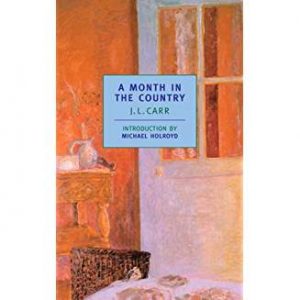

Book Review: A Month in the Country by J.L. Carr

I finished reading JL Carr’s novella (or novel, depending on your definition: it’s about 100 pages, probably 35,000 words) about two weeks ago, and have found myself thinking about it daily since. It’s not that usual for me to be so haunted by a book, so it’s prompted me to consider why. Some of you might not have read it but may be familiar with the 1987 film, which starred a very young Colin Firth and Kenneth Branagh, as well as Natasha Richardson—an unusually sensitive, faithful adaptation, of considerable power, too.

Let’s start with a synopsis and statement of theme. It’s set in the summer of 1920, in the North Riding of Yorkshire, an area I know quite well, having spent a year there in my youth, when I was unemployed and forced to live with my mother. It’s an area of moors and fells, bleak in winter, but charming in summer: very rural, and by English standards, sparsely populated. Into this land, which at the time was almost untouched by motor traffic, come two men to work at a village church, both of them ex-soldiers in the recent Great War, and both suffering from what we now call PTSD, but which was then known as shell shock, and simply dismissed, usually, as weakness and whining. Both have been hired by the vicar in order to fulfil a bequest, which requires that efforts be made by an archaeologist to find a grave belonging to one of the dead person’s medieval ancestors, and that an artist or restorer try to recover what is believed to be a medieval wall painting, long since whitewashed over. The archaeologist, who it turns out has a rather shocking secret—one that was shocking in those days, at least—is named Moon; the artist (although he refuses to call himself that) is Birkin. Both men are penurious: Moon camps in a tent in the churchyard, while Birkin bivouacs, much to the vicar’s disapproval, in the belfry. Along the way, Birkin falls in love with Alice, the vicar’s wife. But if that were not impediment enough, we learn that Birkin too is married, although his wife has run off with someone else, more than once in fact. Still, in 1920 being legally married was taken seriously.

The unusually fine, hot summer turns out to be a chance for both men to recover from their horrific experiences in Flanders, as their work, which turns out to be unusually rewarding, proves redemptive. But of course there’s more to it than that. As Birkin slowly recuperates, he’s tempted by the young vicar’s wife, who seems far too lovely and gay (in the old sense of the word) for the embittered, irritable, insensitive Revd. J.G. Keach. So there’s a classic ethical quandary that drives the narrative (along with a certain amount of suspense considering what the men will uncover in the church). Will he or won’t he?

It may sound like a nostalgic work, and unquestionably it’s an elegy to an England now departed, which J.L. Carr, who was born in 1912, must have remembered. But the background, which we’re never allowed to forget, is the senseless slaughter of the trenches. This lends the story a depth and seriousness that it might otherwise not have had. Carr asks how traumatised men can hope to be integrated into society again, and what right they may have to seek their own happiness. He also asks—a question as pertinent today, or more so today than then—how we are linked to our ancestors, and what responsibilities we bear towards them. For these reasons, although by contemporary standards it’s an undramatic, contemplative work, and indeed one which wouldn’t find a publisher nowadays, because of its length, the little book has extraordinary power. In fact it was shortlisted for the Booker—William Golding won it, for Rites of Passage—and did win the Guardian Fiction Prize. (A glance at Booker winners around that time shows how far we have fallen since then.)

But back to why this very ‘slim volume’ has had such an impact on me. Apart from the themes I’ve indicated, which I consider important, and the clarity of the prose, which is admirable, I think it’s precisely because Carr doesn’t follow ‘the rules’ for a modern novel that it’s so engaging. We all know that a novel needs a protagonist with a clear, strong desire, for a start. Birkin’s only aim at the start of the book is to prolong his employment as long as possible. Then there has to be conflict—strong opposition to the fulfilment of the protagonist’s desires. In fact there are none, unless we except a certain amount of internal struggle. There should be crises, a climax, and constant drama—show don’t tell, and all the other rubbish students are taught on creative writing courses. But in fact the true masters of the art (who most often don’t have an academic title to prove it!) don’t necessarily follow those rules. This is something like a great Japanese novel in tone—like some of the works of Kawabata, for example, in which not much happens, but a great deal is suggested and implied, and, as with Japanese pictorial art, in which much is asked of the imagination of the viewer or reader.

It strikes me that maybe we should stop writing to the formulae that the creative writing professors (the bad ones!) and the money-grubbing agents and editors insist are the path to success. Maybe we should stop painting by numbers. If we were true to ourselves, as the modest J.L. Carr was, we might just start creating great art again, as few people are doing in these days of ever-increasing conformity in fiction.

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)