5/10/2016. INTERVIEW WITH JAMES SCOTT, AUTHOR OF THE KEPT

5/10/2016. INTERVIEW WITH JAMES SCOTT, AUTHOR OF THE KEPT

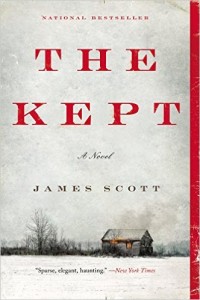

Only a brave author would create his debut novel with characters who are different from him in almost every way. James Scott, author of The Kept, took on that challenge and compounded it with a harsh setting and even harsher themes. But as I said in my review of The Kept last month, Scott gives his characters multi-dimensional personalities that shine against the turmoil of the story. I was eager to ask him how he combined those elements so well. He shares some of his thoughts on process and inspiration below.

are different from him in almost every way. James Scott, author of The Kept, took on that challenge and compounded it with a harsh setting and even harsher themes. But as I said in my review of The Kept last month, Scott gives his characters multi-dimensional personalities that shine against the turmoil of the story. I was eager to ask him how he combined those elements so well. He shares some of his thoughts on process and inspiration below.

Scott’s previous work has been short listed for the Pushcart Prize and nominated for the Best New American Voices. He’s received awards from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the New York State Summer Writers Institute, the Millay Colony, the Saint Botolph Club, the Tin House Summer Writer’s Conference, Yaddo, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.

SW. The harsh setting in The Kept is as dominant as the characters. Did the idea for this story begin with the setting or with a character? How do ideas for your stories usually begin?

JS. Neither, actually. Or a little bit of both? The story began with the image of Caleb wiping the snow from Emma’s face. I had no ideas about character or setting at that point. Besides boy and girl and snow. Those things came into focus as time went on, though snow limits the setting and I decided the boy and girl were brother and sister early on.

Stories begin in all sorts of ways for me. Setting is rarely where I begin, I guess. Sometimes it’s an image, or a sound (someone talking, usually), or a feeling I’m going for that starts the ball rolling, so to speak. With short stories, the first line sometimes comes to me first, and I’ll jot it down somewhere and find it later and realize that I have some more information to fill in around it, or below it, more specifically.

SW. Since The Kept is not a Young Adult novel, did you have any apprehension about having an adolescent as one of the main characters? What was the hardest part of creating Caleb as a twelve-year-old?

JS. Nope. None at all. I would have had reservations, perhaps, if he was the only character, but that was never really a thought.

The most difficult part of creating Caleb was setting myself back to zero (I was nothing like Caleb as a kid) and imagining what life would look like to someone who’s never left his isolated farm. That took some doing.

SW. Your other main character, Elspeth, is a woman. As a man, how did you prepare for exploring the mind of a woman?

JS. I don’t mean this in an ultra-PC kind of way, but I don’t really think of gender in those absolutes. I try to think of all my characters not as belonging to this group or that group, but as individuals. Another example is sometimes someone will tell me a character is “good” or “evil,” and I don’t really think of people (or characters) in those binary terms, either. I think one can sometimes end up with flat characters in that way.

Now, it does so happen that Elspeth is a mother, and that was something that I had to consider and nail down in terms of her thoughts on what it meant to be a mother and what it meant to have children. That’s what I was most concerned about getting right.

SW. Caleb and Elspeth are complex characters that reflect the good and bad in all of us. As a writer, how do you create a character who has serious flaws, but with whom readers will still empathize?

JS. Thank you! I hope so. I think that the complexity is what leads to the empathy. If characters feel real, and their internal logic makes sense, then you’ll go with them wherever they go. You don’t have to agree with it, and you don’t have to like it, but you have to understand why they’d be compelled to do it. I think the other thing is that when the characters do things that are wrong, they usually recognize that they’re wrong. Hence the opening line of the book.

SW. Elspeth and Caleb do not have a typical mother-son relationship. How did you develop their relationship? When you started writing the novel, did you know what their relationship would be like and where it would go?

JS. I had a pretty clear vision for how things would go between them, and I wrote simple sentences on index cards to keep their dynamics in mind as I went along. They changed, but I kept them above my desk and would glance at them as reminders. The important thing between them, as between any two characters, is the push and pull of their affections, their power structures, and their understanding of one another. It’s a lot to keep straight! Being aware of the bubble a character lives in, and the limitations of what they do and do not know, is critical for creating tension.

SW. What is the significance of the novel’s title for you?

JS. I think all good titles point to more than one thing in the book, so that each time you stop for the day (or night) and you close that cover, and see that title, it means something slightly different. So depending on where you are in the book, the notion of things being kept, whether they’re secrets or objects or people, is (hopefully) ever-changing. I feel the same way about book covers, too, actually. Those things—titles, covers—should be as alive as possible.

SW. Since The Kept is a historical novel, how much research did you do and how did you do it?

SW. Since The Kept is a historical novel, how much research did you do and how did you do it?

JS. Oh, boy. Tons of research. The biggest thing I did was buy a Sears catalogue from a couple of years before the events in the book. I’d heard the amazing Tom Franklin talk about how he’d done this for Hell at the Breech and it made sense to me. For the ice cutting, I watched people do it at a winter festival in Wisconsin (I think?) online. The hardest thing was finding the right information about being a midwife. I read tons of books and thesis projects and dissertations, but I eventually spoke with a midwife and she cleared things up for me, and read the pertinent sections. That was amazing, and a good lesson to me.

SW. Could the story of The Kept be set in contemporary times? Why was it important to you to set it in the nineteenth century?

JS. No, I don’t think so. The facts of this event would, even only a few years later, mean that at some point, the media would become involved. The concept of the story being “A STORY” wasn’t something I was interested in. This era (1897 specifically) is on the cusp of the entire world changing with ever-increasing speed. It’s the pause at the top of the roller coaster. I like those moments, if you can pinpoint them. (Though I do not like roller coasters.) I’d say most of those advances are for the better (our lifespans have almost doubled for example), but the world is a noisier, busier, more populous place, and there’s something about the quiet before the storm that made this world and these characters make more sense.

SW. What do you hope readers remember about The Kept?

JS. That’s a good question, and something I’ve never really thought about. I think that if the characters stay with a reader, and the emotions of the story linger, then you’ve done about the best you can do as a writer.

SW. As a reader, what makes a novel memorable for you?

JS. What I described above. If I shut a book, and can immediately forget it, even if I liked it while it was happening, then that’s no good. That’s not what I read for. I’ve read many, many books that are enjoyable but once the last page is turned, they’re already gone. But if the characters feel real, and I’ve spent a chunk of time with them, and I understand their hearts and their heads, then I’ll remember that book for a long, long while.

Sally Whitney

Sally Whitney is the author of When Enemies Offend Thee and Surface and Shadow, available now from Pen-L Publishing, Amazon.com, and Barnesandnoble.com. When Enemies Offend Thee follows a sexual-assault victim who vows to get even on her own when her lack of evidence prevents police from charging the man who attacked her. Surface and Shadow is the story of a woman who risks her marriage and her husband’s career to find out what really happened in a wealthy man’s suspicious death.

Sally’s short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017, Main Street Rag, Kansas City Voices, Uncertain Promise, Voices from the Porch, New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers and Grow Old Along With Me—The Best Is Yet to Be, among others. The audio version of Grow Old Along With Me was a Grammy Award finalist in the Spoken Word or Nonmusical Album category. Sally’s stories have also been recognized as a finalist in The Ledge Fiction Competition and semi-finalists in the Syndicated Fiction Project and the Salem College National Literary Awards competition.

- Web |

- More Posts(67)