On V.S. Naipaul–Do Novelists Need to be Nice?

Sir Vidia, the great Trinidad-born, British novelist and

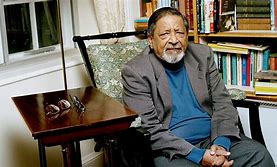

Sir Vidia, the great Trinidad-born, British novelist and travel writer is dead. You know he won the Nobel Prize, and the Booker, and I assume you’ve read his work. I admired it without loving it, but its importance is unquestionable: he’s one of the most influential of post-colonial writers. Paul Theroux, Sir Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis all owe him debts. I don’t know his entire oeuvre, so I’ll mention only his books that I do: A House for Mr. Biswas, A Bend in the River, and The Enigma of Arrival. More knowledgeable critics than I have eulogised his work, so I needn’t do so here. What I want to talk about is what you’ve also heard: that he was a cad and a rotter, to use the sort of quaint Edwardian terms his father might have used. And he never denied that. He admitted to being chronically unfaithful to his first wife, to being ‘a great prostitute man’ as well as having long-standing affairs, and his lover of twenty-five years, Margaret Murray, accused him of physical abuse too. He considers it likely that he ‘killed’ his first wife, Patricia, so painful was it for her to live with him. What’s more, and perhaps ironically for a non-white person from a British colony—which Trinidad and Tobago was until 1962, when he was thirty—he’s frequently been accused of racism, for instance by Edward Said and Derek Walcott, who said he had a ‘visceral aversion to Negroes.’ Misogynist, racist, and conservative (although he never admitted to that)—why should anyone read him?

travel writer is dead. You know he won the Nobel Prize, and the Booker, and I assume you’ve read his work. I admired it without loving it, but its importance is unquestionable: he’s one of the most influential of post-colonial writers. Paul Theroux, Sir Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis all owe him debts. I don’t know his entire oeuvre, so I’ll mention only his books that I do: A House for Mr. Biswas, A Bend in the River, and The Enigma of Arrival. More knowledgeable critics than I have eulogised his work, so I needn’t do so here. What I want to talk about is what you’ve also heard: that he was a cad and a rotter, to use the sort of quaint Edwardian terms his father might have used. And he never denied that. He admitted to being chronically unfaithful to his first wife, to being ‘a great prostitute man’ as well as having long-standing affairs, and his lover of twenty-five years, Margaret Murray, accused him of physical abuse too. He considers it likely that he ‘killed’ his first wife, Patricia, so painful was it for her to live with him. What’s more, and perhaps ironically for a non-white person from a British colony—which Trinidad and Tobago was until 1962, when he was thirty—he’s frequently been accused of racism, for instance by Edward Said and Derek Walcott, who said he had a ‘visceral aversion to Negroes.’ Misogynist, racist, and conservative (although he never admitted to that)—why should anyone read him?

Or, to put it more plainly, why should anyone read him now, in this politically-correct age, this MeToo age, this age when film people’s work is judged by the behaviour of the artists—why not writers too?

When I taught Creative Writing at a US university, I had a colleague whose emails’ signature included the following epigraph: “The words of the tongue should have three gatekeepers: Is it true? Is it kind? Is it Necessary?” Arabian Proverb (sic). Leaving aside a couple of bloopers here—the superfluous upper-case ‘N’, the incorrect attribution (it appears that in fact this much-reproduced ‘proverb’ was invented by an English clergyman in the Victorian period, but that’s not so sexy), and whether the colleague herself managed to live up to her own ethical principle, let’s consider each of three propositions it recommends.

First, when we make a statement, it should be true. In the literal sense, that’s impossible in fiction, but one could argue, as John Dufresne and others have done, that fiction is ‘the lie that tells the truth’: that the fiction writer may not tell the truth, but he (or she) tells The Truth. As for the ethics of telling the truth rather than deceiving people outside literature, this is not the appropriate place to discuss that, but I will concede, for the purposes of this essay, that truth is to be preferred over deception as a general rule, not only for the sake of humankind, but for oneself too, since a known liar is not likely to flourish for long. In short, I agree with this one. How about ‘Is it kind?’ though?

The problem here is plain: that honesty is often in conflict with kindness. To restrict our examples to the literary sphere, if you ask me for an opinion on your novel, and I consider it awful, I am unable to tell the truth and be kind. I can do my utmost to soften the blow, with caveats like ‘Of course it’s just my opinion’, or ‘although I did find much that was admirable in it’, but in the end, I can’t do both. And I would argue Sir Vidia, in his fiction and non-fiction, gave us the plain truth as he saw it, however offensive he knew that might be (and certainly he was at least as critical of newly-independent Africans as he was of their recent colonial masters).

The solution to the dilemma, perhaps, is in the third implied precept—tell the truth (the unpalatable truth) only if it’s necessary. In that case, we might argue, even if it’s not particularly kind, we should not desist. Naipaul would have argued, I think, that what he was writing about—the colonial and post-colonial world—was of such importance for all of us, that he was compelled to tell all the truth about it, even if that offended liberal sensibilities, and the sensibilities of non-white people and women. (He once declared that he could always tell if an author was male or female within a page or two, and invariably felt that the female’s writing was ‘inferior’ to his own.) The reader trusts Naipaul as a narrator, not only because of the precision of his prose—he’s widely considered the greatest stylist in English of the late twentieth century—but also because his portraits of everyone are so unflattering and unsentimental. (Although he was accused of being an ‘Uncle Tom’, he can be just as savage about white English people, especially the uneducated, whose attitude he characterises as servile, in The Enigma of Arrival. The Wiltshire workers who did jobs for him treated him with the respect and deference due to the Master, he points out.)

I’m not trying to apologise for Naipaul, whom I have little doubt was an unpleasant man. What I am arguing (again, I’m afraid) is that the personality and behaviour of the writer are irrelevant to our appreciation of his work. At least they should be. This is why fascists or neo-fascists like D’Annunzio and Malaparte are still worth reading; it’s why a reactionary who beat his servants like Dostoyevsky is worth reading. I remarked to a friend on Facebook that José Saramago (who was a Marxist) was a prickly fellow, and speculated that most decent writers did seem to be prickly, to which my friend replied, ‘I’m afraid so!’

Why is that? Prophets and truth-tellers have to be disagreeable at times. Do you really want your writers to tell stories that illustrate pious platitudes? Boring! Those are Lifetime movies, not literature. In life, we probably should strive to be kind. But as writers, we should emulate Sir Vidia. Tell the truth, whether it hurts or not. And be true to yourself, whether people regard you as a bastard for it or not. Sir Vidia didn’t care–and God bless him for that.

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)