Thinking of Ireland and Edna O’Brien

In May, as Ireland voted to end its ban on abortion, I thought back to the Ireland of my youth and to Edna O’Brien, the Irish-born novelist whose vivid and unself-conscious description of sexuality shocked her native land.

In May, as Ireland voted to end its ban on abortion, I thought back to the Ireland of my youth and to Edna O’Brien, the Irish-born novelist whose vivid and unself-conscious description of sexuality shocked her native land.

When I was twenty-one, I traveled from New York to Europe with a college friend. The last week of the trip was the most exciting and the most terrifying for her. We were to visit her extended family in Ireland and meet her boyfriend from home, who was on vacation with his family. She worried that the garda, the Irish police, would somehow find the birth control pills she’d hidden in her purse, or the hotel wardens would catch her and her boyfriend sharing a bed. The pill was illegal in Ireland then, and premarital sex was such an affront to Irish propriety that it might as well have been.

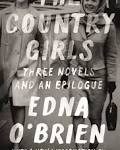

Our trip was more than ten years after publication of Edna O’Brien’s first book, The Country Girls (1960), but from our vantage point, Ireland was still the zipped, buttoned, and closeted country that greeted O’Brien’s writing with outrage and censorship.

The Country Girls together with its sequels, The Lonely Girl (1962) and Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964), tells the story of childhood friends Caithleen and Baba. Although very different, the girls are best friends and rely on one another. Caithleen is intelligent and artsy, and Baba is outgoing, brash, and impetuous. When they are sent to a stifling convent school, they connive to be expelled so they can leave their drab homes for life in the big city.

Writing the novel from her self-imposed exile in England, O’Brien depicts the friends’ high spirits and passion for exploring independence, romance, and sexual pleasures in precise, vivid, and eloquent prose. Caithleen, the narrator, says:

“I was not sorry to be leaving the old village. It was dead and tired and old and crumbling and falling down. The shops needed paint and there seemed to be fewer geraniums in the upstairs windows than there had been when I was a child.”

Baba’s father sends her to Dublin to take a commercial course, and Caithleen gets a job in a grocery store so she can go with her. Once on the train to Dublin, they look for a smoking car:

“[We] went down the corridor, giggling and giving strangers the ‘So what’ look. I suppose it was then we began that phase of our lives as the giddy country girls brazening the big city. People looked at us and then looked away again, as though they had just discovered that we were naked or something. But we didn’t care. We were young and, we thought, pretty.”

Caithleen reports her memories with keen attention to what her younger self felt and thought. She doesn’t analyze or take advantage of hindsight. There is an immediacy as well as an urgency that can leave the reader breathless. In a hotel bar they meet Henry and Reginald, two middle-aged men.

“‘You know, I understand you,’ Harry said, moving his chair closer to mine. I was uneasy with him. Apart from despising him, I felt he was the kind of man who would get in a huff if you neglected to pass him the peas. I decided to drink, and drink, and drink, until I was very drunk….”

You want to scream at Caithleen to leave, but this is a coming-of-age story and she has to learn from her foolish mistakes. She gets in a car with Harry, Babs, and Reginald, thinking the men are taking them home.

” ‘Sit close to me, will you?’ Harry said in an exasperated way. As if I ought to know the price of a good dinner. Obediently I sat near him. …

“ ‘Closer,’ he said. The way he spoke, you’d think I was a dog.”

O’Brien’s honest depiction of young women’s willfulness and sexuality shocked Irish readers, particularly in her parents’ town in County Clare. To no one’s surprised, the Irish Censorship Board banned The Country Girls and several of O’Brien’s other novels. Publicly scorned, the books were often privately devoured.

O’Brien’s honest depiction of young women’s willfulness and sexuality shocked Irish readers, particularly in her parents’ town in County Clare. To no one’s surprised, the Irish Censorship Board banned The Country Girls and several of O’Brien’s other novels. Publicly scorned, the books were often privately devoured.

A caller to a radio program told Edna O’Brien that he remembers finding a copy of “O’Brien’s dirty book” under his mother’s mattress sometime in the 1960s. “There were more Country Girls under mattresses,” she said, “than there were mattresses.”

Today’s readers are sure to wonder what so enraged Ireland about The Country Girls — that its characters were human?

O’Brien’s ability to express the human quality is sheer genius. The novelist Eimear McBride wrote of her, “Beyond all the tales and tellings of how the novels came into being and then made their progress throughout the world, they are a work of art. Sometimes painful, often funny, O’Brien lifted the linguistic play she so loved in Joyce and, taking note of his relish in the interchange of the high and low in human nature, went away and fashioned something wholly her own.”

Today’s Ireland is a world apart from the stultifying country it had been. The vote on abortion is evidence enough of that. But in the literary sphere there are changes, too. O’Brien received the Irish PEN Award in 2001, the first of several awards from her native country.

Now eighty-seven, with seventeen published novels as well as short stories, plays, poems, nonfiction, and a memoir, O’Brien continues to write and to surprise, but Ireland is rarely far away.

Her recent novel, The Little Red Chairs (2016), begins in a small village in Ireland with the arrival of an escaped Bosnian Serb war criminal, modeled on Radovan Karadžić. As the novel evolves, our interest turns to a woman who is victimized by him.

Her forthcoming novel is inspired by reports of the Boko Haram kidnappings of school girls in Nigeria, but I expect she’ll work Ireland in somewhere.

We can be sure that O’Brien will write with vivid honesty, showing us the world around us that we may not want to see.

Janet Willen

Janet Willen is author of Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery (2015) and Five Thousand Years of Slavery (2011), written with Marjorie Gann and published by Tundra Books. Publishers Weekly called Speak a Word for Freedom an “engrossing study of female abolitionists from the 18th century to the present day” and gave the book a starred review. Five Thousand Years of Slavery was named a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association and a Silver Winner in young adult nonfiction of ForeWord Reviews, and it received a starred review from School Library Journal. A writer and editor for more than thirty years, Janet has written many magazine articles and has edited books for elementary school children as well as academic texts and a remedial writing curriculum for postsecondary students. Janet lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.