A Book to Capture Your Imagination

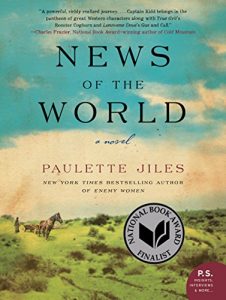

The 2016 novel News of the World by Paulette Jiles is beautiful, poetic, and riveting, and takes you to a world that’s familiar but full of mystery, all in just 240 pages. It fascinated me so much that I immediately sought out information on the history behind the fiction — the lives of children captured by Native Americans in mid-nineteenth-century Texas.

The 2016 novel News of the World by Paulette Jiles is beautiful, poetic, and riveting, and takes you to a world that’s familiar but full of mystery, all in just 240 pages. It fascinated me so much that I immediately sought out information on the history behind the fiction — the lives of children captured by Native Americans in mid-nineteenth-century Texas.

News of the World tells the story of Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, a seventy-one-year-old widower and Army veteran who travels the towns of North Texas entertaining audiences by reading selected articles from national and international newspapers. After one reading, an acquaintance, Britton Johnson, asks him to return a ten-year-old white girl to an aunt and uncle, her nearest living relatives, who live hundreds of miles away, near San Antonio. The child had recently been freed after spending four years with the Kiowa Indians, who’d captured her during a raid in which they’d killed her parents.

To the Kiowas, the girl was known as Cicada, but Captain Kidd calls her Johanna, the name her white German-speaking parents had given her, though “She doesn’t know the name Johanna from Deuteronomy,” he tells himself.

The task facing Captain Kidd is overwhelming. Johanna is a feral child. “I am astonished,” Kidd says. “The child seems artificial as well as malign.” But Kidd believes it is adults’ duty to protect children, and he is the only one at hand to help her.

The child’s fears, sorrow, and anger are sensitively drawn. Jiles researched the lives of children captured by Indians and uses the words of her characters to explain the young captives’ struggling emotions. Britt Johnson, for example, understands the plight of captured children because his son had been in captivity. “…[He] came back different,” Johnson says. “Roofs bother him. Indoor places bother him.” (Jiles patterned Johnson after a historical figure also named Britt Johnson, a former slave who had rescued his wife and two daughters from Indians.)

Doris, another character, says, “You can put her in any clothing and she remains as strange as she was before because she has been through two creations.” Birth is the first creation, and the second tears the first to bits.

Doris, another character, says, “You can put her in any clothing and she remains as strange as she was before because she has been through two creations.” Birth is the first creation, and the second tears the first to bits.

Kidd describes Johanna’s torment in a few heart-wrenching paragraphs after she tries to escape and return to the Kiowa people. He comes upon her during a torrential downpour as she stands at one side of a river, appearing to beseech Indians on the other side to rescue her. “What could she think would happen,” Kidd asks himself. “She was shouting for her mother, for her father and her sisters and brothers, for the life on the Plains, traveling wherever the buffalo took them, she was calling for her people who followed water, lived with every contingency, were brave in the face of enemies.” If the Indians notice her at all, they see a white child with blond hair. They ignore her.

And so Johanna stays with him.

As Kidd and Johanna travel together, they begin to understand each other. It seems at first that they have no common language, but then she makes the sign for fire. He knows a little of the Plains Indians signs, so he can respond. He can say a few words in German, and she shows recognition of that language. She tries out English words. They grow to trust and respect each other. She realizes that he is taking care of her, and he recognizes her intelligence.

Kidd holds readings as they arrive in new towns. He carefully chooses his topics so that they entertain as much as they inform, while avoiding contentious topics that could disrupt the crowd. He tells the audience about the Fifteenth Amendment, which extends the right to vote to all men regardless of race, warning, “That means colored gentlemen. … Let us have no vaporings or girlish shrieks.” Then he astounds them with stories from as far away as Chile and from a polar exploration ship, “trying to bring them distant magic that was not only marvelous but true.” How Kidd selects his stories and the audiences’ reactions are fascinating and, to me, in our own days of instant news, make the 1870s seem very long ago.

Just as Kidd transported his audience, Jiles transported me.

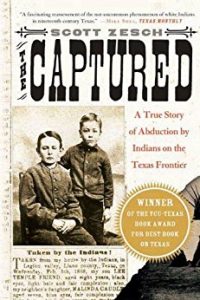

She surely knew that some of her readers would want to know more about children captured by Native Americans, and indeed I did. In a note, she recommends The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier by Scott Zesch. I immediately checked my library for the book and saw that I had to put it on hold. (Perhaps all Jiles’ readers go from her book to his.) It was worth waiting for.

She surely knew that some of her readers would want to know more about children captured by Native Americans, and indeed I did. In a note, she recommends The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier by Scott Zesch. I immediately checked my library for the book and saw that I had to put it on hold. (Perhaps all Jiles’ readers go from her book to his.) It was worth waiting for.

Zesch profiles six children who had been captured and subsequently “rescued.” Like the fictional Johanna, many of them seemed to live between two worlds. It’s a fascinating story of a not-so-distant and troubling time.

My advice: Start with News of the World and continue with The Captured. They work beautifully together.

Janet Willen

Janet Willen is author of Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery (2015) and Five Thousand Years of Slavery (2011), written with Marjorie Gann and published by Tundra Books. Publishers Weekly called Speak a Word for Freedom an “engrossing study of female abolitionists from the 18th century to the present day” and gave the book a starred review. Five Thousand Years of Slavery was named a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association and a Silver Winner in young adult nonfiction of ForeWord Reviews, and it received a starred review from School Library Journal. A writer and editor for more than thirty years, Janet has written many magazine articles and has edited books for elementary school children as well as academic texts and a remedial writing curriculum for postsecondary students. Janet lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.