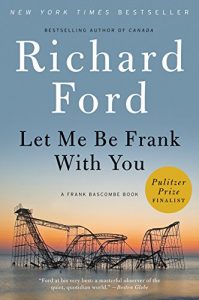

Richard Ford’s Bascombe, A Jersey Guy

As a transplanted but still loyal New Jerseyite, I was skeptical when a friend recommended Richard Ford’s book Let Me Be Frank with You as a humorous take on Hurricane Sandy. I couldn’t imagine anything funny about the storm that leveled large swaths of my former state, but I was curious to see how anyone could. While I differ with her characterization of this as a humorous take, I wholeheartedly agree with her recommendation of this book.

As a transplanted but still loyal New Jerseyite, I was skeptical when a friend recommended Richard Ford’s book Let Me Be Frank with You as a humorous take on Hurricane Sandy. I couldn’t imagine anything funny about the storm that leveled large swaths of my former state, but I was curious to see how anyone could. While I differ with her characterization of this as a humorous take, I wholeheartedly agree with her recommendation of this book.

Let Me Be Frank with You is humorous the way Chaplin’s Little Tramp was humorous, the way Larry David’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm” is humorous, and the way life is humorous. There’s artistry in blending the bitter and the sweet, and Ford is a master at it.

The book begins two weeks before Christmas 2012, eight weeks after Hurricane Sandy walloped the New Jersey Shore. Frank Bascombe, the main character and narrator, drives to the Shore to meet the man who’d bought his house there eight years earlier and to see what, if anything, survived the storm. The opening lines set the mood:

“Strange fragrances ride the twitchy, wintry air at The Shore this morning. … Flowery wreaths on an ominous sea stir expectancy in the unwary.”

“It is, of course, the bouquet of large-scale home repair and re-hab. Fresh-cut lumber, clean, white PVC, the lye-sniff of Sakrete, singing sealants, sweet tar paper, and denatured spirits.”

New Jersey has been the landscape for Ford’s three Frank Bascombe novels—The Sportswriter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Independence Day, and The Lay of the Land. Let Me Be Frank with You, which Ford calls “a Frank Bascombe Book,” is made up of four linked short stories.

In the first, “I’m Here,” we see that Bascombe’s diminished home state reflects his own mood. To him, “Life’s a matter of gradual subtraction.”

Bascombe is the same thoughtful, if acerbic and droll, man that he was in the earlier books, but he’s older and has more to ponder. He was thirty in The Sportswriter and is now sixty-eight, somewhat shrunken, just like his former house and his home state. Bascombe says little but thinks a lot. A casual acquaintance would be startled at how reflective he is.

In “I’m Here,” he walks along the beach and wonders if he’ll fall. He thinks:

“I feel a need to more consciously pick my feet up when I walk — ‘the gramps shuffle’ being the unmaskable, final-journey approach signal. It’ll also keep me from falling down and busting my ass. What is it about falling? ‘He died of a fall.’ … Is it farther to the ground than it used to be? In years gone by I’d fall on the ice, hop back up, and never think a thought. Now it’s a death sentence. … Why am I more worried about [falling] than whether there’s an afterlife?”

Bascombe describes himself as “a member of the clean-desk demographic, freed to do unalloyed good in the world, should I choose to.” He chooses to, though he doesn’t seem to realize it. The thrust of each of the four stories is the help he gives, though often begrudgingly.

In the second story, he welcomes into his current house a woman who’d lived there until she was nearly seventeen. As they talk, both unsure about whether she’ll reveal her story, she says:

“‘We seem to need to know everything, don’t we?’”

“‘You’re the history teacher,’” I said. Though of course I was violating the belief-tenet on which I’ve staked much of my life: better not to know many things. Full disclosure is the myth of the fretting classes.”

The story she finally tells is horrifying. Bascombe feels inadequate to the moment and confused about his own emotions. Somehow, unsure as he is, he finds the right words for her.

The story she finally tells is horrifying. Bascombe feels inadequate to the moment and confused about his own emotions. Somehow, unsure as he is, he finds the right words for her.

In the third story he visits an assisted-living facility to bring an orthopedic pillow to his ex-wife who’s suffering from Parkinson’s. In the final story he visits someone he knew from a Divorced Men’s Club who’s on his death bed and wants to confess to him. Both are reluctant visits.

He reads to the blind, greets veterans returning from overseas combat, and writes a monthly column called “What Makes That News?” for the We Salute You magazine that his group gives to the returning troops. The column, which he signs HLM—as in H. L. Mencken, perhaps?—illustrates that “some of the idiotic stuff in the news can be actually hilarious, so that suicide can be postponed to a later date.”

Bascombe reveals his doubts to us readers, but the other characters in the book are not privy to them or his reflections. He tells us, “we have only what we did yesterday, what we do today, and what we might still do. Plus, whatever we think about all of that.”

He’s reflective, smart, a bit cynical, and, in the main, a good man. He’d probably be surprised to hear me say that. If you read Let Me Be Frank with You or Ford’s other Bascombe books, which I also recommend, I think you’ll agree with me.

Janet Willen

Janet Willen is author of Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery (2015) and Five Thousand Years of Slavery (2011), written with Marjorie Gann and published by Tundra Books. Publishers Weekly called Speak a Word for Freedom an “engrossing study of female abolitionists from the 18th century to the present day” and gave the book a starred review. Five Thousand Years of Slavery was named a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association and a Silver Winner in young adult nonfiction of ForeWord Reviews, and it received a starred review from School Library Journal. A writer and editor for more than thirty years, Janet has written many magazine articles and has edited books for elementary school children as well as academic texts and a remedial writing curriculum for postsecondary students. Janet lives in Silver Spring, Maryland.