What Writers Can Learn from Tolstoy’s Novellas

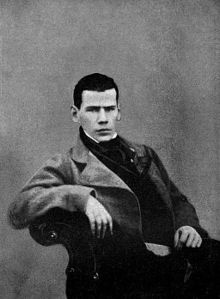

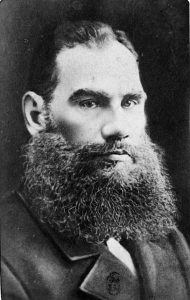

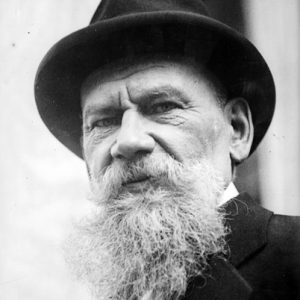

I’m shocked when I read lists of favorite novels and see that most, and sometimes all, are American. There may be a leavening of British authors too; that’s something. Still, I think, haven’t you read the Russians or the Germans? You really think Toni Morrison or Jonathan Safran-Foer are better than Tolstoy or Musil? Anglo-Saxon culture is lamentably insular, and American culture is not merely insular but downright provincial these days. The greatest weakness of the writing done by creative writing students—graduates as well as undergraduates—is that it’s so rarely informed by wide reading. And however unfashionable it may be, my remedy is to send them to the canon. Not “back to the canon”, sadly, because most of them aren’t familiar with it in the first place. And you can’t do better than start with a Dead White Male who was also (oh, unpardonable elitism!) an aristocrat, Count Leo Tolstoy.

I’m shocked when I read lists of favorite novels and see that most, and sometimes all, are American. There may be a leavening of British authors too; that’s something. Still, I think, haven’t you read the Russians or the Germans? You really think Toni Morrison or Jonathan Safran-Foer are better than Tolstoy or Musil? Anglo-Saxon culture is lamentably insular, and American culture is not merely insular but downright provincial these days. The greatest weakness of the writing done by creative writing students—graduates as well as undergraduates—is that it’s so rarely informed by wide reading. And however unfashionable it may be, my remedy is to send them to the canon. Not “back to the canon”, sadly, because most of them aren’t familiar with it in the first place. And you can’t do better than start with a Dead White Male who was also (oh, unpardonable elitism!) an aristocrat, Count Leo Tolstoy.

This semester I’m teaching a course on the novella, and the syllabus is not all Dead White Males—it includes Tolstoy, Chekhov, Mann, García Márquez and Kawabata—but it’s entirely un-Anglo-Saxon and I make no apologies for that. (And they are all dead males. I couldn’t find any women writers of that stature at the novella length. No, not even Alice Munro. Only Muriel Spark gave me pause.) The Tolstoy selections are all from The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories, and they’re all masterpieces. A lot of people are put off by the length of War and Peace and Anna Karenina, but Tolstoy could be very succinct indeed, as these selections show. The Death of Ivan Ilyich covers, in just over fifty pages, what most novelists could not pull off in a whole novel: the entire life of a man. Admittedly he’s a mediocrity, and his life is not very interesting—so already Tolstoy has broken one of the cardinal “rules” of writing, always to have a remarkable person as a protagonist—but instead of boring us with the details, he sweeps through decades, summarizing (the so-called “broad brushstrokes”) and then captivates the reader with the sudden onset of the protagonist’s illness and his realization that he has lived his life unwisely. The death itself, which is foreshadowed in the very first pages, with lots of black humour, as Ilyich’s friends, colleagues and family are almost all unaffected by his death except insofar as it might affect them, is rendered with a complete absence of sentimentality, and yet is moving. I pair this novella with Master and Man, for its similar themes: like Ilyich, Vassily Andreich is a shallow materialist, going to his death. He also has an epiphany as he dies that redeems his life. This may sound Disneyfied, summarized as briefly as this, but in fact it isn’t; Tolstoy writes of spiritual experience as well as anyone, and you don’t have to be a Christian to appreciate his insights.

Next I teach another pair of similarly-themed novellas by Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata and The Devil. These both deal with the hypocrisy of polite society with regard to marriage. Like Schopenhauer, Tolstoy believed that what we call love is little more than lust by another name, a biological drive that we romanticize, and that marriage is usually misery, and inevitably leads to deceit and infidelity. Once again, he is utterly unsentimental. Aside from his frankness, which one does not find in British or American writing of the period, another of his virtues is the clarity of his thought—and of his prose. Like all great writers, he understands that profound ideas do not need to be cloaked in abstruse prose. Indeed, “difficult prose” is the refuge of the writer who is not deep, but confused. (Sorry, Derrida.) Why else do we read Tolstoy? For his great psychological insight, and of course because he can rattle off a story that is impossible to put down.

Next I teach another pair of similarly-themed novellas by Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata and The Devil. These both deal with the hypocrisy of polite society with regard to marriage. Like Schopenhauer, Tolstoy believed that what we call love is little more than lust by another name, a biological drive that we romanticize, and that marriage is usually misery, and inevitably leads to deceit and infidelity. Once again, he is utterly unsentimental. Aside from his frankness, which one does not find in British or American writing of the period, another of his virtues is the clarity of his thought—and of his prose. Like all great writers, he understands that profound ideas do not need to be cloaked in abstruse prose. Indeed, “difficult prose” is the refuge of the writer who is not deep, but confused. (Sorry, Derrida.) Why else do we read Tolstoy? For his great psychological insight, and of course because he can rattle off a story that is impossible to put down.

The last of his novellas that we study in the first three weeks of my course is Hadji Murat, which Harold Bloom described as “the best story in the world.” If that sounds overblown to you, and if the subject matter doesn’t appeal—it’s the story of a mid-nineteenth century Muslim fighter (what would now be called a ‘terrorist’) who betrays the Chechens and goes over to the Russians—just try it. In a hundred pages he packs in adventure, treachery, cruelty, courage, honour, political machinations, gambling addiction, love, and much else. Most of all, without sentimentalizing his Muslims at all, he makes them sympathetic figures, far more sympathetic than the “civilized” Russians. And how many contemporary western writers have managed that? (I have tried.)

Of course there are brilliant novellas in English too. Several of Joseph Conrad’s could stand in the august company of Tolstoy et al, especially Heart of Darkness, one of my favourite works of fiction. Some of D.H. Lawrence’s might too. And Phillip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus could perhaps find a place on the same shelf. Muriel Spark is awfully good as well. Still, I can’t think of a better place to start, if you want to write great fiction, than Tolstoy. And if the doorstop novels frighten you off, start with the novellas. They’re far better than most of the full-length novels you’ve read.

Of course there are brilliant novellas in English too. Several of Joseph Conrad’s could stand in the august company of Tolstoy et al, especially Heart of Darkness, one of my favourite works of fiction. Some of D.H. Lawrence’s might too. And Phillip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus could perhaps find a place on the same shelf. Muriel Spark is awfully good as well. Still, I can’t think of a better place to start, if you want to write great fiction, than Tolstoy. And if the doorstop novels frighten you off, start with the novellas. They’re far better than most of the full-length novels you’ve read.

Reference

Tolstoy, Leo, and Pevear, R. and Volokhonsky, L. (trans). Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories. Vintage, 2010. Print.

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)