Reading Elizabeth Strout as a Writer Would

A Writer Reads Elizabeth Strout

Writing fiction will change the way you read it. I often make a point of reading like a writer (to borrow Francine Prose’s book title), examining what the author is trying to do and how she’s doing it, determining what works and what doesn’t (and why), and looking for how this can help improve my own writing. It doesn’t stop me from reading as a reader—enjoying good literature and losing myself in fictional worlds—but I rarely lose sight of what the author is doing to and for me.

Writing fiction will change the way you read it. I often make a point of reading like a writer (to borrow Francine Prose’s book title), examining what the author is trying to do and how she’s doing it, determining what works and what doesn’t (and why), and looking for how this can help improve my own writing. It doesn’t stop me from reading as a reader—enjoying good literature and losing myself in fictional worlds—but I rarely lose sight of what the author is doing to and for me.

And when I read really good fiction—the kind that strikes a chord deep within—the writer in me usually has two reactions. First, I’m inspired and I want to rush to the computer to try to create a similar gift for my readers. But often the inspiration gets deflated by a feeling that I’m not a real writer, not the kind of author who wields magic—who not only understands people and the world they live in, but also has the tools to effectively convey that.

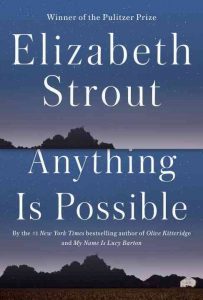

Such was my reaction to Elizabeth Strout’s new collection of stories, Anything Is Possible.

The book is sort of a sequel to My Name is Lucy Barton, which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2016. I say, “sort of a sequel” because it’s also part prequel. Its present-day events follow those in the first book, but most of the stories flesh out the early life of Lucy and the characters mentioned in the novel.

The nine linked stories in Anything Is Possible are remarkable on several levels. Strout is a master of both structure and style. Her work is meticulously planned so events and feelings curl around and back to develop seeds planted earlier. And her writing style is both awesome and modest. Elizabeth Day, reviewing Strout’s work in The Guardian, says Strout’s writing “has no ego and the sentences she creates are to serve characters, rather than the author.” That’s exactly right.

Strout’s new collection will undoubtedly remind readers of her hugely successful earlier book, Olive Kitteridge. The similarities in form are obvious, but so too is the focus on providing quiet portraits of ordinary people suffering the disappointments and indignities of everyday life. There is also a similar focus on class. All of the stories in the new book ultimately deal with a question posed by Lucy Barton in the novel, “What is it about someone that makes us despise that person, that makes us feel superior?” Strout’s characters are usually on the receiving end of that question; they’re the despised, not the ones who feel superior, but that’s probably the better angle from which to attack the question.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in “Dottie’s Bed and Breakfast,” the story that most affected me, undoubtedly because a B&B plays a prominent role as the setting of my own novels. Strout does so much more with the setting that it almost made me weep at my own deficiencies, though it also made me realize how much more I can and will try to do in the next one I write.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in “Dottie’s Bed and Breakfast,” the story that most affected me, undoubtedly because a B&B plays a prominent role as the setting of my own novels. Strout does so much more with the setting that it almost made me weep at my own deficiencies, though it also made me realize how much more I can and will try to do in the next one I write.

The action in the story begins with the arrival of new guests:

“…the reservation was made for Mr. and Mrs. Small, and two weeks later a tall—big—white-haired man stepped through the door and said, ‘We have a reservation for Dr. Richard Small.’ Dr. Small’s announcement was apparently large enough to include his wife, who came in right behind him, without any mention of her at all.

“Standing at the front desk, he did the registering with terrible penmanship, irritation oozing out of him, while Mrs. Small—who was very thin and had a look of general nervousness about her—glanced politely around the lounge, and then became interested in the old photographs of the theater that were on the wall, and she seemed to especially like a photograph of the library back in 1940 looking brick-and-ivy old-fashioned, so Dottie had a sense about this woman—and her husband!—right away. Of course, in Dottie’s business she would have a sense about people right away. Sometimes of course Dottie was wrong.”

With the Smalls, Dottie proves right about the husband, less so about the wife, who corners Dottie one afternoon in the lounge and confesses all sorts of personal secrets, only to get angry at Dottie, presumably for having listened. The secrets, which involve disappointments with her marriage and how others view her, don’t surprise or shock Dottie, who “saw Shelly Small as a woman who suffered from the most common complaint of all: Life had simply not been what she thought it would be.”

It is this general disappointment with the hand life has dealt—coupled with a desire to make the most of it anyway—that runs through Strout’s stories and leaves the reader with a better understanding of the struggles we all face. There are few people who better understand these “normal” people than Strout, and even fewer authors who have the ability to tell their stories the way they need to be told. Don’t miss Anything Is Possible.

Mark Willen

Mark Willen’s novels, Hawke’s Point, Hawke’s Return, and Hawke’s Discovery, were released by Pen-L Publishing. His short stories have appeared in Corner Club Press, The Rusty Nail. and The Boiler Review. Mark is currently working on his second novel, a thriller set in a fictional town in central Maryland. Mark also writes a blog on practical, everyday ethics, Talking Ethics.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(48)