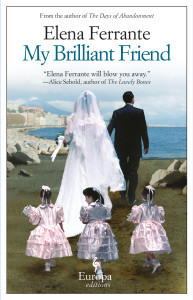

When I learned that Elena Ferrante (a pen name) refused to reveal any information about herself because she believed her novels should stand on their own, I wanted to applaud. As Mark Willen explained in his post on Late Last Night Books in July, Ferrante believes that “books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they won’t.” What a refreshing idea. I couldn’t wait to read My Brilliant Friend, the first novel in Ferrante’s Neapolitan tetralogy. Here’s what I found: the novel definitely stands on its own, but it’s almost as difficult to talk about as its enigmatic author.

information about herself because she believed her novels should stand on their own, I wanted to applaud. As Mark Willen explained in his post on Late Last Night Books in July, Ferrante believes that “books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they won’t.” What a refreshing idea. I couldn’t wait to read My Brilliant Friend, the first novel in Ferrante’s Neapolitan tetralogy. Here’s what I found: the novel definitely stands on its own, but it’s almost as difficult to talk about as its enigmatic author.

My Brilliant Friend is an intricate literary novel. As in all good literary novels, it has a plot, but the plot is secondary to the ideas explored by the author. The writing is dense, complex, and not always easy to read. It requires concentration. But the skill with which Ferrante weaves the ideas in with the characters is amazing to behold. The characters are like little time bombs of humanity waiting to explode. Their fiery personalities are constantly igniting and cooling in regard to each other. Their family relationships are significant, so to help the reader understand the families and the characters with their many nicknames, the novel includes an index of characters, a nearly indispensable tool.

I think the best—maybe the only—way to try to convey a little of the essence of My Brilliant Friend, is to talk about some of the novel’s ideas.

The most prominent idea, the one most talked about in regard to the entire tetralogy, is the evolution of a friendship. In this first book of the series, two girls move together through childhood and adolescence. Elena, the narrator, initially sees the other girl, Lila, as her elementary school rival to be the smartest student in the class. She is also attracted to Lila because Lila is daring and not afraid to misbehave. The first gesture of friendship Lila extends to Elena is to lead her to the home of a frightening man in their neighborhood after she has dropped Elena’s doll through a grate into his cellar.

Eventually Elena comes to think that only she and Lila together can seize life and give it meaning. She begins to define herself in terms of Lila. The situation is exacerbated when a young friend who asks her to marry him when they grow up admits later he asked her only because he wanted to be part of the relationship between Lila and her. Elena begins to model herself after Lila. “I put myself in her place,” Elena says. “Or rather, I had made a place for her in me.”

As the two become teenagers, Elena sees the relationship as more divergent than convergent. Not that they are any less close, but when one is happy, the other must be sad. When one is beautiful, the other must be ugly. During a summer spent with her teacher’s cousin at the shore, Elena begins to see herself as prettier than Lila, but upon her return, as events in Lila’s life begin to right themselves, Elena says “Satisfaction had magnified her beauty, while I . . . was growing ugly again.”

A second idea that is almost as prominent as the friendship is the need to escape the past. Initially, Elena is most concerned with escaping the poverty and violence of the section of Naples where she and Lila live. She realizes early that “in the neighborhood terrible things could happen, fathers and sons often came to blows.” Even Lila can be violent. When a neighborhood brute manhandles Elena, Lila pulls out a knife she took from her father’s shoemaker shop, shoves the brute against a car, and presses the knife against his throat. “Touch her again and I’ll show you what happens,” she says.

As the girls grow older, the neighborhood violence becomes a more internal burden. When a friend tells them about the evil in the outside world—Fascism, Nazism, and World War II, which was only a few years earlier—Lila becomes obsessed with the idea that “there are no gestures, words, or sighs that do not contain the sum of all the crimes that human beings have committed and commit.” Elena hopes that since she will leave Lila and most of the other neighborhood children to go to high school, she will detach herself from “the misdeeds and compliances and cowardly acts of the people we knew, whom we loved, whom we carried . . . in our blood.”

Related to the idea of escaping the real self is Lila’s phenomenon of dissolving margins. Although she doesn’t have a name for the phenomenon until she is older, she first sees the outlines of people and things dissolve and disappear when she is a child. She describes the sensation as “the impression that something absolutely material, which had been present around her and around everybody and everything forever, but imperceptible, was breaking down the outlines of persons and things and revealing itself.”

In this first encounter, she seems to see her brother for the first time as he really is: “a squat animal form, thickset, the loudest, the fiercest, the greediest, the meanest.” Years later, she sees it happen to her brother again. “She now had a brother without boundaries, from whom something irreparable might emerge.”

Ferrante is honest in her ideas, unforgiving in the details. Variety recently reported that Italian film and TV company Wildside is planning an international TV series based on the four Neapolitan novels. I hope the series is shown in the United States because I will be eager to see how Ferrante’s ideas translate to the screen.

Sally Whitney

Sally Whitney is the author of When Enemies Offend Thee and Surface and Shadow, available now from Pen-L Publishing, Amazon.com, and Barnesandnoble.com. When Enemies Offend Thee follows a sexual-assault victim who vows to get even on her own when her lack of evidence prevents police from charging the man who attacked her. Surface and Shadow is the story of a woman who risks her marriage and her husband’s career to find out what really happened in a wealthy man’s suspicious death.

Sally’s short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017, Main Street Rag, Kansas City Voices, Uncertain Promise, Voices from the Porch, New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers and Grow Old Along With Me—The Best Is Yet to Be, among others. The audio version of Grow Old Along With Me was a Grammy Award finalist in the Spoken Word or Nonmusical Album category. Sally’s stories have also been recognized as a finalist in The Ledge Fiction Competition and semi-finalists in the Syndicated Fiction Project and the Salem College National Literary Awards competition.

- Web |

- More Posts(67)