INVISIBLE MEN AND INVISIBLE BOOKS

Several years ago I combed my bookshelves and gave my teenage son some old paperbacks I thought he’d enjoy. Recently, while hunting for a book he asked me to send to him in college, I found the books neatly stacked next to his bed. I wondered if he had ever read any of them.

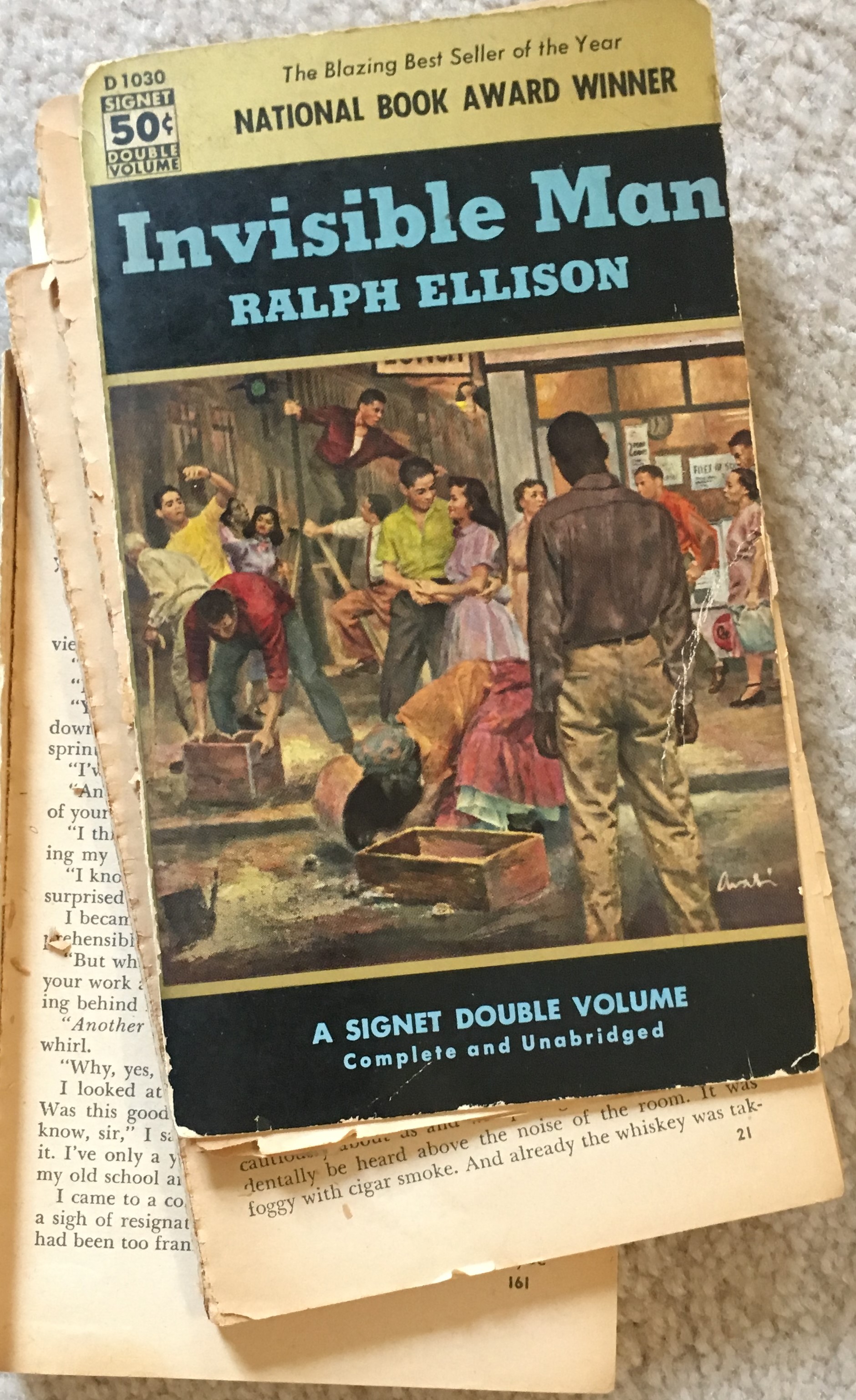

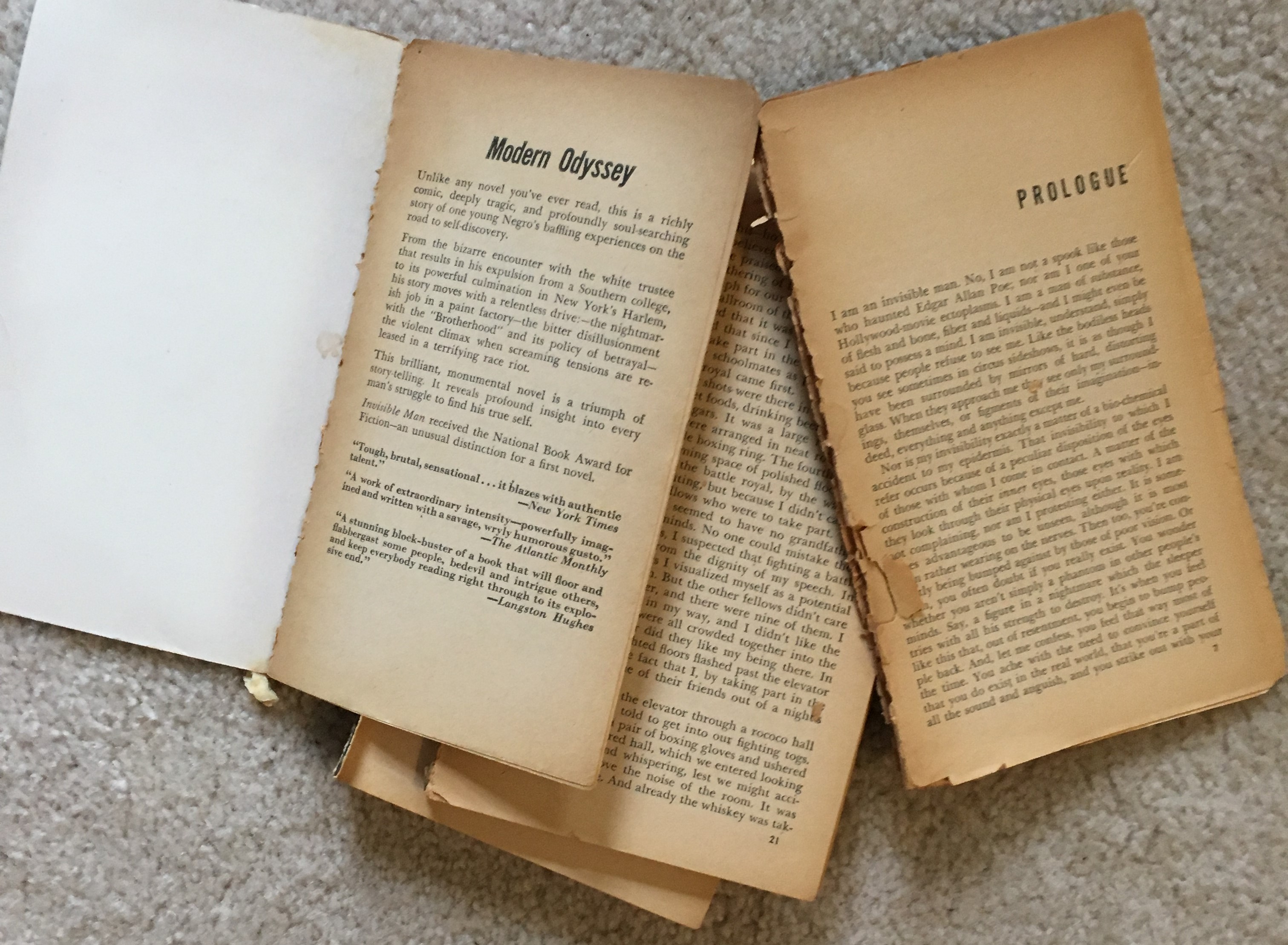

One he had probably not cracked open—or so I thought I had evidence to prove—was Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. I figured this because when I myself opened the book, the pages started shedding.

I had always assumed I had read Invisible Man. Hasn’t everyone? But over the years I realized that somewhere along the line I must have confused my invisible men, mixing up H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man with Ellison’s (“the“-less) Invisible Man. I had read at least one of them, but which?

As with many things, I could no longer distinguish what I had read from what I had merely heard about.

Opening the book made one thing clear: no one had read this particular book in decades. It had belonged to my father, and I had rescued it from my parents’ bookshelf after he died. A 50-cent Penguin Paperback published 1952, the book was in terrible shape. It was one of those cheap paperbacks never meant to stand the test of time.

A Must-Read

The pages were orange and brittle and fell out when I turned them. They smelled faintly of mildew, but also of my parents’ old apartment in Chicago. With every page turn, I half gagged, but also felt my father was back with me.

And yet I had to read it. I had no idea that Ralph Ellison, in addition to being a prize-winning novelist, was a jazz musician. I was hooked as soon as I read a page or two of the prologue. It describes a marijuana-induced vision in which the narrator is able to “see” Louis Armstrong’s music. The parallels between jazz, being black in America, and vision, are brilliant.

“Invisibility,” Ellison writes, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps around.”

And so he is, throughout the novel. I was particularly intrigued because I’ve been on a James Baldwin rage of late. The opening sentences made it abundantly clear that the world the narrator faced in mid-twentieth-century America eerily and depressingly paralleled the one in the headlines today, as eruptions in places like Ferguson, MO or Charlottesville, VA remind us.

This book still needed to be read. Desperately. In fact, my awareness that the book was written over half a century ago made the need to read it even more pressing.

Saved by the Library

Yet I could not read this book. It literally fell apart in my hands once I got beyond the prologue. I tried to battle the pages with scotch tape, but quickly surrendered. The only way I was going to finish it was to get a copy at the public library, and so I did.

I was able to pick up just where I left off. The library book had a different picture on the cover, and a much newer, sturdier binding. It was less compact, and the typeface bigger. Still, the words, and the story, were the same.

Physical books are not meant to last. The words within them are. The story they carry is intangible, and transmutable. This realization was comforting, even an epiphany, to me, a self-confessed book-hoarder. I could no longer justify my idol-worship of physical books. Nor could I justify keeping my father’s leaf-shedding version. I vowed to recycle it, guilt-free.

The Power of Invisible Men

Then a strange thing happened. I couldn’t find the library book. With only the epilogue left to read, I panicked. I searched my nightstand, bed, desk, and kitchen counter. I checked my back deck, where I sometimes read in the morning. I checked the car, even my backpack. It was nowhere I remembered reading or carrying it.

In desperation, I returned to the bedraggled 1952 paperback. I sat on my floor and carefully turned one loose page after another until I had finished the work. My father was with me, and I knew he was happy.

Eventually I found the library book on the living room couch and returned it to the library. My father’s old book, loose pages stacked neatly together, remains in my house. I may look at it, inhale it, a few more times. But then I know I will be able to let the pages go because the story Ellison told, just like my father, is still inside me.

Terra Ziporyn

TERRA ZIPORYN is an award-winning novelist, playwright, and science writer whose numerous popular health and medical publications include The New Harvard Guide to Women’s Health, Nameless Diseases, and Alternative Medicine for Dummies. Her novels include Do Not Go Gentle, The Bliss of Solitude, and Time’s Fool, which in 2008 was awarded first prize for historical fiction by the Maryland Writers Association. Terra has participated in both the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and the Old Chatham Writers Conference and for many years was a member of Theatre Building Chicago’s Writers Workshop (New Tuners). A former associate editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), she has a PhD in the history of science and medicine from the University of Chicago and a BA in both history and biology from Yale University, where she also studied playwriting with Ted Tally. Her latest novel, Permanent Makeup, is available in paperback and as a Kindle Select Book.

- Web |

- More Posts(106)