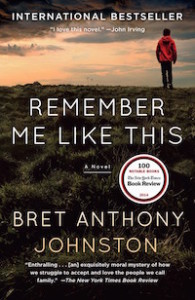

Review of Remember Me Like This by Bret Anthony Johnston

Reading Bret Anthony Johnston’s Remember Me Like This brought me back to 2003, when kidnap victim Elizabeth Smart was released after eight months in captivity. I was teaching a course in journalism ethics and I asked my students to assess the media coverage, which included 24/7 speculation about why Smart hadn’t escaped earlier and what horrors she’d been subjected to. That led to a vigorous debate over the conflict between the right to privacy and the public’s right to know. I argued that in this case there was no right to know, only prurient interest and morbid curiosity. Not everyone agreed (and certainly not cable news). If only Anthony’s novel had been available then, it would have been assigned reading. It’s the perfect answer to media callousness.

Reading Bret Anthony Johnston’s Remember Me Like This brought me back to 2003, when kidnap victim Elizabeth Smart was released after eight months in captivity. I was teaching a course in journalism ethics and I asked my students to assess the media coverage, which included 24/7 speculation about why Smart hadn’t escaped earlier and what horrors she’d been subjected to. That led to a vigorous debate over the conflict between the right to privacy and the public’s right to know. I argued that in this case there was no right to know, only prurient interest and morbid curiosity. Not everyone agreed (and certainly not cable news). If only Anthony’s novel had been available then, it would have been assigned reading. It’s the perfect answer to media callousness.

Remember Me Like This is the story of a family trying to cope with a miracle—the return of 16-year-old Justin Campbell four years after he left the house with his skateboard and did not return. The search for him has consumed the family and much of the small Texas town where they live. The family never stops looking, but their efforts are all in vain until a flea market vendor recognizes the boy and calls the police. It turns out Justin has been held all this time in nearby Corpus Christi, imprisoned by a shadowy misfit but allowed enough freedom to play with other kids. He even had a girlfriend.

Why Justin hasn’t tried to escape and what unspeakable abuse he’s been subjected remain unknown to the family and to readers. Justin doesn’t volunteer much and his parents and his younger brother Griff have been instructed by Justin’s therapist not to ask. They are all too glad to obey. More important, the author takes the same advice.

That’s because this isn’t the story of Justin’s time in captivity; it’s the story of his family trying to return their lives to normalcy in a small town where everyone knows what happens and where everyone now wants to treat Justin like a celebrity, with well-meaning acquaintances asking for his autograph (but never for details). His return isn’t the end of the story; it’s just the beginning of another one.

That’s because this isn’t the story of Justin’s time in captivity; it’s the story of his family trying to return their lives to normalcy in a small town where everyone knows what happens and where everyone now wants to treat Justin like a celebrity, with well-meaning acquaintances asking for his autograph (but never for details). His return isn’t the end of the story; it’s just the beginning of another one.

The family has a lot of work to do. It’s been shattered by the kidnapping, with mother Laura withdrawing to spend her nights monitoring an ailing dolphin, father Eric finding moments of solace in the arms of another woman, and brother Griff grappling with misplaced guilt, blaming himself because he and Justin had argued just before Justin left the house.

The family’s attempts to adjust after Justin’s return are described with remarkable sensitivity and insight. We feel for them as much now as we did when Justin was missing. They don’t know how to adjust, and at first each goes about it in his or her own way. Eric tries to get closer to Justin by teaching him how to drive, while Laura devours books on the Stockholm Syndrome, and Griff tries to prove he can be as unhappy as he thinks Justin is. While each deals with his own guilt and regrets—and they all have plenty—they must learn anew how to relate to one another because they’re all different people now, especially Justin.

Johnston, who directs the creative writing program at Harvard, has worked hard to get inside the heads of Laura, Eric, and Griff (as well as Justin’s caring grandfather), and he succeeds in intimate detail. I can’t remember a book, fiction or nonfiction, in which I came away with a better understanding of the characters’ though processes. But Johnston wisely eschews Justin’s point of view so that we, like the rest of the characters in the novel, never get more than fleeting indications of what he is thinking, feeling, or suffering.

In an interview with National Public Radio, Johnston says he intentionally kept his distance from Justin, and particularly from the details of his years in captivity:

It was a conscious move. I really didn’t include it because I wanted to respect the character. I wanted to spend most of the time on the page with his family and not with what had happened to him. I understand that the reader is going to be curious about it. But I didn’t leave it out for any kind of tactical reason. I think the information is in the book. It’s just there in small, obscure, kind of off the page ways.

At one point in the novel, Griff works up the courage to ask Justin what life was like in captivity. “Is that a clever way of asking if he raped me?” Justin responds. Griff denies it, but he knows he’s lying and hates himself for wanting to know.

As Johnston notes, readers will be curious, but like Griff, we will hate ourselves for it. I think Johnston deserves a lot of credit for knowing when to be silent. If only the media could learn the value of such restraint, life might be just a tad bit easier for other victims.

Mark Willen

Mark Willen’s novels, Hawke’s Point, Hawke’s Return, and Hawke’s Discovery, were released by Pen-L Publishing. His short stories have appeared in Corner Club Press, The Rusty Nail. and The Boiler Review. Mark is currently working on his second novel, a thriller set in a fictional town in central Maryland. Mark also writes a blog on practical, everyday ethics, Talking Ethics.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(48)