Katie Gilmartin, Lambda-award Blackmail, My Love

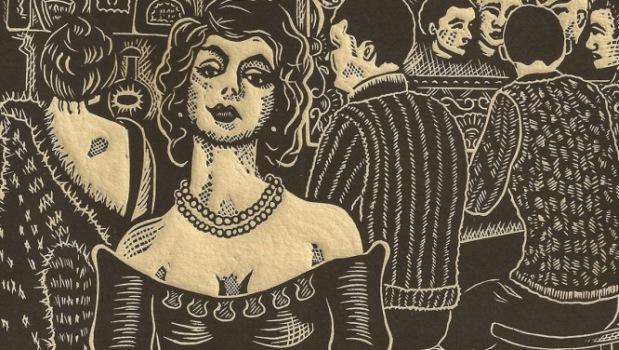

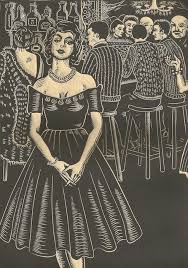

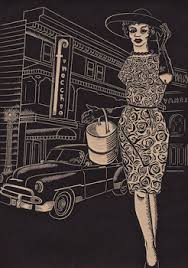

8/20/15 INTERVIEW WITH KATIE GILMARTIN, AUTHOR OF BLACKMAIL, MY LOVE In my review last month of the 2015 Lambda Award-winning mystery Blackmail, My Love, I said that as I read Gilmartin’s account of gay life under 1950s police and societal brutality, I realized she was also in effect writing about what it’s like to be a member of the wrong party under a totalitarian government, where people are persecuted for being who they are, for thinking what they think, and for wanting to meet and interact with other like-minded people. Today I have a chance to ask author Gilmartin what inspired her writing. Besides being a writer, the multi-talented Oberlin and Yale graduate, who taught cultural studies emphasizing gender, also illustrated her own novel in her present incarnation as expert on the art and craft of printing and as overseer of Chrysalis Print Studio, where she teaches linocut and monotype classes. See her blog at katiegilmartin.com .

8/20/15 INTERVIEW WITH KATIE GILMARTIN, AUTHOR OF BLACKMAIL, MY LOVE In my review last month of the 2015 Lambda Award-winning mystery Blackmail, My Love, I said that as I read Gilmartin’s account of gay life under 1950s police and societal brutality, I realized she was also in effect writing about what it’s like to be a member of the wrong party under a totalitarian government, where people are persecuted for being who they are, for thinking what they think, and for wanting to meet and interact with other like-minded people. Today I have a chance to ask author Gilmartin what inspired her writing. Besides being a writer, the multi-talented Oberlin and Yale graduate, who taught cultural studies emphasizing gender, also illustrated her own novel in her present incarnation as expert on the art and craft of printing and as overseer of Chrysalis Print Studio, where she teaches linocut and monotype classes. See her blog at katiegilmartin.com .

Question: I read on your blog that you wanted to write a book once you realized, as a child, that books didn’t simply exist but were written by people. What gave you the idea of Blackmail, My Love? How long ago? What were you doing otherwise at the time?

Answer: My graduate research involved interviewing older lesbians about their lives in the 1940s and 1950s, and I’ve been haunted by their stories ever since. Here’s one: during World War II a butch woman named “Bernie” worked at Mare Island Naval Base, about thirty miles northeast of San Francisco. Returning home from work one night, she was arrested and charged with vagrancy despite the employee identification she was wearing on her cap and jacket. The next morning a judge sentenced her to six months in prison, suspended “on condition you leave Vallejo within twenty-four hours. We don’t want your kind in California.” Back home in Wyoming, “Bernie” tried to commit suicide by driving twenty-four miles on the wrong side of the road, in the dead of night, drunk. It was such a rural area, she didn’t meet a single car – and so survived to tell me her story.

Answer: My graduate research involved interviewing older lesbians about their lives in the 1940s and 1950s, and I’ve been haunted by their stories ever since. Here’s one: during World War II a butch woman named “Bernie” worked at Mare Island Naval Base, about thirty miles northeast of San Francisco. Returning home from work one night, she was arrested and charged with vagrancy despite the employee identification she was wearing on her cap and jacket. The next morning a judge sentenced her to six months in prison, suspended “on condition you leave Vallejo within twenty-four hours. We don’t want your kind in California.” Back home in Wyoming, “Bernie” tried to commit suicide by driving twenty-four miles on the wrong side of the road, in the dead of night, drunk. It was such a rural area, she didn’t meet a single car – and so survived to tell me her story.

The 1950s were such an oppressive time for Queer people – and yet they were also a time of such creative resistance. Drag, gay slang, butch and fem styles: so much vibrant culture emerged or evolved in that crucible of fire, where going to a gay bar for an evening with friends could lose you your job, alienate you from your family forever, and land you in jail or a mental institution. I wanted to explore, through my writing, what it would have been like to believe everything they said about us then, and also, how it was possible that some of us believed none of it.

This was the era of Senator McCarthy’s “Pervert Inquiry,” when Senator Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska declared, “You can’t hardly separate homosexuals from subversives,” and Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield launched a crusade against “pornographic filth in the family mailbox” that made some recipients of mail with homoerotic content the subject of FBI surveillance. The term that dominated the era – besides, of course, the slur “Queer” – was the noun “degenerate.” That word functions also as a verb that means, literally, to decline or deteriorate, to lose physical, mental, and moral properties. Every time the word “degenerates” was used, we were reminded that we were, perhaps inevitably, coming undone – mentally, physically, spiritually, emotionally. The writing of the time certainly enforced this belief: from respectable literature to pulp fiction, by the last page Queers generally ended up dead or insane. The film industry’s Production Code more or less required that we end up dead or insane. Setting a mystery in this period, wrapped around the lives of Queer people, seemed inevitable to me: that noir atmosphere of paranoia, of being trapped in a maze with your back against the wall, the cards stacked against you, God nowhere in sight, was, in fact, real for many people.

This was the era of Senator McCarthy’s “Pervert Inquiry,” when Senator Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska declared, “You can’t hardly separate homosexuals from subversives,” and Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield launched a crusade against “pornographic filth in the family mailbox” that made some recipients of mail with homoerotic content the subject of FBI surveillance. The term that dominated the era – besides, of course, the slur “Queer” – was the noun “degenerate.” That word functions also as a verb that means, literally, to decline or deteriorate, to lose physical, mental, and moral properties. Every time the word “degenerates” was used, we were reminded that we were, perhaps inevitably, coming undone – mentally, physically, spiritually, emotionally. The writing of the time certainly enforced this belief: from respectable literature to pulp fiction, by the last page Queers generally ended up dead or insane. The film industry’s Production Code more or less required that we end up dead or insane. Setting a mystery in this period, wrapped around the lives of Queer people, seemed inevitable to me: that noir atmosphere of paranoia, of being trapped in a maze with your back against the wall, the cards stacked against you, God nowhere in sight, was, in fact, real for many people.

And then there was blackmail! Blackmail targeting Queer people flourished after World War II — anti-sodomy laws basically armed blackmailers, because at the time we couldn’t go to the police for assistance. There were extortion rings targeting Queers in New York, Atlantic City, and Washington, D.C. In the 1950s the F.B.I. used the supposed susceptibility of homosexuals to blackmail to justify hounding out and firing large numbers of us from government service.

And yet, with all that, San Francisco had more Queer bars then than it has today. Even though a few drinks with friends could land you in jail and your name in the newspaper, we flocked to bars, forming communities and identities that established the groundwork for the rights we’re claiming today. Much of our Queer slang comes from the era, terms such as “friends of Dorothy,” a code word for gay or lesbian. “Are you a friend of Dorothy?” would sound perfectly innocuous to those not in the know. “Dorothy who?” would alert you to tread carefully, while “We’re bosom buddies!” would assure you that you may have found one of your own. The phrase is such a gentle weapon of self-defense, it seems to me, crafted in the context of extreme, legally and medically sanctioned, homophobia.

The era also saw resistance in the form of gender-crossing of many kinds. A fictional character based on legendary drag performer José Sarria appears in Blackmail, My Love, performing an incendiary monologue about Alfred Kinsey at the Black Cat Cafe. The real José ran for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1961, the first openly gay candidate for public office in the U.S., and throughout his life José displayed extraordinary elegance and wit in his acts of resistance. My favorite story: in San Francisco and cities throughout the U.S., Halloween was the one night of the year when men wearing dresses were generally immune from arrest, but police cracked down at the stroke of midnight, routinely arresting “wagonloads” of men. José learned that the statute justifying these arrests prohibited “wearing clothing of the opposite sex with intent to deceive.” So he got some felt, glue, and safety pins. He cut out felt patches in the shape of a black cat, wrote the words, “I am a boy” on them, glued pins to the back, and passed them out among patrons of the Black Cat. The police backed off: protection from arrest by means of felt, glue, scissors, and safety pins.

So, I was haunted by these amazing life stories I’d been told, and inspired by the dazzling culture of resistance that developed. The narrative of Blackmail, My Love – a dyke comes to San Francisco to find her gay brother, a private dick investigating a blackmail ring targeting Queers — it somehow seemed inevitable: this was a novel that needed to be written.

Question: Categorically Blackmail, My Love is historical mystery, yet the sociological aspect takes precedence, to my mind. As I said here on Late Last Night Books last month, mysteries are plentiful, even mysteries in unique historical settings, whereas rare are books showing the effective persecution of a people—any people—to the extent that many of them are ashamed to be themselves. Was this a primary point as you began writing or did it develop as you wrote the book?

Answer: Exploring Queerdom in the fifties was definitely my primary goal, but I was less interested in making any particular point than I was in exploring the experiences, both horrific and glorious, of living through that era. How was it that some people lived lonely, tormented lives, while others found love and self-acceptance? How would these different people respond to the terror of receiving a blackmail letter in the mail? While the narrative is deeply ensconced in that particular time and place – San Francisco in the 1950s – ultimately it is the characters who need to bring that era alive. And I was deeply interested in a personal way — who would I have been if I’d lived at that time? Would I have been the big brazen butch whose bar fights carved out social space for us to find each other? Would I have been the closeted housewife who had a decades-long affair with her “best friend,” the housewife two doors down? Or would I have been too afraid to act on my desires at all? Writing Blackmail, My Love, gave me a chance to explore these possibilities, and more. What would it have been like to have been a gay man who truly believes he is destined for degeneracy? I love hearing how my readers respond to these characters. Many have told me they love him most of all — the gay man who lives the sinister depths of the period, the one who most buys into the shame and self-loathing, because we see his gorgeous humanity. Others love the sexy Lucille who parlays her curves into employment that ensures comfort and security for herself and her friends, while not relinquishing an ounce of her self-respect.

Answer: Exploring Queerdom in the fifties was definitely my primary goal, but I was less interested in making any particular point than I was in exploring the experiences, both horrific and glorious, of living through that era. How was it that some people lived lonely, tormented lives, while others found love and self-acceptance? How would these different people respond to the terror of receiving a blackmail letter in the mail? While the narrative is deeply ensconced in that particular time and place – San Francisco in the 1950s – ultimately it is the characters who need to bring that era alive. And I was deeply interested in a personal way — who would I have been if I’d lived at that time? Would I have been the big brazen butch whose bar fights carved out social space for us to find each other? Would I have been the closeted housewife who had a decades-long affair with her “best friend,” the housewife two doors down? Or would I have been too afraid to act on my desires at all? Writing Blackmail, My Love, gave me a chance to explore these possibilities, and more. What would it have been like to have been a gay man who truly believes he is destined for degeneracy? I love hearing how my readers respond to these characters. Many have told me they love him most of all — the gay man who lives the sinister depths of the period, the one who most buys into the shame and self-loathing, because we see his gorgeous humanity. Others love the sexy Lucille who parlays her curves into employment that ensures comfort and security for herself and her friends, while not relinquishing an ounce of her self-respect.

For me, the sociological or historical context provided a fascinating framework in which the narrative could unfold. For example, Queer bars of the era were subject to ongoing harassment – raids, demands for protection money from the police, violence, and so forth. But in a little-known case, the California Supreme Court ruled in 1951 that bars could not be shut down solely because homosexuals gathered there. Sol Stoumen, the heterosexual owner of the legendary Black Cat Cafe, initiated the case when the Board of Equalization suspended his liquor license because the cafe was “a hangout for persons of homosexual tendencies.” While Stoumen initially denied the charge, he hired a lawyer who shifted the focus of the case to civil rights, arguing that homosexuals, too, have a constitutional right to public assembly. The San Francisco Superior Court and the First District Court of Appeals denied this right, but the California Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. In their decision they cite an Oklahoma ruling in which prostitutes were classified as human beings and therefore entitled to such basic human rights as food and shelter, as long as it was not provided for immoral or illegal purposes. Having affirmed that homosexuals are human beings, the court ordered the Black Cat’s liquor license restored.

What happened, of course, was that the police came up with new tactics for surveillance. They focused on the fact that, if they could identify criminal activity, they could raid the bars. So bartenders became de facto chaperones, trying to ensure that patrons didn’t do anything that could be construed as illegal. The police focused on identifying – and in many cases instigating – illegal acts such as same-sex dancing, or even a man placing his hand on the knee of another man. They trained their youngest officers and agents to affect “homosexual mannerisms” and to “come on” to bar patrons in order to produce evidence of criminal activity. This all works its way into the mystery in Blackmail, My Love – and the characters figure out creative ways to fight back.

Question: Are you writing—do you feel the desire to write—a next book? Is there more you want to say about the history of gay suppression and repression or are you thinking about, or already writing on, another topic?

Answer: At the moment I’m working on a short story. I’ve been invited to contribute to Oakland Noir, part of a great series of noir stories published by Akashic Books and set in various cities – New York, Chicago, New Orleans, London, Moscow, Helsinki, Havana, and so forth. My story will be set a little later in the fifties than Blackmail, My Love, in the Bushrod neighborhood of Oakland, home to The White Horse, reportedly the oldest gay bar in the country still in operation. I’ll definitely be writing another novel: writing is just too much fun to stop. I love having some thorny question to chew on as I’m driving to the dentist or pulling weeds in my garden. What kind of conversation would these two characters have if they met? Or, now that my main character has broken into the home of the Chief of Police to find evidence, and now that he’s walking down the hall about to catch her in his den, how am I going to get her out of there alive? I had to chew on that for a week – and then suddenly the answer appeared. Everything seems obvious in retrospect!

Question: Because of gender roles, more than once I’ve suspected that sexual and domestic relationships are simpler between two women or two men than between a woman and a man. As a scholar of gender studies, what do you think?

Answer: There’s so much mysterious alchemy involved when two personalities, two lives collide. Individuals inhabit genders in so many different ways: comfortably, uncomfortably, in between, outside, expansively, in resistance. I think that when it comes to relationships, it is hard to generalize: everything depends on the two individuals involved.

Question: Do you read historical fiction? Mysteries? Tell us about a few of your favorite books and authors.

Answer: I’m a pretty voracious reader, especially of fiction from the fifties – trashy pulps as well as literature with a capital “L.” Raymond Chandler, Chester Himes, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith. I recently re-read Ann Bannon’s Beebo Brinker. I also enjoy Sarah Waters’ historical writing – Night Watch, for instance, set in World War II, a narrative that moves backward in time yet manages to sustain suspense. I love Alison Bechdel’s graphic novels – the great community work she did in her various Dykes to Watch Out For books, and the intriguing investigation of her father’s life in Fun Home.

I read a great deal of nonfiction history, as well – books on police procedure in the fifties, for example, or One Magazine, an early homophile publication. Justin Spring’s Secret Historian, about the life of Samuel Steward, is a very readable history book. Steward was an apparently mild-mannered professor by day, and a sex renegade by night – he had lots and lots of erotic encounters, many of them anonymous, some of them paid for, some in groups, some solo – every kind of erotic encounter you could imagine, except one ensconced in a long-term monogamous relationship (which he disdained – but that’s another story). Later Steward wrote some of the earliest trashy gay pulp novels, and became official tattoo artist of the Oakland Hell’s Angels.

He knew all kinds of people – he gave Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas a Mix Master, which they adored. He and Alfred Kinsey became good friends, because they were both obsessed with sex, and obsessed with record-keeping and categorization. Steward provided a lot of information to the Kinsey Institute, and might have worked for them except that at the time you were required to be “demonstrably heterosexual” in order to be hired there. He was extraordinarily brazen, and extraordinarily fortunate in getting away with it. He’d write a letter to a friend, for example, and then add some homoerotic illustration over the top. Suddenly putting that letter in the mail could put him in the jail – and the FBI on the trail of its sender and recipient.

Steward kept a record of all of his erotic encounters, what he called his Stud File: a huge box of index cards on which were written (in code) details of each of his many, many erotic encounters, including the activities they engaged in, his playmate’s “accessories,” etc. In the back of the file was a clipping, from a Texas newspaper, which gave an account of a woman there who was sentenced to jail time based on an erotic diary she kept: a diary. I love the fact that Steward kept this clipping at the back of his stud file: it’s like he was telling us that he knew exactly how dangerous it was to live his life the way he did, and that he was living it anyway.

Gary Garth McCann

First-prize winner for short works and for suspense/mystery, Maryland Writers’ Association, Gary Garth McCann is the author of the novella Young and in Love? and of the novels The Shape of the Earth and The Man Who Asked To Be Killed, praised at the Washington Independent Review of Books. His most recent published stories are available online in Chelsea Station Magazine, Erotic Review Magazine, and in Mobius: The Journal of Social Change. His other stories appear in The Q Review, reprinted in Off the Rocks, in Best Gay Love Stories 2005, and in the Harrington Gay Men’s Fiction Quarterly. See his blogs at garygarthmccann.com and streamlinermemories.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(57)