Book Review: First Cosmic Velocity

Writing alternative history offers an author extra challenges beyond the normal ones presented by any other kind of historical fiction. The accepted history has to be well known in order for the reader to understand what is different and to be able to appreciate the author’s exploration of that alternative. An example of a popular alternative history in the U.S. is to imagine the results if the South had won the Civil War. Even so, the author must be a diligent researcher and make clear and crucial choices about which facts remain the same and which are turned on their heads.

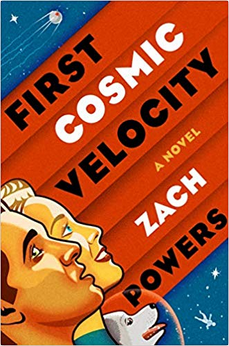

Zach Powers, whose debut novel, First Cosmic Velocity, is out from G. P. Putnam this August, meets these challenges head-on. Powers’ topic is the Soviet space program of the 1950s and ‘60s, a subject that older readers will remember with painful clarity as a blow to American pride when the Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957 and beat us into space. Later, Yuri Gagarin completed the first manned orbit of the earth in 1961, making him a worldwide phenomenon and catching the U.S. flat-footed once again.

In Powers’ alternative history, the Soviets still beat us into space, sending multiple manned missions up. The problem, for the program and the cosmonauts, is that no one knows how to bring them back down again.

The story shifts between two time periods: the story’s present day, in 1964, and 1950 in Ukraine, during a brutal, widespread drought and famine. Powers reveals the bones of his story in small steps, starting with an inspired opening: “Nadya had been the twin who was supposed to die. But she lived, and it was her sister, the other Nadya, who’d departed.”

This Nadya is watching the launch of the latest spacecraft along with the Chief Designer, the man responsible for the design of the Vostok capsule, the one that is incapable of surviving re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

In the capsule is Leonid; in fact, he is one of two Leonids. The other Leonid is secreted in a bunker in the same complex, his presence—indeed his very existence—known only to a small handful of people. To the rest of the space program and the CCCP at large, including Premier Kruschev, there is only one Leonid, as to them there was and is only one Nadya.

Yes, the Soviet engineering answer to a persistently non-performing heat shield is: twins. One trains for spaceflight, the other trains to be the gracious, charming hero to the Soviet people upon their “return” from space.

The plan certainly has limitations. Besides demanding extensive and strenuous secrecy measures and lots of set-dressing—for example, the need to pre-position a blackened, battered re-entry capsule that the unwitting recovery team drives out to collect, along with its triumphant cosmonaut—it’s impossible to manage all the variables, such as when the space-trained Nadya breaks her leg two days before the first launch, and the charm-schooled Nadya is pressed into service to take her place in the capsule.

Of the more dangerous of those variables is Ignatius, the professional propagandist assigned to the space program who materializes at inconvenient times and is clearly putting two and two together. The question is what she will do with the information once she has it.

The emotional heart of the story is laid out in the flashbacks to 1950 in Bohdan, Ukraine where the two Leonids (we never learn their given names) are being raised by their stern but devoted grandmother, who tells them the heroic stories of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, for whom their tiny, failing village is named.

As the famine worsens, Russian soldiers arrive by train to commandeer everything valuable or edible; that is when an officer takes note of the twins. It is at the point that there is truly nothing edible left to be scavenged that the next train arrives, carrying the father of the Soviet space program, Konstantin Tsiolkovski (placed here by the magic of alternative history, since he died in 1935), to take the twins for the greater glory of the Motherland.

None of the main characters here are evil or monstrous, merely trapped into the roles they’ve been assigned. In fact, most of them, in their own way, are deeply humane. The Chief Designer in particular, already bearing ugly scars from the gulag, strains under the weight of his guilt even as he continues to add to it.

Woven into the story are some magical elements that add to its other-worldly feel, such as “a possibly immortal dog,” as Powers recently noted in a discussion about the book, and a voice from space from someone who could not conceivably be there.

This is an eloquent and deeply felt narrative, the power of which builds steadily as the story unfolds. Powers’ first book, a short story collection called Gravity Changes, was the winner of the BOA Short Fiction prize, and was included in The Washington Post’s 2017 “A Summer Book List Like No Other.” Expect First Cosmic Velocity to garner significant attention of its own.

Jennifer Bort Yacovissi

Jenny Yacovissi grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, just a bit farther up the hill from Washington, D.C. Her debut novel Up the Hill to Home is a fictionalized account of her mother’s family in Washington from the Civil War to the Great Depression. In addition to writing historical and contemporary literary fiction, Jenny reviews regularly for the Washington Independent Review of Books and the Historical Novel Society. She belongs to the National Book Critic’s Circle and PEN/America. She also owns a small project management and engineering consulting firm, and enjoys gardening and being on the water. Jenny lives with her husband Jim in Crownsville, Maryland. To learn more about the families in Up the Hill to Home and see photos and artifacts from their lives, visit http://www.jbyacovissi.com/about-the-book.

- Web |

- More Posts(33)