Writing in the Echo Chamber

Much hand-wringing and self-examination has taken place since the US Presidential election about why so many people, political pundits and journalists included, were blindsided by the result. The ‘echo chamber’ as a metaphor for social media has been the most frequently cited cause. Nowadays most of us, the argument goes, get our news from Twitter or Facebook feeds. This is true, not only for the millennials, but equally or almost so for older generations. Because most of us are reading ‘news’ (more often opinion, when it comes down to it) from our friends, who are likely to share our views, there’s a danger that our prejudices are never challenged and that we live increasingly in a world that bears little resemblance to reality. As an academic, I can confirm that this is the case for most professors, who are hardly better informed on matters of global economics and politics than the elusive and mythical ‘man in the street’. (Or woman.)

But if this is true of our political life, isn’t it true of our cultural life, too? Have we thought deeply enough about the consequences of reading literature that’s written by people like us, too? I don’t think so. A few years ago the British novelist Jeannette Winterson (if you haven’t heard of her, this proves my point) who was herself teaching in a graduate creative writing program at Manchester University, criticized American programs for teaching exclusively contemporary Americans. This, she argued, was the reason for the dullness and uniformity of current American letters, a point that echoes similar arguments by Anis Shivani and others.

This is not to suggest, obviously, that contemporary Americans shouldn’t be taught at all. Naturally there are excellent ones, and of course students need to be familiar with the professionals they are competing with, or soon hope to be competing with. However, I find that most of my students, at least at the graduate level, do have an acquaintance with the more famous writers—in fiction, for example, names like Franzen, Eggers, Russell and July are well-known to them (in spite of their mediocrity). So do they really need to study them in class? In particular, do they really need to study the usually mind-numbingly awful anthologies like Best American Poetry and Best American Short Stories which are so often the staple fare of workshop courses?

It’s a rare American graduate student that has read even the great British novelists of the second half of the twentieth century, people like Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, Iris Murdoch or Penelope Fitzgerald. (And very often they haven’t even heard of them!) And these are important writers, by any standard, in their own language. When you come to the giants of the past century from other cultures—incredibly, I’m talking about writers like Kafka, Borges, Thomas Mann, García Márquez, Isak Dinesen—they may have heard of them, but usually haven’t read them. So what happens in most creative writing courses, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, is this: professors teach contemporary Americans because (a) they are familiar with them, (b) they know their students will not be too challenged by them, and (c) they feel they are ‘relevant’. Perhaps I should add (d): they often claim that their choices of reading material are motivated by a desire for diversity, and point to the ethnicity or sexual orientation of the writers they choose to justify this, forgetting that, usually, every single one of these writers is American and all have gone through the same MFA mill, so there’s almost no aesthetic diversity. And—let’s be honest—most of the writers they teach are not great. They are competent, (if nothing else, the proliferation of writing programs has taught craft competently) and occasionally inspired, but in general familiar mediocrity is taught in lieu of brilliance, which could easily be within the students’ purview if only the curriculum were genuinely diverse.

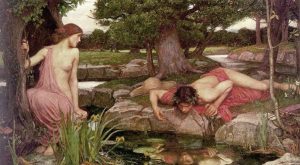

It’s bizarre if you think about it. No school of music would retain any credibility if it taught only American composers; any art school that taught just American painters and sculptors would be a laughing-stock. And yet at most writing programs, most professors—sometimes all—teach exclusively or nearly exclusively contemporary American writers. The result, obviously, is a kind of national solipsism: the all-too familiar phenomenon of American writers gazing at their own navels and writing about them at Joycean length because they are convinced that anything they write about themselves must be fascinating, because after all, they are all very special people.

So for some years now I have done pretty much the obverse: taught exclusively, or practically exclusively, writers from other cultures. (I occasionally teach an American story for comparison: and good ones too: I’m not trying to turn my students off American literature.) And what is the result? Sometimes there are protests, particularly at first. ‘These Brits all use unnecessarily long words and flowery language’; ‘The Latin Americans are boring: all they ever do is talk about philosophy and politics’; ‘That Japanese dude weirds me out.’ But I find that many students who are exposed to different ways of writing start experimenting more in their own work. They become more ambitious (as very little current American fiction is, except, sometimes, formally.) They take on deeper themes; they cast off their fears of exposition and summary; they enter into dialogues with authors from other continents and centuries; they challenge their own intellectual assumptions, and their readers’. Surely if we wish to have a vibrant literature, this is essential?

Like most people who have dared to criticize writing programs, I have been misunderstood and sometimes maligned. So let me be clear: For me, this is not a zero-sum game. The fact that writing programs are usually parochial, and that many professors are timid and middle-of-the-road in their tastes, and intellectually unengaged, does not mean that the whole enterprise should be abolished, ineluctably. It was necessary to create writing programs because so many literature programs were too elitist and canonical, and students could not relate to what they were being taught. The best way to teach literature, in my view, as well as writing, is by learning to read as a writer does, and trying out the making of stories, poems or plays or essays for yourself. But heaven knows, we could be doing a far better job. It really isn’t rocket science!

The best start would be to begin to introduce writing students to the literature of other cultures: the fiction of Japan and Latin America, the poetry of Portugal and Persia, the plays of Norway and Russia. At the very least teach them current British and Commonwealth literature, which is so much more vibrant and exciting than most of what’s being produced in this country now.

Writing risks becoming a ‘racket’, as it’s increasingly corporatized—the yearly corporate shindig, the AWP Conference, is just around the corner in benighted Washington, D.C.—and more and more the criteria of big business determine what publishers accept and promote. Will it sell? How much? How hip is this author? How can she be promoted? What does she look like? What’s the angle? We must resist this. First and foremost, we are artists, not entrepreneurs. Therefore let us immerse ourselves in the greatest art, and endeavour to match it or surpass it, without concerning ourselves about the damned market. Leave that to the money-grubbers and nonentities who are dazzled by celebrity.

Echo and Narcissus by John William Waterhouse (1903), The Walker Gallery

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)