4/23/15 DESIREE SAFARIS

4/23/15 DAN ELDON’S DEZIREE SAFARIS

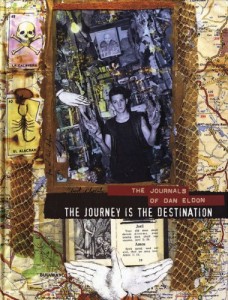

The Journey is the Destination: The Journals of Dan Eldon. Death by the will of the people. I didn’t want to write about this death, but can’t seem to put it aside. It’s been almost twelve years since Dan Eldon’s death on July 12, 1993. I first learned about it from the book of his journals which I picked up on the sale table at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Dan didn’t die in DC. He was stoned to death in Somalia, a young white man in the wrong place at a most difficult moment.

I didn’t know about Dan Eldon’s death when I opened the book. I was mesmerized by the packed and layered visual assault of the individual and collective images, whose palette, unlike the western art of my education, is somber and faded, even the yellows, reds and blues.

The images, too, were unlike the work championed by my art education. Eschatological was the word used to describe the intense crowded artwork of times past, work characterized by a fear of empty spaces, god as an unpredictable force, life as a vortex of death, hunger, and instability.

Anthropocentric was held up as the most worthy art, the gift of the Greeks and Romans, which gives humans place of pride, interpreting the world in terms of man’s values and experiences. Anthropocentric work still dominates western taste in art.

The eschatological world lives in Dan Eldon’s collages which teem with his photos, clippings from yearbooks and magazines, words, passports, drawings, paint on black and white photos, pen and ink doodles. Eschatology is not just an art concept. It’s a branch of theology relating to death, the end of the world, and the ultimate destiny of mankind. This is heavy stuff for a kid in his teens and barely beyond.

From age seven Dan’s home was mostly in Kenya where his journalist parents worked. A school assignment to make a scrapbook of a class outing to the home of the Masai resulted in what his mother calls a dazzling effect. Photos of the Masai were cut into pieces and reassembled with other scraps: “shreds of feathers, ostrich shell fragments, old coins, jewelry, beads…” Everything he’d collected was used.

The book I bought at the National Gallery of Art is titled The Journey is the Destination: The Journals of Dan Eldon. In it a visceral weight tugs on even the most playful images, like the so called Deziree Safaris. One took two Land Rovers packed with Dan, his younger sister Amy, and twelve multi-ethnic friends to a refugee camp in Malawi. Images from the trip feature youthful antics, sex-obsession, violence, fearful children, mobs, guns, fearful spear-carrying men in a cage in the dark. Beautiful white girls, beautiful black girls. “J’t’aime.” “Safari as a Way of Life.” It’s like a summer at the beach for the prep school graduates, except it’s in Africa.

Early pages in the journal show photos of Masai children. Later, there are African men with guns. The beautiful girls and boys of Deziree Safari. Glimpses of Spain, Morocco, California, New York City. Photos weighted with graffiti, paint, remarks, words and images cut from printed materials.

The pages grow more somber. Dan has photographed Africa, Arizona, New York, Japan, Marrakesh, and Moscow. More and more he’s drawn to Somalia where he and a friend from The Philadelphia Inquirer photograph the dead babies, children, men and women of a recent famine. The experience changes him. He writes, “Somalia will survive, but what kind of life is it for people that have been so wounded?”

The last photographs are unadorned: A bare-chested man with an assault rifle smoking a cigarette in front of what looks like a church with a relief sculpture of Saint Francis over the door; men and boys with guns; a thin young boy with a man in the background, head unseen, holding a tray with glasses of orange juice in front of his chest. A fork protrudes, tines upward, from one of eight glasses. It’s a menacing omen.

Afterwards I read the text. On July 12, 1993, Dan and three colleagues went to the scene of a brutal bombing by UN forces in Somalia. When the photographers began their work, the enraged crowd turned on them, stoning and beating them to death. It was the will of the people. There were no photos or videos of the event. But it was a blow to the heart.

I didn’t want to write this post about the death of a young man nearly twelve years ago in Somalia. I wanted to write about the melancholy Nocturnes by Kazuo Ishiguro whom you might know as the author of Remains of the Day. But Dan Eldon wouldn’t let me go. Next month, for sure, I’ll leave melancholy and heartbreak behind.

Dan’s mother, Kathleen Eldon, friends, and supporters organized the materials for the book, The Journey is the Destination: The Journals of Dan Eldon. Chronicle Books, San Francisco,1997.

Sonia Linebaugh

Sonia L. Linebaugh is a freelance writer and artist. Her book At the Feet of Mother Meera: The Lessons of Silence goes straight to the heart of the Westerner’s dilemma: How can we live fully as both spiritual and material beings? Sonia has written three novels and numerous short stories. She’s a past president of Maryland Writers Association, and past editor of MWA’s Pen in Hand. Her recent artist’s book is “Where Did I Think I Was Going?,” a metaphorical journey in evocative images and text.