Book Review: Hurry Up and Relax

Perhaps, like me, you’re one of those people who, finding yourself in a crowd, looks around and wonders at the individual lives of each of the people surrounding you. The tattooed barista with half-shaved/half-purple hair, the guy with the sweat-stained underarms staring into the lingerie store display, the middle-aged business man shouting into his phone as though this were still 2005.

Hard as it is to imagine, all of these people have their own history, their own movie in which they star, their own universe in which they are the omnipotent point of view.

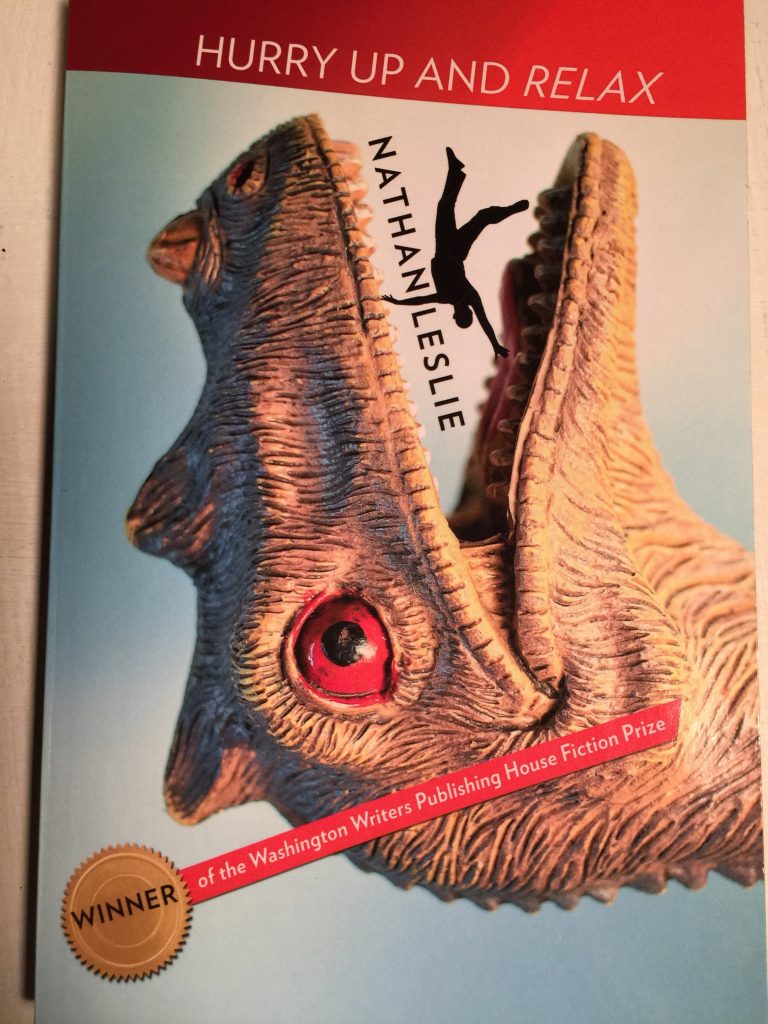

Well, Nathan Leslie imagines it. In Hurry Up and Relax—Leslie’s tenth book, coming out in October, the winner of the Washington Writers Publishing House 2019 Fiction Award—his darkly comedic eye takes in the refugees from the real estate bubble, the hostages of the gig economy, the Facebook stalkers, the Internet gamers trapped on the couch in permanent twilight.

His characters are over-educated and under-performing, ill-prepared to participate in real life. They are able to text at blinding speed but incapable of holding a job or fixing a leaky faucet. Leslie finds them in their hidden warrens and offers up their stories in closely observed detail.

In the title story, Paulie, tightly wound but hoping to take some vacay so he can hurry up and relax, is also “underwater. He bought at the height of the market, the bubbliest part of the bubble. He can never sell, not until it’s paid off twenty-three years from now.” It’s called a mortgage—death pledge—for a reason.

In “Drop”, the miserable narrator ticks off the days of living in a motel after he and his wife lose their house, after he loses his job—but at least they are out from under their mortgage. Stuffing envelopes at one cent per, he longs to take back the days of excess, the $680 dinner out just because they could. Now their friends (her friends) are the other motel residents, similar victims of the downturn: “She was a lawyer a few years back. He was an accountant. Now they do spot temp work, when they can get it.”

There’s a similar cast of characters in “Lithing Blooker Cracken” (doesn’t every horny busker con man make up his own language?), a small society of folks dumpster diving for their meals, anchored by Gus, the trust-fund guy who eats from the garbage out of a sense of guilt.

The narrator of “Rule the Day” spends evenings hanging out with his kickball buddies, nights playing Demon Warrior, and days sleeping, occasionally interrupted by his three girlfriends with whom he rarely has the energy to have sex. “Gretchen’s throaty voice is intertwining with Candi’s quasi-squeak like some kind of estrogen-y DNA staircase—all bad news for me.”

In spite of it all, many of Leslie’s characters still find a bit of poetry in themselves. The tollbooth attendant of “Exact Change” considers the folks who roll through his lane. Of one driver’s car he notes, “The dashboard is sticky with dust and residue. Even the change he hands me is grimy, as if a volcano spewed ash inside his car . . . I swear, filth seems to chuff off in the wind as he drives off.” Of the woman who inquires after his state of salvation, he says, “She has one of those perfect moral smiles, as if she was blessed by Jesus himself yesterday morning.”

Two of these stories feature Internet stalkers, and the creepiest in the collection is “K”, in which a lonely man constructs an elaborate fantasy relationship with a young woman who has simply been unlucky enough to wait on him at the pet store where she works. It’s unsettling because it’s a bit too realistic in its portrayal; this is how young women end up getting murdered.

Oddly, the two most hopeful stories for me are ones that depict fathers with their daughters—“The Collector” and, yes, “Shit Flower”—for the simple reason that both men are working to do the best job they can for their children. In the world of Leslie’s ill-equipped characters, that practically makes them superheroes.

Jennifer Bort Yacovissi

Jenny Yacovissi grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, just a bit farther up the hill from Washington, D.C. Her debut novel Up the Hill to Home is a fictionalized account of her mother’s family in Washington from the Civil War to the Great Depression. In addition to writing historical and contemporary literary fiction, Jenny reviews regularly for the Washington Independent Review of Books and the Historical Novel Society. She belongs to the National Book Critic’s Circle and PEN/America. She also owns a small project management and engineering consulting firm, and enjoys gardening and being on the water. Jenny lives with her husband Jim in Crownsville, Maryland. To learn more about the families in Up the Hill to Home and see photos and artifacts from their lives, visit http://www.jbyacovissi.com/about-the-book.

- Web |

- More Posts(33)