THE DAY I MET BETTY SMITH

Because I love reading novels and short stories, authors of fiction have always been my idols. I’ve met many of them at book signings and had the pleasure of interviewing several for this blog. For the most part, I’ve always found authors to be engaging and extremely gracious. But I’ve never been as excited about meeting an author as I was the day I met Betty Smith.

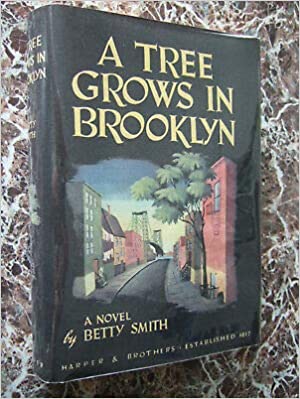

Smith’s novels were extremely popular in the mid twentieth century, although you don’t hear as much about them now. Her most famous novel, the one that earned her a place in the ranks of respected authors, is A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, published in 1943 and recently named a PBS Great American Read Top 100 Pick. She published three more novels—Tomorrow Will Be Better (1948), Maggie-Now (1958), and Joy in the Morning (1963)—but my personal involvement with Betty Smith focuses on A Tree Grows In Brooklyn, a story I still love.

Set in Brooklyn, where Smith was born in 1896, this special novel tells the story of Francie Nolan, a young girl growing up in the Williamsburg section of the city in the early 1900s. Francie is a second-generation American with an Irish father and Austrian mother. She also has a younger brother, Neely (short for Cornelius), who inherits his father’s musical talent. In addition to being a musician, however, the children’s father, Johnny, is an alcoholic, and many of the family’s struggles involve his struggles with liquor. Johnny’s also a dreamer, a trait that inspires him to make some of Francie’s dreams come true—he enrolls her in a better elementary school by lying about the family’s address—and to teach Francie that nothing is impossible.

Francie’s mother, Katie, is the rock of the family, supporting them on wages she earns as a cleaning lady. From her, Francie learns to be realistic and hard-working. The story starts when Francie is 11 years old and follows her until she graduates from high school, revealing a life of poverty’s deprivation as well as times of profound joy.

The soul of the story is its veracity and its revelations about human nature. Smith anchors it with minute details that make it immediately engaging—the appearance of an old man’s toenails, the indignity of letting the metal collector pinch Francie’s cheek so he’ll give her an extra penny for the cans she sells him, the sound her mother’s pails and mops make when she throws them into a corner on Friday afternoon. And Smith’s just as detailed about the relationship between Francie and her mother, especially Francie’s realization that Katie loves Neely more.

Smith left Brooklyn in 1919 and moved to Michigan with her boyfriend George Smith, whom she quickly married. He was a student at the University of Michigan, and although she couldn’t matriculate because she never finished high school, Smith took enough courses to earn a B.A. degree and later studied drama at Yale University. When her drama studies and her marriage ended, she and her two daughters moved to Queens, N.Y., to live with her mother. There she worked with the Federal Theatre Project as a play reader. In 1936 the Project sent her to Chapel Hill, N.C., to participate in regional theater activities.

She stayed in Chapel Hill until her death in 1972, and that is where her path crossed mine.

I was an eager 16-year-old high-school student working on a term paper about Smith for my English class when I discovered she lived only 120 miles from the small town where I grew up. I immediately saw this as a great opportunity to meet the author whose novel I loved so much.

Because those were the days before the internet, getting in touch with Smith was no easy matter. I finally learned in my library research that she had married Joseph Jones, an editor in Chapel Hill, whom I could get in touch with because of his newspaper affiliation. In response to the letter I sent him, he said he and Smith were no longer married, but he kindly sent me her home address.

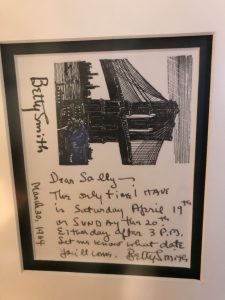

I wrote to her immediately and waited nervously until a letter from her arrived. It was only three sentences long, but it gave me a date and a time when she could see me. I still have that letter, complete with a drawing of the Brooklyn Bridge and her signature, in a frame in my study.

Three weeks later I arrived in Chapel Hill, courtesy of my parents as drivers. It was a beautiful spring day, and the first thing I noticed about Smith’s home was the large flower garden in full bloom. A black wrought-iron fence encircled the yard spreading out from a small white house. I opened the gate and started up the sidewalk when I saw a small elderly (to my young eyes, although she was only 68 years old) woman bent over some of the flowers. Guessing she might be Betty Smith, I told her who I was and why I was there. Although she seemed a little surprised, she invited me to come inside. When we reached her study, a lovely room with lots of windows and bookshelves, the first thing she did was look at her desk calendar, and that’s when I realized she really had forgotten I was coming.

But once she made sure I had an appointment, she opened up to me and treated me as a serious interviewer, even though I was obviously an inexperienced teenager. She answered all of my questions as I scribbled furiously to write down her answers. The only question I specifically remember asking her was if A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was autobiographical. I remember that question because I mispronounced autobiographical, and she corrected me. I was humiliated, but I forged on.

Even with a mispronounced word, the question was significant. One of the beauties of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is the sharpness of Smith’s memories of those times and her determination to record them. In the novel, Francie’s teacher tells her to burn her essays about her father and “poverty, starvation, and drunkenness,” and instead to write of “the true nobility of man.” In the words of a New York Times Book Review critic, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is Francie’s revenge.”

My interview with Betty Smith lasted about 20 minutes. I had brought no books for her to autograph, an omission my adult son still rebukes me for today. But Smith was not going to let me leave empty handed. “I have to give you something,” she said when I had run out of questions. She went to one of her bookshelves and removed a copy of A Tree Grown in Brooklyn translated into Italian. On the first page she wrote “For Saly [sic] Mann/ with regards/ Betty Smith.”

That book is a little the worse for wear, but it’s survived my moves to six different states since then. Along with the letter from Smith, it’s one of my favorite possessions. It will always remind me of the day a literary lion enlarged the world of an adoring teenager.

Sally Whitney

Sally Whitney is the author of When Enemies Offend Thee and Surface and Shadow, available now from Pen-L Publishing, Amazon.com, and Barnesandnoble.com. When Enemies Offend Thee follows a sexual-assault victim who vows to get even on her own when her lack of evidence prevents police from charging the man who attacked her. Surface and Shadow is the story of a woman who risks her marriage and her husband’s career to find out what really happened in a wealthy man’s suspicious death.

Sally’s short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017, Main Street Rag, Kansas City Voices, Uncertain Promise, Voices from the Porch, New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers and Grow Old Along With Me—The Best Is Yet to Be, among others. The audio version of Grow Old Along With Me was a Grammy Award finalist in the Spoken Word or Nonmusical Album category. Sally’s stories have also been recognized as a finalist in The Ledge Fiction Competition and semi-finalists in the Syndicated Fiction Project and the Salem College National Literary Awards competition.

- Web |

- More Posts(67)