“The Spirit Moves Me,” guest post of Garry Craig Powell, author of Stoning the Devil

THE SPIRIT MOVES ME

I sometimes wonder why I do it—why I write. On occasion I’m inspired and it’s fun, but if I’m honest, it’s usually a struggle. It rarely comes easy and when it’s not going well I am in a perennial state of anxiety and gloom. So why don’t I just give it up?

I tried to, but I couldn’t. So why do I do it? Certainly not for the money or the fame! The satisfaction of self-expression? Perhaps, a little. But I’ve noticed that it is much more satisfying when I don’t write autobiographically, when I rely purely on my imagination. This is not to say that I am not expressing myself when I write about fictional characters, of course—they are all, to a larger or lesser extent, projections of myself, imagined selves (a disquieting thought!) For me, though, the act of writing requires a reader, and so it can’t be purely about self-expression. It must have the purpose of communicating or sharing something with an audience. But what? After much thought, I have come to the conclusion that essentially it’s a spiritual impulse.

Don’t laugh: I don’t mean this in some naïve sermonizing kind of way. I am not out to convert you to Christianity or any other religion. When my students write stories with an overt religious message, invariably a Christian one, I tell them not to preach to me. If I want a sermon, I say, I’ll go to church. That doesn’t mean that you can’t approach complex theological matters in fiction, of course: Graham Greene, Flannery O’ Connor and Fyodor Dostoyevsky all did it, but they don’t preach to the reader. They merely present their characters to us, with their spiritual dilemmas, and allow us to make up our minds about them.

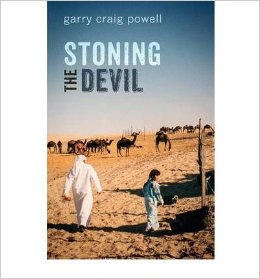

I try to do this too. In my first published book, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), I assemble a cast of characters who are mostly either irreligious or are at least questioning their religion—some of the Muslim women in the stories are beginning to reject the patriarchal values on which Islam is based (as they see it.) Others, particularly the Arab men, are ostensibly Muslims whose hypocritical behaviour shows that this is only a social façade. The one character who genuinely adheres to a religion, and lives by its tenets of compassion and selflessness, is a Theravada Buddhist, a Sri Lankan masseur named Tyrone (and incidentally the only character in the book based on a single real person.) In the main the characters, particularly the Arab women, obsess over sex and love. And what does that have to do with spirituality? Quite a lot, arguably. For although the Abrahamic religions have tended to regard sensuality as somehow opposed to true spirituality, which is supposed to be an ethereal and otherworldly phenomenon, this is only one way of looking at it. In the Far East, particularly in the traditions of Vedanta, Taoism and Zen Buddhism, non-duality is stressed—not so much as a dogma, but as something one can experience, through constant awareness. (This does not mean that the Eastern traditions are necessarily free of puritanism. They are not. But they do regard the body and soul or mind as a single entity, not two halves that are constantly at war.) And if these traditions are correct in their view that all of life, in all its manifestations, is part of a unity—the mystical vision that has been shared by Christians like St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila, not to mention the Sufi tradition of Islam—then there can be no sin in sensuality, and sex can be just as spiritual an activity as prayer or meditation.

I try to do this too. In my first published book, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), I assemble a cast of characters who are mostly either irreligious or are at least questioning their religion—some of the Muslim women in the stories are beginning to reject the patriarchal values on which Islam is based (as they see it.) Others, particularly the Arab men, are ostensibly Muslims whose hypocritical behaviour shows that this is only a social façade. The one character who genuinely adheres to a religion, and lives by its tenets of compassion and selflessness, is a Theravada Buddhist, a Sri Lankan masseur named Tyrone (and incidentally the only character in the book based on a single real person.) In the main the characters, particularly the Arab women, obsess over sex and love. And what does that have to do with spirituality? Quite a lot, arguably. For although the Abrahamic religions have tended to regard sensuality as somehow opposed to true spirituality, which is supposed to be an ethereal and otherworldly phenomenon, this is only one way of looking at it. In the Far East, particularly in the traditions of Vedanta, Taoism and Zen Buddhism, non-duality is stressed—not so much as a dogma, but as something one can experience, through constant awareness. (This does not mean that the Eastern traditions are necessarily free of puritanism. They are not. But they do regard the body and soul or mind as a single entity, not two halves that are constantly at war.) And if these traditions are correct in their view that all of life, in all its manifestations, is part of a unity—the mystical vision that has been shared by Christians like St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila, not to mention the Sufi tradition of Islam—then there can be no sin in sensuality, and sex can be just as spiritual an activity as prayer or meditation.

However, if that is the case, the sceptical reader might argue, then why doesn’t Garry Craig Powell give more edifying examples of sex in his fiction? Why doesn’t he write about Tantric Buddhism, or about the fulfilling and societally-sanctioned sex that takes place between married couples? There are a number of responses I could give to this. First of all, although I have occasionally written about healthy, happy sex, frankly it tends not to be all that interesting! If one describes it in detail, it may even read like pornography, and I have no interest in that. (Sorry!) Second, in Stoning the Devil, but also in my current project, a historical novel called The Martial Artist, about the poet, playboy, soldier and statesman Gabriele D’ Annunzio, I have tried to explore what goes wrong in people’s lives—how people who start out good (I don’t subscribe to Original Sin) so often end up making foolish decisions and immoral ones, that harm others. Nearly all the characters in Stoning the Devil, and certainly the female ones, are fundamentally decent people, even though they are not always kind and compassionate, and inflict pain on themselves and others. The Polish prostitute Kamila is a particularly pure person, deep down, for example (and no, I am not romanticizing prostitution, as you will see if you read the book). The most compelling male characters, the English professor Colin and the Lebanese banker Marwan, are also examples of people struggling, though failing, to be good. (There are a couple of really nasty men in the book, Badria’s brother, Sultan, and her father. It could be argued that one of the weaknesses of the work is their two-dimensionality.) So what I hope to do is show exactly how people ‘fall from grace’ to use the language of Christian theology. I try to illuminate some murky corners of the world, particularly in the Middle East, so that readers can come to their own conclusions about what sort of ethical choices the characters could have or should have made.

But finally, there is a third reason that my stories have hitherto been about sinners rather than saints, and have dealt with rather depressing sexual politics: that is, because I am not a fully enlightened being myself. My writing has been an attempt to explore issues that fascinate me: in the case of Stoning the Devil, why do men so often choose to treat women as inferiors, repressing their freedom and abusing them? Not only are the women’s lives ruined by this, but so are the men’s. They could have intimacy and love: instead all they get is sex and loneliness. Certainly these are political themes, but they are equally spiritual. Men only treat women badly—indeed any human being only treats another badly—because of the delusion that they are distinct, because of the delusion of duality. As soon as we understand that when we harm another person we are harming ourselves, we stop doing it.

The novel I’m working on now, The Martial Artist, is again a story about a delusional person, so readers in search of edifying spiritual fiction may be disappointed. A phenomenally gifted man, highly intelligent, creative, and charming, the most successful seducer of women of his time (even though, curiously, he was sexually ambiguous, even effeminate, and openly expressed his preference for women with boyish figures, women who were taller than himself, and would often play in the bedroom at being a woman, pushing his penis between his thighs), D’ Annunzio consciously sought to be a Nietzschean super-man, and in many ways succeeded. And yet, although he was the most important Italian writer of his time, the greatest lover, the most decorated war-hero, and for a time reigned in his own pirate kingdom on the Dalmatian coast—because he was a narcissist, he was trapped in solipsism. He never really loved. He came close to experiencing the plenitude of life, because of his boundless energy and self-confidence, but it always just eluded him, because he was too greedy. I regard the novel as a spiritual study, because it’s about a man who reaches for the fullest, most transcendent, fulfilment, and has to all appearances everything he needs to achieve it. Why and how does he fail? If I succeed in answering that, with luck I may throw some light on where most of us go wrong in our lives.

Will the next book finally portray a character or characters whose spiritual quest is successful? Might I write another Siddhartha? I don’t know. As I continue to become more spiritually aware, (I hope!), perhaps I will. Or I might take to writing haiku, or stop writing altogether… In the end, though, for me writing is only worthwhile if helps us transcend ourselves, become better people, and more clearly feel the glory of living in this universe.

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)