Interview with Tom Williams, author of Don’t Start Me Talkin’

11/26/14 Tom Williams has published two novels, The Mimic’s Own Voice and Don’t Start Me Talkin’. His short story collection, Among The Wild Mulattos, will appear in Spring 2015 from Texas Review Press. The Chair of English at Morehead State University, he lives in Kentucky with his wife and children.

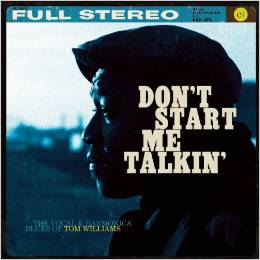

Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is a novel about Brother Ben, billed as the Last of the True Delta Bluesmen—but is he? Born in Mississippi, certainly, and purveyor of “authentic” delta blues, far from being the near-illiterate, hard-drinking, womanizing country boy he purports to be, Brother Ben turns out to be a vegetarian, Volvo-driving health fanatic, who listens to jazz for pleasure, is actually an accomplished jazz guitarist, and an extremely savvy and sophisticated manager of his own business—which he manages under his own real name, Wilton Mabry.  He is sixty-six but pretends to be nearly eighty. He drives a flashy ’76 Fleetwood Brougham between gigs. And this would all be very well were it not for the increasing dissatisfaction of his harp-playing sidekick, Silent Sam, the narrator of the novel, who is young enough to be Ben’s son and who is forced to present a persona to the world too—he also is supposed to be from Mississippi, and to be inarticulate and semi-literate, when in fact he is a college graduate from the Midwest who wears polo shirts and loafers in his private life and resents having to wear the absurd seventies pimp gear that his partner imposes on him in public. Now on their fifth tour, Sam (whose real name is Pete Owens) is tiring of maintaining the façade that their awed white audience expects of them. The dramatic tension arises from the question of whether the act can survive the tour. But along the way, with great wit and irony, Williams explores complex issues of race and identity, and cultural authenticity. It’s a terrific read—certainly one of my favourites of 2014, and probably my number one pick for fiction this year. (It’s also astoundingly cheap on Amazon.com right now.)

He is sixty-six but pretends to be nearly eighty. He drives a flashy ’76 Fleetwood Brougham between gigs. And this would all be very well were it not for the increasing dissatisfaction of his harp-playing sidekick, Silent Sam, the narrator of the novel, who is young enough to be Ben’s son and who is forced to present a persona to the world too—he also is supposed to be from Mississippi, and to be inarticulate and semi-literate, when in fact he is a college graduate from the Midwest who wears polo shirts and loafers in his private life and resents having to wear the absurd seventies pimp gear that his partner imposes on him in public. Now on their fifth tour, Sam (whose real name is Pete Owens) is tiring of maintaining the façade that their awed white audience expects of them. The dramatic tension arises from the question of whether the act can survive the tour. But along the way, with great wit and irony, Williams explores complex issues of race and identity, and cultural authenticity. It’s a terrific read—certainly one of my favourites of 2014, and probably my number one pick for fiction this year. (It’s also astoundingly cheap on Amazon.com right now.)

Garry Craig Powell: Tom, first thank you for graciously agreeing to be interviewed. I’d like to start by asking you if you’re aware of any other novels about Delta bluesmen? I’m not. I may have told you that I once considered writing one myself, but I’m really glad I didn’t! I couldn’t have anywhere close to the skill with which you’ve handled the subject, with your encyclopedic knowledge of the blues (and evident love of it), as well as your highly nuanced understanding of race in America, and your ear for African-American dialogue. Had I written a novel on this subject, it would have been full of clichés, I’m sure. And yet you have managed to avoid them, by creating these highly sophisticated, self-aware bluesmen—postmodern bluesmen, one might almost say. Can you tell us how you came up with these unforgettable characters?

Tom Williams: Well, thanks, Garry for this opportunity to talk about the book. As far as other novels, I know Walter Mosley had RL’s Dream, which is slightly about Robert Johnson, and Arthur Flowers published Another Good Lovin’ Blues and De Mojo Blues, and I can recall Toni Cade Bambarra’s fantastic story “Mississippi Ham Rider.” There’s also Gayl Jones’s great novel, Corregidora, about a female blues singer, but if any of these were on my mind during the composition of Don’t, it was subconscious.

As far as how I came up with the characters, I think that I’d break it down this way: Ben is an amalgam of every blues performer I’ve ever seen in person or on recording: John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins, in particular, with a dash of Chuck Berry and a good portion of my great-uncle Homer Jr and Ralph Ellison’s Rinehart (a character never seen in Invisible Man but the narrator of that novel assumes his identity briefly). He’d been in my mind forever—I can recall earlier versions of him showing up in apprentice stories—and then I had this distinct vision of him in a bed, his sheets billowing up like sails, surrounded by a host of acolytes. Was he dying? Or was he trying to cover something up? I asked myself these questions, wrote a paragraph to evoke that scene, and then asked who would have the best insight into the enigma that the character was.

And that led to Silent Sam/Peter Owens. He borrows a lot of my upbringing: we’re both Midwestern suburbanites; neither of us feels particularly connected to any one community (African American or otherwise); we’re both ferocious fans of the blues. But where Peter departs from me is that he can actually play a musical instrument; he’s also absent a father (a detail which has escaped many readers); and I like to think I’m a little less gullible than he is.

But as for what might make them memorable, it’s the oldest trick in the book, or so I’ve been taught to believe. Characters have to be consistent but also consistently inconsistent. Ben’s easy—he is navigating the world in a way that allows him to know who he needs to be just before someone asks him a question: he’s a chameleon. Peter/Sam is the harder one to make complex, though in the end it’s just that he is a little naïve, more than he thinks.

And, you know, ultimately, this book is a comedy, and I always borrow Jackie Gleason’s dictum that comedy is about extraordinary characters thrown into ordinary situations. Making extraordinary characters, for my money, is always easier.

Garry Craig Powell: I wasn’t aware of so many novels about the blues, though given the importance of the music in our culture, it’s not that many really. That’s an important insight too, that Peter lacks a father, and so Brother Ben becomes a father-figure to him–one he admires and feels great affection for, but also finds enigmatic, hard to figure out, and of course has to rebel against. I notice that Don’t Start Me Talkin’ shares some themes with your first novel, The Mimic’s Own Voice (Main Street Rag, 2011) http://www.mainstreetrag.com/TWilliams.html– Douglas Myles, the protagonist, a mimic of genius, is preoccupied too with how he fits into society as a person of mixed race, and who he really is, since he is so adept at adopting other voices. But in that book, brilliant as it is, I think I detect echoes of Barth and Barthelme, a cool, almost clinical irony and an obsession with language, whereas in Don’t Start Me Talkin’ it strikes me that you have truly found your own voice—no one but you could have written this, and the more transparent language as well as the greater dramatic tension you have, (since you have not just an internal conflict within the protagonist, but a subtle yet very real one with another character too) makes this book even more compelling than the first. And although this is a novel stuffed with ideas, it’s also very much a novel of character, that moves the reader as well as making him or her think. Do you see this novel as developing themes that interested you in The Mimic’s Own Voice?

Tom Williams: It’s The Mimic’s Own Voice inverted. Really. In that one, I have a nameless scholar trying his damndest to find out who the central character, Douglas Myles, really was, grappling with how that character’s role as minority, as artist, as cipher, informed his identity. And in Don’t Start Me Talkin’, I have a character thinking about many of the same things: only this time he’s the artist, or rather, the apprentice artist, learning from a master of all these matters, Brother Ben.

You know, I was asked to write a story promoting the novel; in keeping with the motif of the book as a record, we wanted to have a flip side or a bonus track for people who pre-ordered their copy. And in this short story I have a younger Sam, on his first tour with Brother Ben. Ben narrates, and the hook of the story is that the news of Douglas Myles’s death is in the newspaper, outshining the positive review of Ben and Sam’s show, and Ben wants Sam to figure out what the lesson of Douglas Myles is. Ben is thinking that he occupies the same precarious position that Myles had: never really knowing who he was, in life and on stage. But he figures out what Myles didn’t: that you have to have a sense of who you are if you’re going to be somebody else, from time to time.

So, yeah, I just admitted to be someone who repurposes his own material, essentially, but I think a good question, always, about artists and their selves is when are they at their truest? Further, The Mimic’s Own Voice is about the failures of art; it’s a terribly melancholy book. Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is about art’s triumphs. Douglas Myles can’t bring back his departed family members with his art while Silent Sam creates family with his.

Garry Craig Powell: I love the idea of the ‘bonus track’. Silent Sam aka Peter Owens makes the wry comment, “I remember from my marketing classes… that there’s no need for the genuine if your clientele believes what they’re getting is real.” On one level the novel is an indictment of the commercialisation of culture, would you agree?

Tom Williams: I wouldn’t go as far as saying it’s an indictment. I like to think that line you quoted is primarily there to underscore how much Peter is a good student; he’s listened to teachers and remembered what they said, which is what makes him the perfect apprentice for Ben.

If any cultural critique is in operation in the book it’s about how we wrongly value our artists and creators. Pete’s just as guilty of such a shortcoming: he wants the confirmation of polls and awards to tell him he’s doing something right. You mentioned something about me finding my own voice, Garry, which is parallel to what happens with Peter: throughout the book he fights against the Silent Sam persona, but ironically, as he more winds up talking and singing more, finding his own voice, albeit one that is not truly his, he becomes Silent Sam, which is just as much a contrivance as was Sonny Boy Williamson or Howlin Wolf or, yeah, Brother Ben.

Garry Craig Powell: I want to point out to readers how funny this is. When Brother Ben is chastising his partner, he tells him, “The first duty in life is to adopt a pose”. Pete recognizes it as a quote but can’t identify it. “My man Oscar Wilde,” Ben tells him laconically. You must have had a lot of fun writing this, I imagine?

Tom Williams: It’s almost an admission of guilt to say you had fun writing, isn’t it? As though every writer must be grim and sombre during the composition. But oh yeah I had fun: I learned quickly how a more picaresque plot is better suited for comedy. Each chapter had its own obstacles and personalities to create: it seemed so wonderfully inventive. Like the Wilde quote. I knew I had to smuggle that in there and lo and behold I found a spot. That chapter’s really a heavy exposition chapter too: I needed it in there after two chapters that were very in media res and pushing forward the plot. Too, when I read that passage aloud, it almost always gets a laugh, especially when Sam doubles up the joke by asking what part of Mississippi is Wilde from.

I’ll never say that writing this book was easy—that’s never the case—but I didn’t struggle; every time I needed an image or idea, I could raid the vast storehouse of blues history; every time I needed a change of pace, I could start a new chapter: a great balance of making up stuff and using what was already there for the taking.

Garry Craig Powell: You have some great dramatic crises too: the Beale Street Blues Awards, which nearly lead to a catastrophic rift between the main characters, their encounter with a rap group who have sampled their work—during which they maintain their country boy façade, interestingly, as the rappers and their manager are black too, like them—and the final show of the tour, at which the question of whether they will continue or not is resolved. On one level, there is this tension between Peter and the enigmatic Ben (whom Pete cannot quite bring himself to call Wilton, such is the older man’s power) but on a deeper one, the conflict is deep within Pete, who wonders if he is betraying himself and his mother, who brought him up to be a successful, educated, proud middle-class African-American, and then there’s the conflict—submerged, but nevertheless always present—with “all those well-meaning white folks” who “can get to a brother”. I was fascinated by this. We are no longer in the territory Ralph Ellison explores, or Toni Morrison. The white people in the novel are none of them evil; on the contrary, they are almost too respectful, too adoring. And yet they expect their bluesmen to be clichés, and that is a kind of tyranny too, isn’t it?

Tom Williams: No one has talked enough, to my mind, about these scenes and this aspect of the book, so thank you, again, Garry. But it’s what was really freeing about this book, too, knowing that I wasn’t trying to demonize anybody, that I didn’t have a specifically sociological thesis (not that Ellison or Morrison—two geniuses—had that in mind). Tyranny’s the right word, too. Peter, for instance, has such a hard time because he knows that they need those “well-meaning white folks”; one of the more painful incidents is when he sees a group of African American kids in the audience and gets excited, only to watch them rush to their white instructor to get their extra credit points for attending the concert. Yet the white characters aren’t hateful or mean. Even when they are—like my Florida cop—Brother Ben uses his prejudice against them. My favorite white character is Michael Hunt—a kind of proto-hipster who would consider himself anything but a racist, yet one who borrows freely from stereotypical black imagery to give him and his music a kind of quasi-genuineness. He’s Mick Jagger, Steven Tyler and Peter Wolf rolled into one—with Elvis sideburns. And he’s instrumental in nearly separating Pete from Ben.

This makes me think about your earlier question on the cultural critique of the novel. If I set out to have such a focus, it was always more genial than satirical. If that makes sense.

Garry Craig Powell: It does, and it’s genial in both senses of the word. But at times this aspect of the novel, the portrayal of Michael Hunt and similar characters, made me uncomfortable—and I say that as a compliment, because I think that’s the function of art. I recognize myself as one of the middle-aged white male fans. I have hung out in juke joints in Clarksdale and the hill country of North Mississippi, have swilled bad beer and eaten goat roast with the locals—much to their amusement, probably. I have been one of the tedious fans who brings along his guitar to jam with the stars. Have you ever sat in one of those jams you describe? I jammed with Corey Harris in Oxford, Mississippi. You have a ring of maybe a dozen white men—mostly overweight and bearded, as you point out—thrashing out a twelve bar blues. Most of them are OK technically, and yet the music is so formulaic when it’s done like this that it’s meaningless. You play your solo and hope you haven’t made a fool of yourself. The “real” bluesman plays his, just “phoning it in”, on automatic, and the white guys feel they have had an “authentic blues experience.” This might be a bit of a tangent, but I hope it’s relevant. What I mean is that it evokes complex emotions. I really revere a lot of the musicians who created this art form. On the other hand, I recognize that I and people like me have co-opted it, had a hand in destroying it as a meaningful form of art for black people. As you know, young African-Americans are not interested in it. And yet Heywood, Ben’s former partner, assures Pete that black folks will come back to the music eventually. Do you think so?

Tom Williams: I’ve always wondered, Garry, if the locals in Mississippi are more tolerant of Brits and other Europeans because they’re so much more polite and deferential, wouldn’t just horn in and demand to hang out on their terms.

Myself, I never sat in on a jam session, even as a witness. But I do remember some people, when I did a lot of work with the Delta Blues Symposium in Arkansas, who saw this as a key perq: getting to jam with some greats. It just seemed to me that the musicians would have to develop some act to deal with all that adoration, as Ben does, feigning weariness or playing such complicated songs that no one can keep up. Otherwise, you’d just crack one day and chase off your biggest fans.

But as for the health of the blues, there are a number of younger African American artists today, Gary Clark, Jr., Jareikus Singleton, Benjamin Booker, who are doing something new, as Mud and Sonny Boy and Wolf once did, with the blues. Those younger guys, they sound more amped up and raw, but they’ve got a blues feel and ethos. In fact, when I think of the music Silent Sam is making in the years after this novel ends, it sounds a lot like Clark, Singelton and Booker’s. (And yes, I did just drop a hint that I’d love to return to the lives of these characters.)

Garry Craig Powell: I’d like to talk about what to me is the chief paradox in the book. It’s this: although our heroes, Brother Ben and Silent Sam, are both putting on an act, pretending to be characters that are very different from their true selves, in spite of all this, when Sam has his argument with the Darnell Fuller, the rap group’s manager, he tells him, in character yet sincerely “Blues is true.” And in fact they do believe in it. Sam hates how he has to behave in order to get the music across, but he passionately believes in the blues: for him Sonny Boy Williamson is a true idol. I found this fascinating, and wondered if you see the blues as kind of metaphor for art in general. Are all artists mimics and frauds, assuming personae, and yet—the good ones at least—creating something they truly believe in?

Tom Williams: I have read aloud a number of times Brother Ben’s explanation to Sonja Hutch in Wyoming (another sample of the fun I had in the composition) about how the blues came to be. And one of the things that he says is that the first blues performer was someone who was looking for a way to “get out them fields”; in other words, the music is a dodge, an act to free one from responsibility. Yet the way to maintain the dodge is to connect with them, to say, “I got them blues too.” This is an incredible paradox: create a bond with your fellow man so you can stay away from him when you’re not performing. So, yeah, I see the bluesman as very much a metaphor for a kind of artist.

This segue is very abrupt, but I just went to the Andy Warhol Museum, in Pittsburgh, and was reflecting how Warhol was someone I knew all my conscious life—but I knew him (and once could argue how much that persona was a fiction, too) more than the art itself. He didn’t disappear into the expression. Ben is instructing Sam how to “disappear,” because what’s needed more? The blues or the blues man? Seems to me it’s the former. Same goes for art, I think. Maybe. See how I need to get back and write the second book in this series to figure out just what I’m trying to say?

Garry Craig Powell: And of course the novel explores the schizophrenia that most African-Americans have to endure, not just musicians. As Sam tells us, “most brothers had at least one voice for work and another for home… the kind my mother taught me to shape for those who’d be deciding if I could have a credit card or a college education.” I suppose this is still true, isn’t it? Do you think most African-Americans are familiar with this kind of diglossia? (And incidentally, as someone from a working class British background, it’s something I’m familiar with too.)

Tom Williams: I think you have to be. I can recall going to Cincinnati with my father, and watching his work self—he was a middle management type for the phone company—slowly dissolve as we got further and further away from home. As soon as he was in his hometown, this evolution continued in his speech where g’s got dropped, ain’t’s became more frequent, along with the occasional profanity. Conversely, as I grew up so suburban, I was the kid who had to be taught black vernacular. I got to college calling everybody “bro,” when most men of color had moved on to “cuz.” And believe me, I caught a little hell for this.

But you’re right, Garry: this phenomenon isn’t limited to African Americans. Though a development has been that African American speech can seem so much more lively, so much more—here’s that word again—genuine, when compared to Standard American English. But once I heard, second-hand, that when the novelist David Bradley was asked about the variety and malleability of African American vernacular, he said something to the effect of, “The banks cash checks written in Standard English.”

Garry Craig Powell: We should talk about the blues too, which seems to me one of least understood of musical forms, although in formal terms it’s so simple. I get tired of people saying it’s depressing and nothing but whining: haven’t they ever listened to songs like “Hoochie Coochie Man” or “Crawling King Snake”? And I loved the answer Pete gives—in his mind—to the DJ who asks the duo why they continue to sing the blues when they have become successful. The answer Pete would like to give is: “You mustn’t oversimplify the blues.” That’s true, isn’t it? The blues, it seems to me, while it expresses the pain of frustration of daily life in the segregated South, also attempts to transcend it. The great bluesmen and women have rip-roaring party songs, joyful songs, lustful songs, funny songs, boastful songs, assertive songs—it’s far from unalloyed self-pity. And your love of the blues and your sensitivity to its complexity comes through on every page.

Tom Williams: It’s funny, Garry. I know that you’re somebody who has actually turned his reverence for the form into an ability to actually play it, and play it well. I, on the other hand, cannot get my mind and body aligned to do anything more than copy the notes written out for me. I enjoy looking up the tabs for “Killing Floor,” but whenever I try to play along with the music, I cannot keep up. I have never experienced in playing a musical instrument the thrill that I knew what I needed to do before I needed to actually do it. I have encountered that thrill in sports and writing, though. And in the writing of this book, I would have to tamp down my energies to put aside the manuscript for the day. I knew that this is what I could do with blues: write about it in a way so that readers who are familiar with blues and its history would feel as though I touched upon all the right issues, while unfamiliar readers would be encouraged to go track down some of these recordings.

As I get further in time away from the book, though, I find that my affection for blues hasn’t waned one bit. Just the other day I heard, honestly, T-Bone Walker’s “Stormy Monday Blues” on the radio, and realized I had never heard it before. Heard of it, of course, and heard plenty of other versions, and heard T-Bone do some other great numbers. But that’s a terrible omission for a purported blues lover, right? Never heard T-Bone do the song he’s most synonymous with? But blues, I have found, does forgive, perhaps more than its fans do.

Garry Craig Powell: I love T-Bone’s version of that song. (And incidentally play it with my band, Slings and Arrows.) Is there anything else you’d like to tell us about the novel? I loved the book’s design by the way—square and formatted like a CD or old-fashioned LP with twelve ‘tracks’ rather than chapters, listen on a round album label. Who thought of that? Has it won any awards for design? Curbside did a fantastic job.

Tom Williams: Jacob Knabb, my editor at Curbside, asked me if I had any ideas about a cover. I said it should look like a record, which dates me. (Of note, too: I originally had in mind two empty hats as the cover image, which is not all that dissimilar from the empty chair cover of The Mimic’s Own Voice: what is my affection for empty items, I wonder?) Jacob did a photo shoot with a Chicago poet named Marvin Tate—who looks like a bluesman and is a terrific musician in his own right—and Alban Fischer did the design. They gave me exactly what I wanted, including the inside, which does resemble the old sleeves you’d get in albums. No awards yet, but the contact at McNaughton & Gunn, who printed the books, said that he was using it as evidence of the quality work that they did there.

I’ll say this about it, overall. I’m fortunate to have now two books in print, with a third on its way (a collection of stories called, AMONG THE WILD MULATTOS, due in Spring 15 from Texas Review Press): but if any of them survives, outlasts me, I’d hope it would be Don’t Start Me Talkin’, because it’s the one that, when I was done, assured me I knew what I was doing, and might have reason to continue.

Garry Craig Powell: Thank you once again for talking to me, Tom. I will be reviewing the novel in The Arkansas Review, if anyone is interested. And I recommend Don’t Stop Talkin’ for your Christmas shopping. Anyone who enjoys the blues or has any interest in African-American culture is going to love it, I guarantee.

Tom Williams: Thank you, Garry. My only regrets are that this interview didn’t transpire where it should have: over drinks while a ragged three-piece combo makes a racket all its own.

Garry Craig Powell: Next time you’re way down in Arkansas…

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)