Literary Fall: An Interview with Liana Vrajitoru

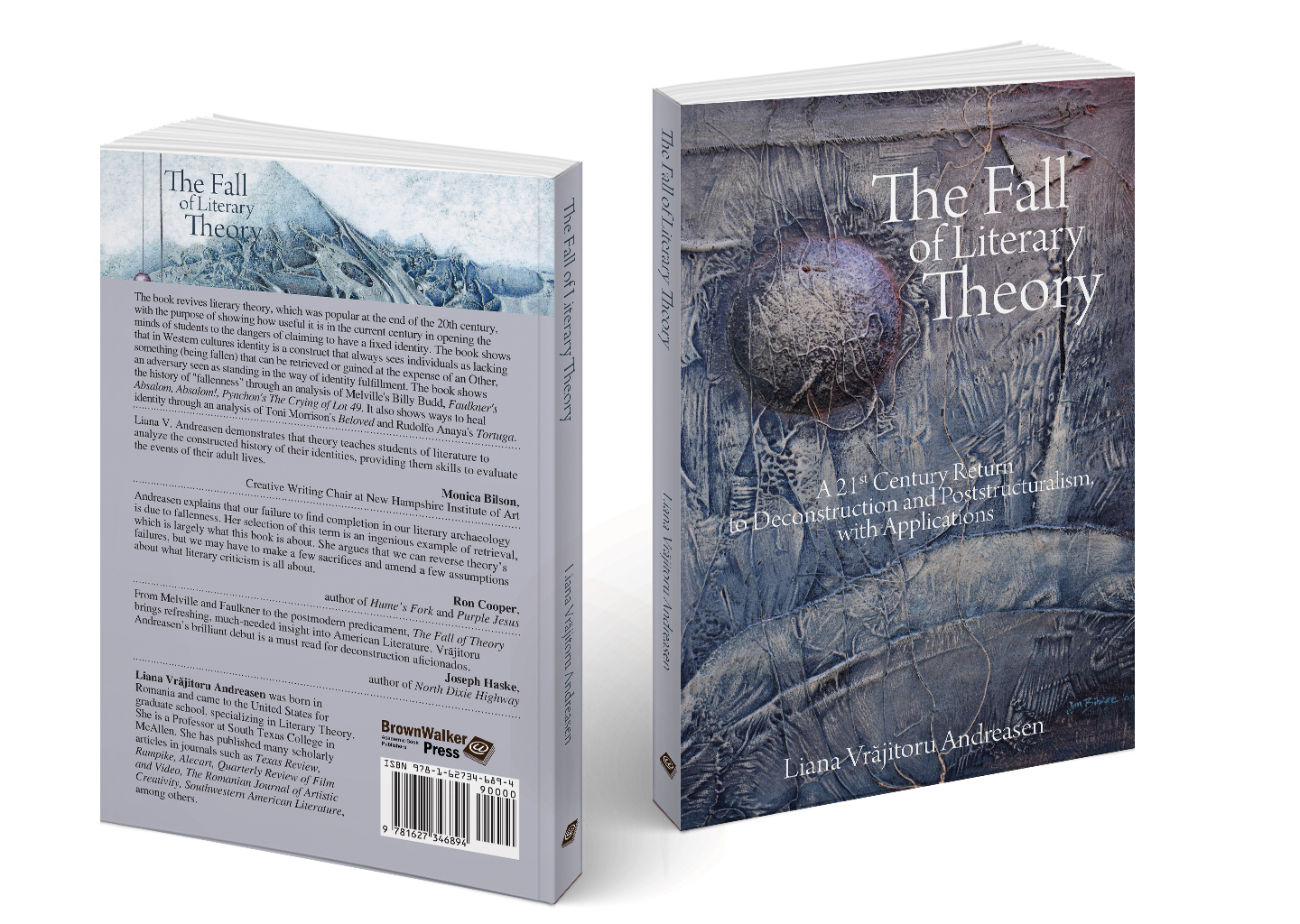

Liana Vrajitoru Andreasen is a scholar, professor, and writer from Romania who has been living and working in the United States for over twenty years. Her work has appeared in journals such as: Rampike, Alecart, Texas Review, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, The Romanian Journal for Artistic Creativity, Southwestern American Literature, The CEA Critic, American Book Review, Lumina, Fiction International, Calliope, The Raven Chronicles, The Willow Review, Mobius, a Journal of Social Change, Scintilla, and Weave Magazine. I recently enjoyed the opportunity to speak with her about her forthcoming critical book, The Fall of Literary Theory.

Joseph Daniel Haske: Tell us about your new book, The Fall of Literary Theory. How long have you been working on it and what was the motivation/philosophy behind it?

Liana Vrajitoru Andreasen: This book has a bit of history to it, so to speak, in the sense that I worked on it in layers and stages. Most recently, two-three years ago, I started to wonder why literary theory seemed to have been tossed to the side and to have become an embarrassment in some academic circles. I certainly was still in love with it (I still am), fascinated by the many ways in which it has provided a playground for the questioning mind, a fertile ground for the meeting of philosophy, literature, linguistics, psychoanalysis, social activism, and so on. I could see in very practical terms how, in my classes, the direct and indirect uses of “theory” in anything involving critical thinking was a game changer, a way to bring students into the 21st Century, step by step. Considering the impact it has had on my teaching and scholarship, I concluded that theory had really not “gone” anywhere. It has been somewhat muted following the attacks on September 11, and it was blamed, even, for throwing the world into a dangerous relativism—all because it has been consistently misunderstood and misused. So I decided to go back to some ideas I had explored in my doctoral years, and take another look at my dissertation to see if it could help me understand some of the events that happened in the first decade and a half of this century. I can say, then, that some of the book is over ten years old, while other parts were generated about three years ago and some were written after the 2016 election.

What I am hoping to achieve with it is find (and offer) a new usefulness for literary theory, namely by channeling some ideas that have practically preoccupied me most of my life, such as the nature of Oz’ wizard behind the curtain, the illusory nature of identity, the game of our participation in the social world, and most importantly the destructive potential of a set of identity markers that are in the end constructed within our social world. This does not have to be a denial of one’s faith or morality, or a denial biological determinism (just because we say identity is constructed). All that I am trying to address is how we internalize identity as something flawed, “fallen” before we are even able to decide who we are or what we want to be. There is something “out there” in language, in the social fabric, that tells us that we can only have an identity insofar as we patch up something broken (either broken by us directly, or by those who passed down to us our fallen identity as a social inheritance). My book begs the question: why do we have to start from a fallen place? Is there no other way to relate to others, or to have a basis for relating that is not dependent on some form of judgment?

JDH: What inspired you to write about this particular theoretical focus? How is your critical approach distinct from other contemporary American scholarship?

LVA: Frankly, the initial inspiration was my encounter with Melville’s Billy Budd, Sailor. I recognized in that novella a trajectory of “falling” into language that mirrored certain obsessions I had at the time (some years ago), related to how I felt the concept of innocence to be a violent one. What I mean is that innocence is a concept that forces individuals that are identified with it (by others) to have no choice but to see themselves as fallen, as it is impossible to identify oneself as innocent. I saw Billy Budd as a doomed character who struggled to be part of language and was pressured to belong to it, which cost him his life. From there, I started to see many connections between other concepts I saw as violent, even though to others they appeared as desirable and quite positive: authenticity is a pretty popular one, and meaning is another. I wanted to look at different time periods and pinpoint the different types of social shaming that pushes individuals toward expected identities. It’s more than talking about conforming—the individual is already assumed to have failed, and can only build an identity by trying to “fix” this fallen state.

The fun part of writing this study of falling was working with some concepts taken from Jacques Derrida, some from Jacques Lacan, Martin Heidegger, Francois Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard, and many others, to help me shape an original theory of the Fall as a dangerous way to construct identity. I also wanted to find out if there is another way to reach identity, one that allows us to accept others’ identities as well. With this tool, I then proceeded to analyze one text from Melville, one from Faulkner, one from Pynchon, one from Toni Morrison and one from Rudolfo Anaya.

JDH: What are your thoughts on the current state of literary fiction and novels in America and elsewhere?

LVA: I think literary fiction is benefitting heavily from the migration of what used to be called “the margins” toward “the center,” to the point that the 21st Century has so far been a search for the fertile territory of otherness and of shifting identity: the transnational, the stateless, the transgender and fluid-gendered, the a-religious, and so on, which are now more relevant in literature than the self-identical, the traditional (even in terms of set patterns of storytelling). There is a search for new ethical perspectives as well, as I notice that many writers struggle to redefine what makes a character worthy of being written, or having a viable story to tell. I think the postmodern esthetic has become outdated, and its ambiguity or perceived moral relativism is now seen as a liability, so that much of the literature today is in search for new ways to define its purpose. Animal ethics comes to mind, with a writer such as Cormac McCarthy turning to animals for answers about what is redeemable about us, humans, when our human society no longer seems able to sustain its claim to moral superiority in the age of species annihilation and man-made global warming.

In the post-9/11 world, there is a new need for new ways to look at war (the brutal poetry of Kevin Powers’ novel The Yellow Birds comes to mind, and Aleksandar Hemon’s Bosnian account), at global, post-colonial and post-immigrant communities (J.M. Coetzee, Junot Diaz, Joseph O’neil, Roberto Bolano), as well as turning to neo-humanism to reject totalitarian mindsets in the new millennium and blurring the lines between literary genres (Lidia Yuknavitch, Haruki Murakami, Chuck Palahniuk).

JDH: You’re also a fiction writer. How do the writers and works you discuss in The Fall of Literary Theory inform your creative projects?

LVA: Given that I have long claimed Faulkner to be a literary mentor, and now I make the same claim about the closest inheritor of the genius of Faulkner’s style, Cormac McCarthy, my own literary writing leans less toward economy and more toward figurative and introspective unpacking. I do, also, think there is still room for some of postmodernists’ playfulness in contemporary fiction, which is why Pynchon is an inspiration as well, while from Toni Morrison I hope to emulate the way in which she redefines “feminine” prose through strength rather than stereotypical sensibility.

JDH: What are you working on now?

LVA: I have several projects I am working on, the most urgent, to my mind, is a novel set in communist Romania, which is the world in which I grew up (though I explore the past as well). I have let it sit for some time after writing several chapters, because I wanted to publish The Fall of Literary Theory before returning to the novel. I am in the planning stages of a book on animal ethics (in a deconstructive vein), following a few hints that Derrida gave us toward the end of his life. In his ten hour address, “The Animal that therefore I Am,” he expressed a hope that his followers would explore further this branch of deconstruction, which he would have liked to explore himself, but he knew his time was running out.

JDH: Excellent topics! I look forward to reading more of your work in the future, and best of luck with your release of The Fall of Literary Theory in December 2017.

Joseph D Haske

Joseph D. Haske is a writer, critic and scholar, whose debut novel, North Dixie Highway, was released in October 2013. His fiction appears in journals such as Boulevard, Fiction International, the Texas Review, the Four-Way Review, Pleiades, and in the Chicago Tribune‘s literary supplement, Printers Row. His poetry and fiction are also featured in various anthologies as well as in French, Romanian and Canadian publications. Haske edits various literary venues, including Sleipnir and American Book Review. He is professor of English at South Texas College.