Elena Ferrante: Italy’s Most Important Contemporary Writer

7/7/15 – Elena Ferrante: Italy’s Most Important Contemporary Writer

7/7/15 – Elena Ferrante: Italy’s Most Important Contemporary Writer

I wish I could introduce you to Elena Ferrante, but I can’t. The best I can do is make a stab at introducing you to her work. To some extent, of course, that is the case with all authors, although some writers appear so often in the media, we can be lulled into thinking we really do know them.

That is not a danger with Elena Ferrante. It’s not just that Ferrante is a pen name or that the author is reclusive. It is that she has, from the start, insisted her identity remain a mystery. When her first novel, Troubling Love, came out in 1991, she told her publisher that writing it was enough. There would be no signings, no readings, no appearances at conferences. Should it win a prize, she wouldn’t even attend the ceremony. Her letter to her published explained: “I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they won’t.”

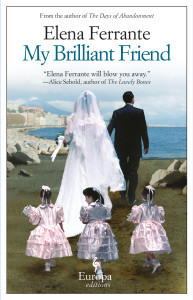

The notion that good books will find readers without an author’s promotion is one every author wants to believe, but one that no American publisher would ever go along with. But it worked for Ferrante. Her books, Troubling Love, The Days of Abandonment, The Lost Daughter, and the Neapolitan tetralogy that begins with My Brilliant Friend, have found huge audiences, first in Italy, and now that they’ve been translated into English, worldwide, making Ferrante what the New Yorker’s James Wood has called “one of Italy’s best-known, least-known contemporary writers.”

Ironically, keeping her identity a secret has fostered no end of speculation on who she may be, with much of it getting into the silly and absurd (including that her books are actually the work of another Italian author, Domenico Starnone).

None of that should matter to the serious reader because, as Ferrante believed and hoped, the books do speak for themselves, and beautifully so. The Neapolitan tetralogy traces the history of a close, lifelong friendship between two women who grew up together in a poor enclave outside Naples. They struggle to find their voice and earn a place in a culture controlled by outside forces—from abject poverty to the men who have too much say over the women in their lives. The novels are intensely personal, which may help explain Ferrante’s need for privacy. All of her narrators are women and they deal, often in shockingly candid terms, with marriage, motherhood, abuse, sexuality, and the need for independence.

Despite her reluctance to talk about her work, Ferrante did consent to be interviewed by her publishers for The Paris Review. It’s a remarkable interview, one I recommend almost as strongly as I recommend her writing, both for readers and other authors. Here are a few excerpts from that interview:

“Interviewer: James Wood and other critics have praised your writing for its sincerity. How do you define sincerity in literature? Is it something you especially value?

Ferrante: As far as I’m concerned, it’s the torment and, at the same time, the engine of every literary project. The most urgent question for a writer may seem to be, What experiences do I have as my material, what experiences do I feel able to narrate? But that’s not right. The more pressing question is, What is the word, what is the rhythm of the sentence, what tone best suits the things I know? Without the right words, without long practice in putting them together, nothing comes out alive and true. It’s not enough to say, as we increasingly do, These events truly happened, it’s my real life, the names are the real ones, I’m describing the real places where the events occurred. If the writing is inadequate, it can falsify the most honest biographical truths. Literary truth is not the truth of the biographer or the reporter, it’s not a police report or a sentence handed down by a court. It’s not even the plausibility of a well-constructed narrative. Literary truth is entirely a matter of wording and is directly proportional to the energy that one is able to impress on the sentence. And when it works, there is no stereotype or cliché of popular literature that resists it. It reanimates, revives, subjects everything to its needs.

Interviewer: How does one obtain this truth?

Ferrante: It definitely comes from a certain skill that can always be improved. But to a great extent, that energy simply appears, it happens. It feels as if parts of the brain and of your entire body, parts that have been dormant, are enlarging your consciousness, making you more sensitive. You can’t say how long it will last, you tremble at the idea that it might suddenly stop and leave you midstream. To be honest, you never know if you’ve developed the right style of writing, or if you’ve made the most out of it. . . .

Interviewer: Do you … have only one mode of writing? The question arises because quite a few Italian reviewers have attributed your books to different authors.

Ferrante: Evidently, in a world where philological education has almost completely disappeared, where critics are no longer attentive to style, the decision not to be present as an author generates ill will and this type of fantasy. The experts stare at the empty frame where the image of the author is supposed to be and they don’t have the technical tools, or, more simply, the true passion and sensitivity as readers, to fill that space with the works. So they forget that every individual work has its own story. Only the label of the name or a rigorous philological examination allows us to take for granted that the author of Dubliners is the same person who wrote Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The cultural education of any high school student should include the idea that a writer adapts depending on what he or she needs to express. Instead, most people think anyone literate can write a story. They don’t understand that a writer works hard to be flexible, to face many different trials, and without ever knowing what the outcome will be. . . .

Interviewer: When does a book seem publishable to you?

Ferrante: When it tells a story that, for a long time, unintentionally, I had pushed away, because I didn’t think I was capable of telling it, because telling it made me uncomfortable. . . .

Interviewer: Do you think this anxiety of yours has something to do with being a woman? Do you have to work harder than a male writer, just to create work that isn’t dismissed as being “for women”? Is there a difference between male and female writing?

Ferrante: I’ll answer with my own story. As a girl—twelve, thirteen years old—I was absolutely certain that a good book had to have a man as its hero, and that depressed me. That phase ended after a couple of years. At fifteen I began to write stories about brave girls who were in serious trouble. But the idea remained—indeed, it grew stronger—that the greatest narrators were men and that one had to learn to narrate like them. I devoured books at that age, and there’s no getting around it, my models were masculine. So even when I wrote stories about girls, I wanted to give the heroine a wealth of experiences, a freedom, a determination that I tried to imitate from the great novels written by men. I didn’t want to write like Madame de La Fayette or Jane Austen or the Brontës—at the time I knew very little about contemporary literature—but like Defoe or Fielding or Flaubert or Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky or even Hugo. While the models offered by women novelists were few and seemed to me for the most part thin, those of male novelists were numerous and almost always dazzling. That phase lasted a long time, until I was in my early twenties, and it left profound effects. “

Six of Ferrante’s novels are now available in English, including the Napolitano tetralogy, which were published in successive years from 2012 to 2015.

Mark Willen

Mark Willen’s novels, Hawke’s Point, Hawke’s Return, and Hawke’s Discovery, were released by Pen-L Publishing. His short stories have appeared in Corner Club Press, The Rusty Nail. and The Boiler Review. Mark is currently working on his second novel, a thriller set in a fictional town in central Maryland. Mark also writes a blog on practical, everyday ethics, Talking Ethics.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(48)