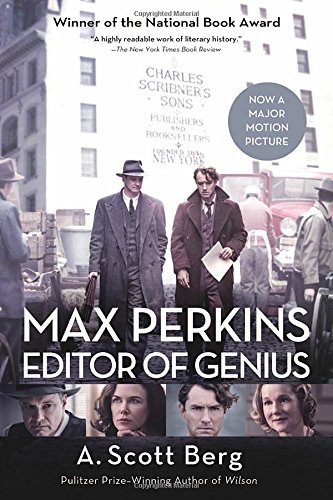

MAX PERKINS—THE EDITOR EVERY WRITER YEARNS FOR

Most fiction fans know about Maxwell Perkins’s role in paring down  Thomas Wolfe’s sprawling narratives to shape them into manageable novels. Fewer people are familiar with the massive influence Perkins had on other iconic American fiction writers and on the literary standards of the early 20th century. Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, the National Book Award winner by A. Scott Berg, tells Max’s story with all the color and style worthy of its subject. Filled with details and personalities, the biography reads like a novel, following the brave exploits of its central character.

Thomas Wolfe’s sprawling narratives to shape them into manageable novels. Fewer people are familiar with the massive influence Perkins had on other iconic American fiction writers and on the literary standards of the early 20th century. Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, the National Book Award winner by A. Scott Berg, tells Max’s story with all the color and style worthy of its subject. Filled with details and personalities, the biography reads like a novel, following the brave exploits of its central character.

Max Perkins joined Charles Scribner’s Sons as advertising manager in 1910. When he moved to the editorial department four and a half years later, Scribner’s was one of the most conservative publishing houses in New York. Its books never went beyond the bounds of “decency,” and it had none of the newer writers such as Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis. When a manuscript by a young army officer crossed the editors’ desks, Perkins was the only one who liked it. Although the senior editors forced Perkins to reject the novel, he wrote the author an encouraging note, which was against the Scribner’s policy of not commenting on rejections.

The author revised the novel and sent it back two more times. On his third effort to sway the senior editors, Perkins said, “A publisher’s first allegiance is to talent. And if we aren’t going to publish a talent like this, it is a very serious thing. . . . I will lose all interest in publishing books.” Charles Scribner, patriarch of the firm, reconsidered and accepted This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The novel sold well, but Scribner’s was slow in paying royalties, and Fitzgerald began asking Perkins for more advances against receipts. Thus began a pattern of money lending that would endure throughout their relationship. Realizing that Fitzgerald could not manage money, Perkins did not offer a large advance for the next novel, but rather agreed to consider Fitzgerald’s requests for money one at a time.

Becoming Fitzgerald’s financial overseer was typical of the relationships Perkins cultivated with his authors. Whatever role they needed him to play, he provided—editor, counselor, father, friend. And sometimes gossiper. Perkins was not averse to talking to his writers about other writers he worked with or wanted to work with. In the case of Ernest Hemingway, the gossip paid off.Perkins tried several times to land Hemingway as a client, but each time Hemingway went with another publisher. In the meantime Fitzgerald and Hemingway had become friends in Paris, and Perkins told Fitzgerald how sorry he was not to be working with Hemingway. Fitzgerald sang Perkins’s praises to Hemingway, and when Hemingway needed a publisher for a satire called The Torrents of Spring and a new novel called The Sun Also Rises, he turned to Perkins. Their relationship was more like brothers with the role of older brother shifting depending on whether they were working on novels or fishing.

Thomas Wolfe became the son Perkins never had. The father of five daughters, Perkins always wanted a son, and he saw in Wolfe the writing genius he would have wanted to nurture in a son. Although astonished by the size of the novel (between 250,000 and 380,000 words) brought to him by a literary agent for Wolfe, Perkins eventually plowed through it and marveled at some of the scenes tucked away in the pages.

His first suggestion to Wolfe was that he cut the first 100 pages because they dealt with the father of the main character, Eugene, and Perkins thought the only way to give shape to the narrative was to frame it within Eugene’s experience and memory. Wolfe wasn’t agreeable to such radical cuts then, but he wasn’t put off, either. Eventually, he agreed to work with Perkins, and Scribner’s took on the novel, which was then called O Lost.

The two men set up a working pattern, which usually involved Perkins suggesting a cut, discussing and arguing about it with Wolfe, and then Wolfe making the deletion. Perkins’s criterion throughout the painful process was that the interaction between Eugene and his family was the focus of the book and anything that led the reader away from this focus had to be cut. After months of give and take, O Lost became Look Homeward, Angel.

When Wolfe’s agent saw what Perkins had done with the novel, she asked him why he didn’t write. She was sure he could do better than most people who write. Perkins stared at her for a long time and then said, “Because I’m an editor.”

Perkins cared about his authors’ work as much as they did. When Fitzgerald gave him The Great Gatsby, then called Trimalchio at West Egg, Perkins knew it was an extraordinary novel, but he also knew the character of Gatsby was too vague. Among many suggestions, he urged Fitzgerald to give a more detailed description of Gatsby and to give him some recurring characteristics like the use of the phrase “old sport.”

Scott Berg has taken a familiar but vague outline of a respected editor and fleshed out the character until he is a living, breathing human being with remarkable talent and compassion. The depth of research for Max Perkins: Editor of Genius is obvious. In his acknowledgements, Berg says he relied almost entirely on primary source material, including interviews with family, colleagues, and friends, and 100 handwritten letters Perkins sent to his friend Elizabeth Lemmon. The biography includes 29 pages of sources and notes.

In 2016, Max Perkins: Editor of Genius was adapted for the movie Genius staring Colin Firth. The movie is excellent, but it only scratches the surface of its main character. To appreciate the complexity of Maxwell Perkins, read the book.

Sally Whitney

Sally Whitney is the author of When Enemies Offend Thee and Surface and Shadow, available now from Pen-L Publishing, Amazon.com, and Barnesandnoble.com. When Enemies Offend Thee follows a sexual-assault victim who vows to get even on her own when her lack of evidence prevents police from charging the man who attacked her. Surface and Shadow is the story of a woman who risks her marriage and her husband’s career to find out what really happened in a wealthy man’s suspicious death.

Sally’s short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017, Main Street Rag, Kansas City Voices, Uncertain Promise, Voices from the Porch, New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers and Grow Old Along With Me—The Best Is Yet to Be, among others. The audio version of Grow Old Along With Me was a Grammy Award finalist in the Spoken Word or Nonmusical Album category. Sally’s stories have also been recognized as a finalist in The Ledge Fiction Competition and semi-finalists in the Syndicated Fiction Project and the Salem College National Literary Awards competition.

- Web |

- More Posts(67)