WHERE GO THE BOOKS?

3-04-2016 – WHERE GO THE BOOKS?

No one was more surprised than me—a self-confessed book hoarder—when I let stack upon stack of books go free from my home. It all started when my 20-something daughter, packing up her childhood room, confronted me with a hallway of books that had lost their shelving status. My chance for redemption had at last arrived.

Two years ago I wrote about how painful it was for me to give away books, and how all my life I’ve defined myself by my books (My Burdens, Myself: Why I Can’t Give Away Books). To a large extent I still feel this way. And yet, as much as my self-esteem is in direct proportion to the number of books in my home, I found it oddly simple to let most of my daughter’s books go, although I appreciated that she gave me a say in the matter.

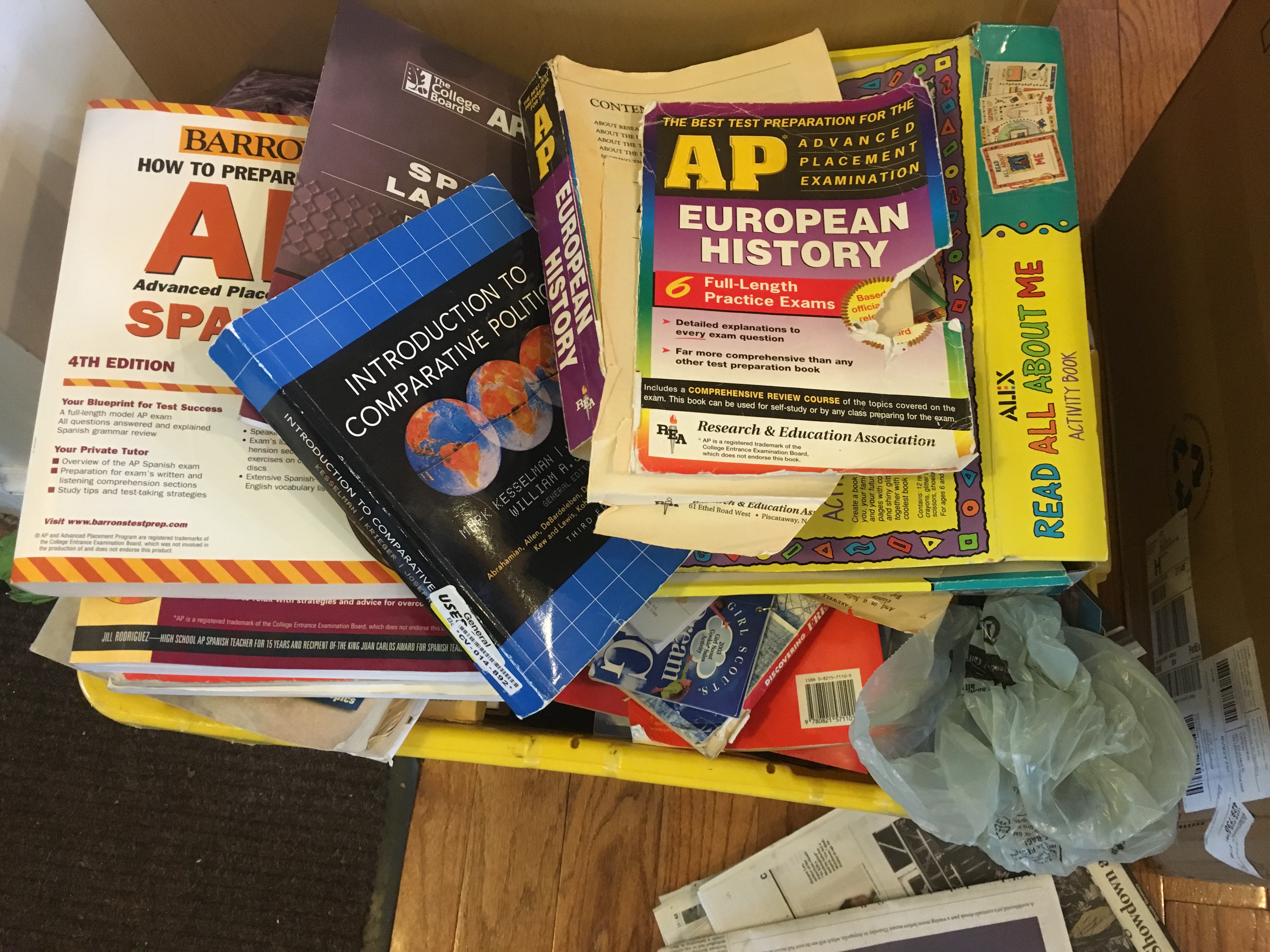

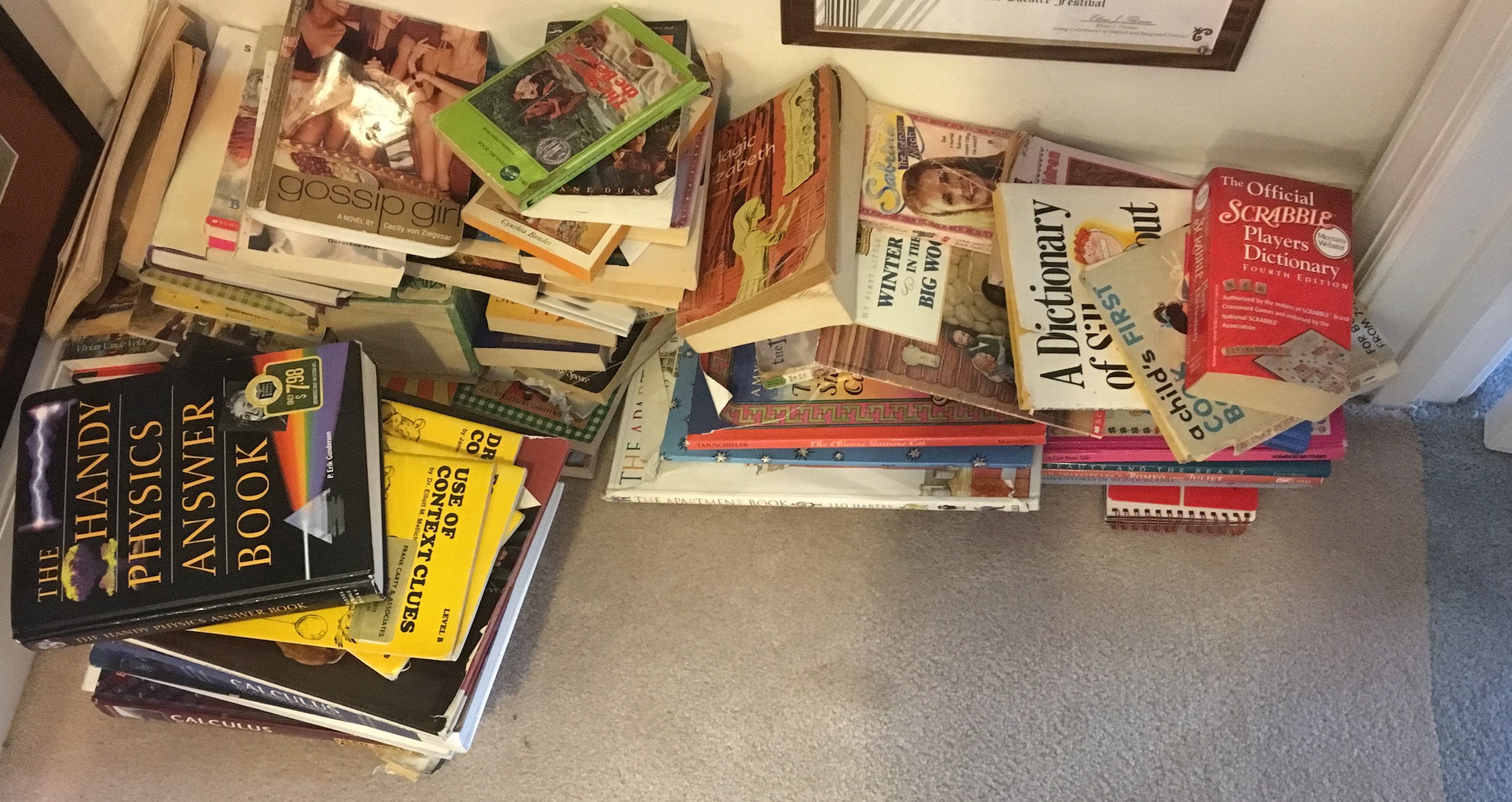

Of course, it’s easier to get rid of someone else’s books than your own—at least for certain books. I had no problem relegating a half-finished crossword puzzle book to the recycling bin, or accepting that a copy of The Fountainhead with half the pages missing or a 10-year-old SAT prep book and torn paperback easy reader could go. Getting rid of Gossip Girl and Sabrina the Teenage Witch books wasn’t too hard either. Even most science books were easily tossed. They were simply out-of-date.

Learning to Let Books Go

Handling things like hardcover picture books or quality young adult fiction was more challenging. These were books we had enjoyed but that had never resonated strongly or that seemed impossible removed from anyone growing up today. Keeping them would amount to kicking the can to my grown children, who I suspected would end up giving them away rather than sharing them with their own children. I had to consider: if my daughter herself didn’t want to save books like Jean Craighead George’s My Side of the Mountain or Patricia C. Wrede’s Shadow of Lyra, books she had adored, wouldn’t they be better off given to someone else to enjoy than stuffed in a box in my basement?

The hardest decisions involved young adult books from my own childhood that I had saved for my own children. Harriet the Spy, The Long Secret, The Little House on the Prairie. Norma Kassirer’s Magic Elizabeth, Palmer Cox’s The Brownies: Their Book, and Elizabeth Enright’s Then There Were Five. Just typing the titles makes me cringe. I distinctly remember choosing some of these books from Scholastic flyers I got at school, or being presented with them by my father. Some of these books weren’t even very good or meaningful to me, but they had been on my shelf or in my home since the age of 8 or 10. How could I let them go now?

I had saved these books for years in the hope that they would bring the same joy to my children they had brought to me, or, in the case of less gripping books, simply because they seemed essential parts of childhood. Now my children had indeed taken what they would from them—read them, or not read them, as they so chose. Now that chapter of my life was over.

Depressing But Liberating

I realized with a jolt that I was at last ready to let these go. Suddenly the idea of saving them for yet another generation seemed silly. Most of these were so dated, or so dog-eared, or so trivial, that I couldn’t imagine another generation having much interest in them. Like any product of the past, they had a certain value, but not enough to be of deep historical interest or to serve as emblematic symbols of their time.

Such thoughts made me realize that I was also probably now ready get rid of the box of Barbie dolls and trolls and china figurines I had saved from my childhood. The lifelong need to pass these things on to another generation was trumped by my realization that I had already done as much as I could do. My granchildren and their children would be too distant from my childhood, and from me, to find most of these objects desirable. If these books and other memorabilia meant something to me, but not to the children I had already saved them for and shared them with, then they were not worth saving.

That was depressing, I admit, but also liberating. Of course, there are some things, and books, that are worth saving. And some material objects that deserve passage from one generation to the next. I still plan to keep items—books or otherwise—that mean so much to me or a member of my family that the thought of no longer possessing them fills me with pain. I will also keep items so rare or irreplaceable that it would be easy to imagine someone in my own family regretting their loss. What was jarring to me was realizing how fewer and fewer items met these standards.

A Triage System

Ultimately I came up with this triage system.

- Recycle unreadable, horribly dated, or seriously damaged books.

- Donate good children’s books that were in tolerable condition but were not treasured memories.

- Gift the very special children’s books that were still in decent shape (generally hardcovers), either by setting aside for my 4-month-old grandson or for some future grandchild.

- Box books that my daughter wanted to save and needed packed up and stored in my basement until she has a more permanent home.

- Reshelve a few treasured books—generally antiques, classics, books with inscriptions from friends and relatives—with remaining household books.

Of course, I can’t let my head get too swollen about this apparent triumph over hoarding. These were not for the most part my books. I still have several truckloads of the latter all over the house. And I assure you, those truckloads are not going anywhere soon. In fact, thanks to my mother-in-law uncluttering her own shelves recently, I’ve just added quite a few hefty new volumes to the collection. Easy go, easy come, I suppose.

Terra Ziporyn

TERRA ZIPORYN is an award-winning novelist, playwright, and science writer whose numerous popular health and medical publications include The New Harvard Guide to Women’s Health, Nameless Diseases, and Alternative Medicine for Dummies. Her novels include Do Not Go Gentle, The Bliss of Solitude, and Time’s Fool, which in 2008 was awarded first prize for historical fiction by the Maryland Writers Association. Terra has participated in both the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and the Old Chatham Writers Conference and for many years was a member of Theatre Building Chicago’s Writers Workshop (New Tuners). A former associate editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), she has a PhD in the history of science and medicine from the University of Chicago and a BA in both history and biology from Yale University, where she also studied playwriting with Ted Tally. Her latest novel, Permanent Makeup, is available in paperback and as a Kindle Select Book.

- Web |

- More Posts(106)