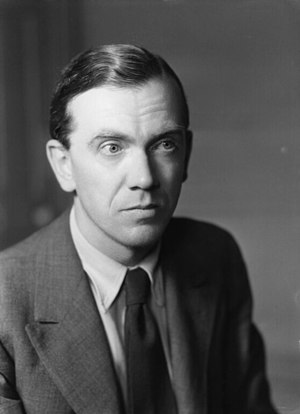

Graham Greene – A Masterclass in Fiction

‘The most accomplished living novelist in the English language,’ John Irving said of Greene before the latter’s death in 1991—and yet how many Creative Writing students, especially in North America, have even heard of him these days, let alone read him? When I taught at a US graduate program, and recommended him, I generally found that my students did not know his work, even if they had heard of him. Of course, they had been stuffed full of novels by more ‘diverse’ writers.

So I shall stick my neck out and proclaim: You can save yourself thousands of dollars, writing students. Read half a dozen of Greene’s best novels carefully, as a writer does, and it will yield you more benefit than most MFA programs, especially those of the fashionable throw-the-western-canon-out-of-window variety. Why?

First of all, because Greene was a storyteller of unparalleled skill, in spite of the plainness of his prose. (His friend and fellow Catholic novelist Evelyn Waugh described his style as ‘not specifically a literary style at all. The words are functional, devoid of sensuous attraction…’) However, he is an expert at everything else: deft characterization, setting, sharp dialogue, plot, showing rather than telling. He is one of the most cinematic of writers, and almost all of his novels, as well as some of his short stories, have been adapted for the cinema, often twice. Not only in the books he called ‘entertainments’ like Stamboul Train, The Third Man, and Our Man in Havana, but also in the ones he designated ‘novels’—that is, literary fiction—he grips the reader from the start and never lets him or her go. It is enjoyable to read a Greene novel, even when the themes are deeply serious.

And that’s the other main reason to read Greene: because whether you’re a Catholic or not (I’m not) you can’t deny that he tackles many of the biggest questions facing humanity in the twentieth century: the moral corruption of the individual, the fate of the hero’s eternal soul, the inevitability of sin, the reality of evil. Although in later years he professed to be agnostic, his religious sensibility permeates his work, as it does in so much of the best fiction we have—Dostoyevsky’s, Tolstoy’s, and Kafka’s, for example. It seems incredible that such a writer should be neglected, but so much of the best western art is being jettisoned or neglected–because of its association with ‘the patriarchy’, I suspect, usually by ignorant professors who don’t know their history. I’m not sure why Greene never got the Nobel Prize either, except that he defied easy categorization. He was a man who thought for himself, a leftist who was unafraid of criticising the left, a Catholic unafraid of portraying sinful priests and believers, a writer who saw the complexity of frailty of nearly everyone, including himself. In 1967, when he was in the final three for the Nobel Prize, the other nominees were Jorge Luis Borges and Miguel Angel Asturias, who was the winner. What a task the jury had that year! I would have cast my vote for Borges, probably, but with great sadness. Greene is not as original but he remains one of the great writers of the last century.

For readers unfamiliar with his work, where to start? The masterpieces are probably The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter, The Quiet American, The End of the Affair. Throw in The Comedians, The Human Factor, The Honorary Consul, and some of the thrillers for fun—Brighton Rock, The Third Man, and Our Man in Havana—and that’s ten novels of a more consistently high standard than anyone else I can think of writing in the past century. Incidentally, his short stories are superb too, particularly the most famous ones, The Fallen Idol and The Destructors. And I don’t think I’ve ever read a more engaging short memoir than A Sort of Life.

Greene grew up in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, less than a score of miles from where I did, and was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, in the twenties. Like Hemingway, he worked as a journalist, which influenced the plainness and efficiency of his prose; like Ian Fleming or John Le Carré, he worked for MI6, and used his experiences in espionage to great effect in his fiction (and with more seriousness than either.) My advice to young writers: read Greene now. Then read Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Powell. Your professors are not likely to have them on their syllabi, but you (and your professors) are the ones who lose by that.

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)