A Conversation with Saikat Majumdar

I spoke with Saikat Majumdar last April about his recent novel, The Firebird, in an interview for the Los Angeles Review of Books and Scroll.in. With the 2017 release of the American version of the novel, I had the pleasure of catching up with the novelist and critic again for LLNB.

Joseph Daniel Haske: What have you been up to lately? It seems like you’ve been traveling quite a bit recently. What effect does this have on your writing, if any?

Saikat Majumdar: Yes, there has been quite a bit of travel and scene-shifting in my life lately. Currently I’m in Delhi where I direct the new Creative Writing Program of a liberal arts university here, Ashoka, and teach literature, critical theory, and fiction workshops.

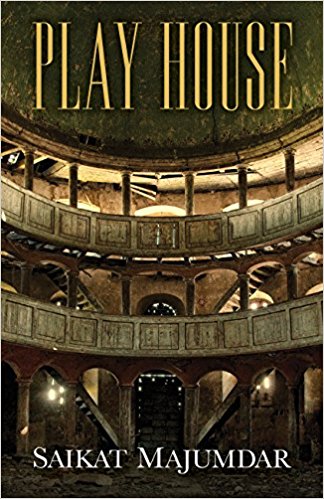

Most of 2017-18 will be spent in the Boston area, where I’ll be a Fellow at the Newhouse Center for the Humanities at Wellesley, and traveling a bit in the US for talks and readings around the new US edition of my novel The Firebird, re-published here as Play House. Part of summer will be spent in Calcutta, working with the Los-Angeles-based filmmaker, Bedabrata Pain, on developing the screenplay for The Firebird/Play House as it gets adapted as a feature film. We plan to walk through the streets of Calcutta where the novel is set while he writes the screenplay.

I’ve long since realized that I need to travel “away” from a place to write about it. Much of my fiction has been set in Calcutta and Bengal, already separated by time from the “now”, and then by place too. I’ve written about these places from northern California; now from Delhi, and in the autumn will do so from Boston. Just as you take the writer out of the place, you insert the place even more deeply in him.

JDH: Are you able to keep a regular writing routine? Could you describe your creative process for fiction? How are you able to balance family life, academics, and fiction writing?

SM: Yes, more or less; I’m something of a compulsive writer, though it is a very exhausting compulsion. Writing is interspersed by long periods of editing (often pretty crappy first drafts), and reading, especially with the new nonfiction book. With fiction, it always begins when I’m compelled by some experience, sometimes a lingering memory that lingers so richly that it feels like an immediate experience. Something which is magnetic but of which I cannot make full sense; it’s almost like a raw physical sensation. This sensation shapes the voice and the narrator, and then slowly it is fleshed out; sometimes a story raises its head, other characters come to life. And then as I write, the experience starts to make some sense, though it is nothing like an authentic or ‘correct’ interpretation (if such things even exist). Often, it seems to me in hindsight, it’s a pretty wrongheaded take on things, but one with a wild force of its own. It’s the force that counts, not the ‘correctness.’

One good thing about the writerly life is that you can do most of it from home, and so, flanked by the children. Not that you are a very attentive parent when you’re doing that, but at least you are physically there, and you can always take short breaks to play with them, or read them a story. The thing you don’t realize is that when they see so much of you doing a particular thing (sitting and scribbling on my laptop in this case), they want to do the same thing. So my daughter, who is now seven, started typing her letters on the laptop pretty early, and now my son, who is three, clamors to do the same whenever I’m writing, though thankfully he’s not as quick a learner as she was.

JDH: Have your children taken an interest in your writing? Have they formed any opinions about having a novelist for a father and academic parents?

SM: Pretty literally, as you can see above. But also beyond that with my daughter. I’ve been telling her stories for a long time, especially as I put her to bed. Most of them are scary stories, and according to most people, completely inappropriate for children. My daughter is scared stiff by the stories and yet always asks for more. And then she’s pieced together the plot of my being a novelist from my books, interviews etc. she sees (she’s going to read this one with great interest), and from readings and talks she’s attended. The net result is that she doesn’t believe anything I say. She thinks I make up everything (kind of true, that, with her), and has to run everything by her mother who is the real and the practical one. Books and stories are now to her like a dangerous but irresistible kind of addiction. She writes long stories about adventures – usually involving princesses and little orphaned girls (often the same people) – but since her mother has expressly forbidden her becoming a writer, she declares emphatically that she’s not a writer but just one who writes. The son, at three he’s confined to demanding the laptop (and my phone) from time to time to “lite” (write), and I’ve carved out several sentences in between kicking around a ball with him (I fling the ball faraway in the house and I get at least thirty seconds to complete the sentence before he comes back with the ball, like a puppy).

JDH: Since you’re quite familiar with both American and Indian literary culture, what are some differences and similarities that you’ve noticed? With The Firebird, specifically, how has the American readership responded as opposed to the Indian readership?

SM: There is a (still) strong non-mainstream literary culture in the US, made up of influential small presses and literary magazines. There isn’t much of it in India these days, except a bit with poetry publishing, though I believe there was quite a bit of it in the decades following independence. Or perhaps the past always looks richer in hindsight – I’m not quite sure. Anyway, now it seems either mainstream/commercial or bust, and there aren’t any influential literary magazines either. Another difference: US literary culture can be insular at times; only a small niche is interested in writing from overseas, though there is great publishing and university infrastructure to support international writing here. People who read English-language books in India have almost by default looked outside the country, though now that’s changing with the explosion of English-language writing and publishing within the country. Probably the biggest difference is marked by the MFA culture, which to a degree defines US literary culture but does not exist in India.

The US edition of The Firebird, called Play House here, just came out at the end of April and it’s still early to read its reception, except for the pre-reviews in places like Publishers’ Weekly and early discussions on a few blogs and Goodreads. But the novel actually debuted in 2015 through early excerpts in two American magazines, The Kenyon Review and World Literature Today, which created some interest in the book here. Then there were some special readers like you who read the 2015 South-Asian edition, following which we had that great conversation in the Los Angeles Review of Books; the drama-theorist Keri Walsh who interviewed me for Public Books. A bit surprisingly perhaps, the (small) American readership has responded to the book more or less like the Indian readership, as a human narrative above all else, which is interesting for a book so locally rooted. The editor who took it here knows very little about India, and yet I was so moved by his response to the novel. But the response of readers at large, well, it is too early to assess that.

JDH: Tell us more about the American version of The Firebird (Play House)? Were there any significant modifications to the manuscript with this edition?

SM: As I said, Play House was just launched – on April 30 this year from The Permanent Press in New York. No major modifications except the title which they wanted to change, a little against my wish. It was proofread once more and we caught a few errors, and all non-English words have been italicized on the first occurrence. A new cover of course. Other than that it’s the same book.

JDH: What are you working on now?

SM: I’m working on a new novel about a young boy’s fascination with Hindu monastic life; I’m about a little more than halfway into the manuscript. Also editing the manuscript of a nonfiction book on postsecondary education in India, which is due out around the end of this year. I did not realize this before, but the new novel is turning out to be something of a psychological sequel to The Firebird/Play House, though with a very different theme – Hinduism and alternative sexuality – and with different people. But behind the screen, I guess the characters in Play House haven’t quite exhausted themselves yet.

JDH: Glad to hear it. Keep up the excellent work. I look forward to talking again soon!

Majumdar’s Play House is currently available from The Permanent Press and other major booksellers:

http://thepermanentpress.com/index.php/play-house.html

Joseph D Haske

Joseph D. Haske is a writer, critic and scholar, whose debut novel, North Dixie Highway, was released in October 2013. His fiction appears in journals such as Boulevard, Fiction International, the Texas Review, the Four-Way Review, Pleiades, and in the Chicago Tribune‘s literary supplement, Printers Row. His poetry and fiction are also featured in various anthologies as well as in French, Romanian and Canadian publications. Haske edits various literary venues, including Sleipnir and American Book Review. He is professor of English at South Texas College.