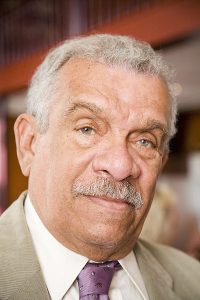

Remembering Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott, 1930-2017

I used to read a lot of poetry. That thought hit me on March 17, when I learned of the death of the Nobel Prize-winning poet and playwright Derek Walcott on the island of St. Lucia, where he was born.

I used to read a lot of poetry. That thought hit me on March 17, when I learned of the death of the Nobel Prize-winning poet and playwright Derek Walcott on the island of St. Lucia, where he was born.

It has been years since I’ve read Walcott, but his work was once a constant companion of mine. As I think now about the pleasures of meter, rhyme, and the soaring imagination that good poetry generates, I realize what I’ve missed.

When I heard of Derek Walcott’s death, I recalled a day in 1980 when I opened The New Yorker and excitedly read the title “Jean Rhys” above a six-stanza poem. Only a short time before had I become acquainted with the Dominica-born author Jean Rhys, but I’d been devouring her novels Wide Sargasso Sea, Good Morning, Midnight, and Voyage in the Dark and recommending them to every book lover I knew. And here was an homage to her in a poem by Walcott. I calmed myself and read:

“In their faint photographs

mottled with chemicals,

like the left hand of some spinster aunt,

they have drifted to the edge of verandas in Whistlerian

white …”

“The left hand,” “the WhistIerian white” —Each phrase said so much about time and place and sorrow. And I read on, coming to the last stanza:

“There are logs

wrinkled like the hand of an old woman

who wrote with a fine courtesy to that world

when grace was common as malaria …”

“Grace was common as malaria”– Who is this man who could conjure such an image, I wondered.

Derek Walcott’s heritage was English, Dutch, and African, his education was largely Eurocentric, and he was a Methodist in a place largely Catholic. Both parents were racially mixed. His father, a watercolorist, died when he and his twin brother were babies, and his mother, a schoolteacher, helped him publish his first collection of poems. Walcott published his first poem in a local newspaper when he was only fourteen.

His poetry is rich with metaphors, so descriptive and detailed that they convey pictures of place and people. This attention to imagery shouldn’t be surprising in a writer who was the son of a painter and was himself a painter.

Walcott’s poetry is rooted in the place of his birth, his search for identity, and his outlook, which stretches back to ancient times. These are the tensions, the beauty, and the sweep in his writing.

Walcott achieved international fame and recognition: the MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, a Royal Society of Literature Award, the Queen’s Medal for Poetry, honorary membership in the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters as well as the Nobel Prize awarded in 1992.

His most celebrated poem is Omeros, a 325-page retelling of the Odyssey, but even in smaller works, like the 117-page collection Arkansas Testament, one of my favorites, you can see his versatility and range. Arkansas is in two parts, “There,” evoking the Caribbean, and “Elsewhere.” The poem that lends its name to the title showcases his attention to detail and to scope, as in these lines:

“I fell back on the double bed

like Saul under neighing horses

on the highway to Damascus,

and lay still, as Saul does,

till my name re-entered me,

and felt, through the chained door,

dark entering Arkansas.”

In his speech at the Nobel Prize ceremony, Walcott explained the methodical way in which poets choose their words: “The original language dissolves from the exhaustion of distance like fog trying to cross an ocean, but this process of renaming, of finding new metaphors, is the same process that the poet faces every morning of his working day, making his own tools like Crusoe, assembling nouns from necessity, from Felicity, even renaming himself.”

We can thank Felicity, a town in Trinidad, and other towns and books and everything that inspired Walcott.

Janet Willen

Janet Willen is author of Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery (2015) and Five Thousand Years of Slavery (2011), written with Marjorie Gann and published by Tundra Books. Publishers Weekly called Speak a Word for Freedom an “engrossing study of female abolitionists from the 18th century to the present day” and gave the book a starred review. Five Thousand Years of Slavery was named a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association and a Silver Winner in young adult nonfiction of ForeWord Reviews, and it received a starred review from School Library Journal. A writer and editor for more than thirty years, Janet has written many magazine articles and has edited books for elementary school children as well as academic texts and a remedial writing curriculum for postsecondary students. Janet lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.