Goodies From My Book Groups

A friend of mine was in four book groups for many years. She couldn’t help herself. Whenever she heard about one, she thought she’d give it a try and quickly found herself hooked.

I’m now in three book groups, so I understand. One is with friends, another is at synagogue, and the third is at a home for seniors. Each group has its own personality, and I wonder how I ever managed with only one.

Without these groups, I’d have missed many a good read and discussion. They introduced me to Harriet Scott Chessman, Howard Norman, and so many more.

The three groups look for a meeting of the minds in choosing their books. Members of the synagogue group meet once a year to solicit participants’ recommendations before choosing the year’s list. At the senior home, I’m the facilitator and I tend to choose because of restrictions on size, the need for large-print editions, and the complexity of buying the book for everyone in time for them to read it.

The method I most like is the one my friends group uses. We have no restrictions except that the library must have enough copies so that no one will be obligated to buy the book. Each month one member is responsible for narrowing the choice. That person sends four recommendations with short descriptions of the books to the other members. Then, after we’ve discussed the current month’s book, we review the choices and make our pick for the next month. That way we share responsibility for the final choice, so no one has to apologize if we read a dud.

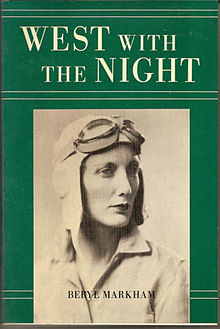

The tables were turned with West with the Night, Beryl Markham’s memoir of her life in British East Africa—from her childhood, through her years as a racehorse trainer and pilot, to her triumph in 1936, when, at age 34, she became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic from east to west. My friends considered the book disjointed but I loved it from the first paragraph:

The tables were turned with West with the Night, Beryl Markham’s memoir of her life in British East Africa—from her childhood, through her years as a racehorse trainer and pilot, to her triumph in 1936, when, at age 34, she became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic from east to west. My friends considered the book disjointed but I loved it from the first paragraph:

“How is it possible to bring order out of memory? I should like to begin at the beginning, patiently, like a weaver at the loom. I should like to say, ‘This is the place to start; there can be no other.’”

Even the realization that it may have been ghost-written by her third husband, Raoul Schumacher, did not diminish the beauty of the book for me. Whether it’s Schumacher’s biography or Markham’s autobiography, it’s a thoughtful and poetic book about an adventurous life. Or so it seems to me.

My book group is quite good at disagreeing without being disagreeable, to paraphrase another memoirist, Barack Obama.

Men are in only one of my book groups, the one at the synagogue. Perhaps book groups’ popularity reflects their history. American book groups may have had their origin in women’s salons in 18th-century England, Nathan Heller says in the Slate.com article “Book Clubs in America: Why Do We Love Them?” Back then, when women had few options for gaining an education, these literary ladies—the bluestockings—invited learned men to lecture them at their salons. These early efforts at self-education have evolved into today’s book clubs, Heller writes.

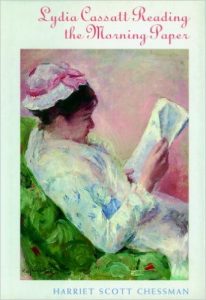

They’re certainly educating me. I hadn’t heard of Harriet Scott Chessman until her novel, Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper, showed up on a book group list. The book imagines the life of Mary Cassatt’s sister, Lydia, a woman most readers know only from the artist’s paintings, like “The Reader” and “Woman with a Cup of Tea.” Chessman uses five paintings, one for each chapter, to tell a mostly fictitious story of the sister who suffered from Bright’s disease for years before dying in 1882.

They’re certainly educating me. I hadn’t heard of Harriet Scott Chessman until her novel, Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper, showed up on a book group list. The book imagines the life of Mary Cassatt’s sister, Lydia, a woman most readers know only from the artist’s paintings, like “The Reader” and “Woman with a Cup of Tea.” Chessman uses five paintings, one for each chapter, to tell a mostly fictitious story of the sister who suffered from Bright’s disease for years before dying in 1882.

Though Lydia in the novel considers herself “plain as a loaf of bread,” we readers know from having seen her in paintings that Mary saw her differently, and Chessman shows us that three-dimensional woman. We read that she confides to Mary’s friend Edgar Degas, a man she dislikes, about her impending death and says, “I have nothing to leave behind.” But then, in a last letter to Mary, she writes about how she will dissolve in death and how Mary will think she will dissolve too. She continues, “You will remember me because you caught my soul in paint.”

And as we read, we can see her soul, in the writing and in the color reproductions of five paintings in the book that enhance the storytelling. Chessman’s writing is so effective and so true to the period that she had me see more deeply into Cassatt’s paintings and appreciating these works that I always more than ever before.

Paintings also have a place in The Bird Artist by Howard Norman, another book I encountered in a book group. Fabian Vas, the novel’s narrator, is a young man who paints birds in his hometown of Witless Bay, Newfoundland, in the early 1900s. He tells us this in the first paragraph of the book, when he also confesses to the murder of the lighthouse keeper, Botho August. Quickly readers begin to learn about the young boy who later takes someone’s life. With a librarian they pore over an artist’s hand-colored engravings of flowers, seeds, wild animals, and especially birds. She says to him:

“To you, Fabian, I imagine this work is as important as Leonardo Da Vinci’s.”

“Who’s Leonardo Da Vinci?”

“A great genius.”

“Did he paint birds?”

“Truth be told, I don’t know. He never painted them in Newfoundland.”

Fabian was a young boy, and his ignorance is not surprising, but the conversation underlines that they lived in a small, remote place. The book shows the evolution of the youngster, with his naïveté but also yearnings and the tensions in the small town. The New York Times book reviewer Michiko Kakutani described The Bird Artist as “part allegory, part coming-of-age story, and part murder melodrama.” That’s true, but I’d add that it’s also a book of place, of time, of humor, and of deep sensitivity.

I’ve gone on to read many of Howard Norman’s books and think they should be on every readers must-read list.

I can’t wait to see what my groups have in store for me next.

Janet Willen

Janet Willen is author of Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery (2015) and Five Thousand Years of Slavery (2011), written with Marjorie Gann and published by Tundra Books. Publishers Weekly called Speak a Word for Freedom an “engrossing study of female abolitionists from the 18th century to the present day” and gave the book a starred review. Five Thousand Years of Slavery was named a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association and a Silver Winner in young adult nonfiction of ForeWord Reviews, and it received a starred review from School Library Journal. A writer and editor for more than thirty years, Janet has written many magazine articles and has edited books for elementary school children as well as academic texts and a remedial writing curriculum for postsecondary students. Janet lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.