Agnar Mykle’s Lasso Round the Moon–and a Rant against American Parochialism

Agnar Mykle’s Lasso Round the Moon—& a Rant about American Literary Parochialism

“So much of American fiction has become playful, cynical and evasive,” says novelist Joy Williams, and she goes on to deplore its “inconsequentialities”. I agree. And because I am ever more bored by the contemporary American novel, which strikes me, to add some adjectives to hers, as increasingly myopic, solipsistic and parochial, not to mention uninspired—especially the hip sacred cows like Jonathan Franzen, George Saunders, and Miranda July—I find myself ‘playing truant’ whenever I can, running for refuge to Latin America or Europe, where writers have not yet learned to turn out the MFA novel, which generally comes in one of two flavours: either flawless technically but deadly dull, dealing with domestic melodramas (Richard Russo, Jane Smiley) or else ‘quirky’, linguistically imaginative (July, Saunders, Shteyngart, Safran-Foer) and yet shallow and pretentious. Latin American writers, including the best ones, like Jorge Luís Borges and Gabriel García Márquez, break all the rules of our workshops, especially ‘show don’t tell.’ Their novels and stories are full of exposition, partly because they are ambitious; their scope is frequently immense, as in One Hundred Years of Solitude, which is nothing less than a mythologized history of a nation (and indeed a continent); and partly because the writers expect their readers to be literate, so the author is not forced to have action all the time, as if their readers had the intellectual development of adolescent boys. Instead, these writers beguile us with poetry, inundating the reader with description—not for the sake of it, not for ‘decoration’, but for what it reveals about the society and the characters observing it—and also ideas—incredible as it may seem to an Anglo-Saxon, and particularly an American reader—ideas about history, politics, and philosophy. These writers expect their readers to think and have the attention span of an adult—unlike many American authors, who write as if their audience has been brought up on comics and superheroes, which, sadly, may not be far from the truth. Faulkner once wrote as the Latin Americans do, as did Henry James, and Melville. (I am not an Americanophobe; I merely fear that this country, which has such a rich literary tradition, is committing cultural suicide.) But who are their heirs?

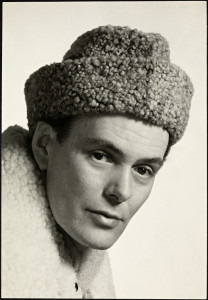

Which brings me to Lasso Round the Moon, an autobiographical or semi-autobiographical novel by the Norwegian writer Agnar Mykle, published in 1954, and now out of print in English, but still available second-hand. Like the Latin American writers, Mykle makes technical ‘mistakes’. This is what V. S. Naipaul had to say about him:

“Mykle is longwinded; he has certain rhetorical mannerisms, and his technique is clumsy. But the sensibility is true, the passion genuine. [The book] is likely to attract attention because of its frank sexual detail. But this detail is a necessary part of Mykle’s theme, which is of development and discovery; it is of a piece with the intensity and honesty of the book.”

In fact the language is nearly always fresh and original—and not merely for the sake of showing off—and the passion is unmistakable, as it is in his compatriot Knut Hamsun’s work, or the Swede Selma Lagerlöf’s. The main character is Ash Burlefoot, an intelligent twenty-year old from a stultifying family who finds himself somehow made principal of a business school in Finnmark, in the far north of the country, where he has tempestuous affairs with the insatiable Gunnhild, an older woman whom he lusts after but despises, and the sweet Siv, who is older still, but devoted to him and almost saintly in her forbearance of his neurotic moods. He manages to impregnate both women. At the time the novel was notorious for its sexual frankness—Mykle’s work is held responsible, in large part, for the open and permissive sexual climate of Scandinavia in the second half of the twentieth century—and indeed its sequel, Song of the Red Ruby, suffered a long obscenity trial. These novels focus on the hypocrisy of Norwegian society with regard to social mores, and the stuffiness of bourgeois life, but also show a young man in the process of discovering himself as he watches his erotic life, and increasingly learns to sublimate his libido and turn it into art. (By the end of Lasso, he has become a famous composer, although he still seems somewhat tormented by the guilt of having abandoned his lovers to their fates, and having cruelly tormented his little brother.)

Reviewing Mykle’s last book, Largo, a reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement noted that it ‘move(d) like some solemn, slow Scandinavian film lingering on flesh, idyllic landscape and sinful man’, which is not a bad characterization of Lasso Round the Moon, either. It is easy to poke fun at Ingmar Bergman, or Henrik Ibsen, for that matter, or Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), Hamsun or Mykle. None of these Scandinavian artists tries very hard to entertain us in the way that Hollywood movies do, or as ever-more Hollywoodesque American novels do: this is not an art of car chases and explosions, of murders and psychopaths and cheap, predictable heroics. Nor is it about loveable hipsters living their quirky, dysfunctional, but cute, funny and adorable lives. It is slow art that forces you to look carefully, and very precisely, at the transcendent moment. To compare it to painting, it is like the work of the Flemish and Dutch masters, the Breughels and Vermeer particularly, and Van Gogh too, however vastly different they may seem in terms of technique and subject matter. There is that level of intensity to it, that level of quiet penetration and illumination. It is curious that the Scandinavians, who like the English are famous for their ‘coldness’ and phlegm (unjustly in my opinion), have produced so much truly passionate art.

To judge the author by his alter ego, Mykle was a selfish and sometimes very cruel man, and Ash Burlefoot is more anti-hero than hero. Probably no American publisher would want anything to do with a novel with such a protagonist, whom most contemporary women readers would despise, and few men would identify with, or admit to identifying with. And yet the character is complex and compelling, as are the minor characters, and at the end of the novel one feels one has lived in the harsh yet grand landscapes of Norway, among the frozen fjords and the mountains, and one has longed, as only someone who does not live a self-satisfied, over-comfortable life can long, for freedom and ecstasy, self-knowledge and apotheosis.

Although Mykle boasted that he was the greatest writer in the world, he was not the most accomplished, and if we consider that Kawabata, Borges, Garcia Marquez and Milan Kundera were all writing in his heyday, we may agree that he over-valued himself. Nevertheless, Lasso Round the Moon is more full of life and passion—the real things, not the counterfeit rubbish—than almost any famous contemporary American writer’s work, literary or otherwise.

If there is one thing a young American writer should be doing, it is reading writers from outside his or her country. As Jeannette Winterson has said, American ignorance of the literature of the rest of the world is the greatest problem facing American letters today.

Garry Craig Powell

Garry Craig Powell, until 2017 professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas, was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Durham, and Arizona. Living in the Persian Gulf and teaching on the women’s campus of the National University of the United Arab Emirates inspired him to write his story collection, Stoning the Devil (Skylight Press, 2012), which was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories 2009, McSweeney’s, Nimrod, New Orleans Review, and other literary magazines. Powell lives in northern Portugal and writes full-time. His novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in 2022, and is available from their website, Amazon, and all good bookshops.

- Web |

- More Posts(79)