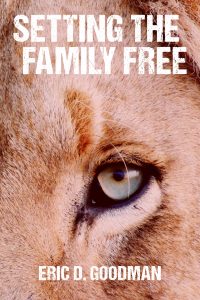

THE ENERGY BEHIND THE ROAR—AN INTERVIEW WITH ERIC D. GOODMAN, AUTHOR OF SETTING THE FAMILY FREE

When I read Eric D. Goodman’s novel Setting the Family Free, I was impressed with the themes that give the novel a memorable richness, so as I prepared to interview him, I put together questions about the ideas that resonated with me most. In his answers below, Eric expands some of my observations to include fresh themes that have even deeper meaning. Two of the most intriguing are that stories are different to almost everyone who knows them and individuals are unique to each of the people who know them. Read on to learn more about this thoughtful author and the perceptions that gave rise to Setting the Family Free.

Eric is also the author of Womb: A Novel in Utero; Tracks: A Novel in Stories, and Flightless Goose, a storybook for children. Tracks won the Gold Medal for Best Fiction in the Mid-Atlantic Region from the Independent Publishers Book Awards.

S.W. In 2011, a man in Zanesville, Ohio, actually released exotic animals from his private zoo in the same way Sammy Johnson does in Setting the Family Free. What about this event inspired you to develop it into a novel?

E.G. When the Zanesville story broke, I was fascinated by it. It’s often that a news story grabs my attention and makes me think, “This would make a good story or book.” Usually I jot down a page or so of notes and file it away for later reference. But something about this particular story entrapped me.

Imagining a preserve of dangerous animals being released into a community seemed like an unusual and exciting idea for the premise of a novel. For much of the 1990s, I lived in Ohio, and knowing that signs on the interstates near Columbus actually warned drivers that exotic animals were about seemed unreal. I had always wanted to write an animal book and always planned to set a book in Ohio. This unique situation was a way to grab two tigers by the tail in one book.

S.W. Authors always have to choose how they will tell their stories. In addition to traditional narrative, this novel includes isolated comments from characters in the story, plus newspaper and television news reports. Why did you choose this technique and what do you think it contributed to the story?

E.G. I’ve always been fascinated with perspective, and how the truth of a person or situation is seen differently by different people. In this case, I wanted to extend that idea to the story itself. That is, the same story is seen differently by different people.

I think all too often we read a quick Internet headline or watch a three-minute news report on an incident like the animal release and we immediately think we know the story: what happened, who is at fault, and why did it happen. But the story is much deeper than that, and multifaceted, and is different for different people. The story of the escaped animals is one thing to the owner, another to the neighbor who watches her horses being attacked, still another to the owner’s parent or wife or drinking buddy or the animal activist or sheriff who must hunt the animals down. And an entirely different story to those attacked or who watch their family members being attacked.

Using multiple points of view and catching the mood of those involved through short interview-like quotes helped paint parts of the story that would have been missed (or biased in a different way) through straight narrative.

What may, on the surface, seem like superficial comments by people close to the situation actually paint a deeper picture of what happened and why.

S.W. I loved the chapters that were told from the animals’ point of view. How did you capture the animals’ mindsets?

E.G. Thank you! I tried to keep those animal POV scenes short, concrete, and focused. I did a good amount of research on animals, how they perceive the world, what their motivations are. Although it was impossible to tell a story in a meaningful way without interjecting our language, I tried to make those chapters focus on the senses the way animals would sense: smell, sound, a vision that isn’t filled with human vocabulary. Readers seem to either love or hate those sections. I certainly enjoyed the challenge of writing from that perspective.

S.W. How much research did you have to do to create the animals as authentic characters? For example, you have a great description of the lioness’s roar, starting with “It begins between her ribs, where she can feel her muscles work like bellows, pushing air forward at a speed twice as fast as she can run.”

E.G. One person’s research is another person’s play. I did a good amount of research, reading articles and books, watching documentaries about animals, but much of that was really leisure. Instead of the latest Netflix series, I’d watch some animal documentaries. Instead of reading the next novel on my list, I’d read about animals. So although I probably did a lot of research, submerging myself in the subject, it didn’t feel like work—other than the fact that I’d occasionally take notes.

S.W. One of the novel’s strengths is its interweaving of numerous themes. Are there one or more themes that interested you most?

E.G. I suppose in any novel there are interweaving themes, some that the author isn’t even consciously aware of. For this book, the theme that most mattered to me was that of how a story can exist as one thing but be seen by different people as entirely different things—just as people and animals can. This is illustrated very literally by the different reporters and their angles, but also by those who chime in about the situation and key players with their opinions. I also like the theme of not only each individual being unique to each person, but how relationships between people are unique.

Sammy’s theme of love versus ego, although not put into words until late in the book, is one that I think is important to his character and why he makes the choices he makes.

Of course, there’s the obvious theme of how we as humans have managed to take ourselves out of nature, how we’ve isolated ourselves from the usual dangers of predators—which made it all the more interesting to thrust a family of predators on everyday people. Related to that: the theme of our treatment of animals, their rights to life and peace, and whether the life of an endangered species is really less valuable than that of a human in a world overpopulated and being destroyed by humans. All interesting thoughts worth exploring.

S.W. At one point, Sammy reflects that “Everybody has the capacity to love. Love in itself does not make a man good or bad, decent or indecent.” Can you talk a little about the significance of that idea in the novel?

E.G. Yes, I think that’s an interesting point. When we talk about whether a person is good or bad, we often reflect on how they treat their neighbors and families, those close to them, those they love. As well we should. But when you think about it, even people that most of us would consider bad have people and pets in their lives to love. Hitler had people around him that loved him and that he loved, he had dogs that he admired. Just because a person is able to love someone doesn’t make them good. So when we reflect on a person’s life, someone who may have had a negative influence on the world or the nation or a community, maybe reflecting on “well, he was a good husband and always helped his neighbors” isn’t a fair assessment of whether a person is or was a good person. Sammy was reflecting on the realization that he may not have been a good person despite his love for his wife and his animals.

S.W. Setting the Family Free is your second novel. You’ve also published an award-winning novel-in-stories and a children’s book. Do you have a favorite among your creations? Or a favorite fiction form?

E.G. It’s hard to pick a favorite. Often it seems the favorite is the most recent—after all that’s the one you’ve spent the most time with recently. I think it’s safe to say Setting the Family Free is my favorite of the four. At least at the moment. But I’ll always have a fond spot for Tracks, being my first book of adult fiction.

The novel seems to be the predominate form, and likely the one I’ll most often use. But I really do like the novel-in-stories, and when done well I think a good book in that format can work both as a novel and as individual stories interchangeably. In some ways, a novel like Setting the Family Free is similar to a novel-in-stories since many chapters can stand alone, and there are multiple characters telling the story. I definitely plan to return to that form. But my next few projects will be novels.

S.W. Which character in Setting the Family Free was the hardest to write? Which was the easiest? Why?

E.G. The animal perspectives were the most challenging. I wrote some pivotal scenes from the perspective of the lions, so I would put that at the top of the most difficult to write.

The easiest perspectives were probably those of the sheriff and his team of hunters. Not because hunting the animals was easy, but because their roles were clearly defined. Whether they liked their task at hand or not, they had a job to do and they had to get it done. One of the things that interested me about writing this was that these characters—demonized by some for murdering animals and glorified by others for saving human lives—seem very simple and straightforward on the surface, but are actually going through a whirlwind of emotion during their mission.

S.W. You’ve said in the past that you sometimes write for 14 hours at a time. How do you keep the creative momentum going for that long?

E.G. It’s certainly not something that happens every day. But the way I compartmentalize my writing and different aspects of my life makes it easy to work for long stretches when I’m motivated. Of course I’m getting up for coffee and water, having breakfast, lunch, and dinner during those stretches. But when I’m in the mode, I’m really there and just want to write. Contrasting that, I’ll go weeks without working on fiction, so when I get back to it I’m highly inspired, motivated, and revving to go. I get lost in the work, and before I know it, the entire day has passed and there’s still so much more I want to write.

S.W. What do you hope readers remember about Setting the Family Free?

E.G. I hope readers can relate to each of the characters by the end of the book, perhaps in ways they didn’t when they started. Part of the reason I write is to promote understanding, and to attempt getting people who see things differently to see eye-to-eye—or at least to understand one another. I’d like a reader to remember that they came to understand a character they didn’t understand at the beginning.

Also, that none of the characters exist as one true thing. They’re all syntheses of how others see them. Not good or bad, not defined by one good or bad deed, but composites of choice and circumstance and the tint of the glasses worn by those who are doing the viewing.

S.W. As a reader, what makes a story memorable for you?

E.G. There are a lot of things that can make a story memorable, but the ones that stay with me the most are stories that make me feel empathy for the character or characters. I love the moments when I finish a chapter, or a book, and think, “Yes, that’s right.” When you understand exactly why a person did what she did and warmly agree with it. A good story doesn’t have to have a heavy plot, but does need strong characters and an interesting, emotionally relatable situation.

S.W. What are you working on now?

E.G. My next novel, The Color of Jadeite, is polished and ready to share with publishers. Believe it or not, it’s written from point A to point B from one perspective! It’s a literary thriller that follows a retired government investigator turned private eye as he ventures to China in search of an artifact from the Ming dynasty. It’s sort of a “novel in settings” since it jumps from exotic locale to exotic locale.

I’m also working on a continuation of a story I wrote back when the cicadas came out in 2004. I’m hoping to finish it and have it ready to share by the time the Brood X returns in 2021. The story, “Cicadas,” was published in New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers, and I read an abridged version of it on Baltimore’s NPR station. The continuation of that story, tentatively called Wrecks and Ruins, will climax with the return of the cicadas 17 years later.

Talk about long-term planning.

But for now, my focus is on spreading the word about Setting the Family Free. I think it’s a story that a lot of readers and animal-lovers will appreciate.

Sally Whitney

Sally Whitney is the author of When Enemies Offend Thee and Surface and Shadow, available now from Pen-L Publishing, Amazon.com, and Barnesandnoble.com. When Enemies Offend Thee follows a sexual-assault victim who vows to get even on her own when her lack of evidence prevents police from charging the man who attacked her. Surface and Shadow is the story of a woman who risks her marriage and her husband’s career to find out what really happened in a wealthy man’s suspicious death.

Sally’s short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017, Main Street Rag, Kansas City Voices, Uncertain Promise, Voices from the Porch, New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers and Grow Old Along With Me—The Best Is Yet to Be, among others. The audio version of Grow Old Along With Me was a Grammy Award finalist in the Spoken Word or Nonmusical Album category. Sally’s stories have also been recognized as a finalist in The Ledge Fiction Competition and semi-finalists in the Syndicated Fiction Project and the Salem College National Literary Awards competition.

- Web |

- More Posts(67)