WALKING AWAY FROM A LITTLE LIFE

I am on page 608 of a book I hate. And the more I read it, the more I hate it. And yet I keep reading.

I am on page 608 of a book I hate. And the more I read it, the more I hate it. And yet I keep reading.

This has to stop.

Why Not Walk Away?

Hate is a strong word. And for the first 300 or so pages of this book, I wouldn’t have used it. I might have even said that I liked the book, or was intrigued by it. But with each passing page, the word “hate” keeps rising to the surface.

I can no longer keep the hate down.

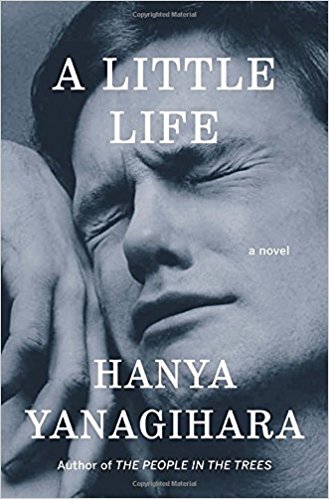

Why don’t I just walk away? Part of it is the book itself, which, by all rights, I should be loving. The book at issue is A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. On the surface it is the story of four college classmates from a prestigious East Coast college who move to New York City and build their lives. Three of the four are artists of some sort: an actor, an architect, and a visual artist. The fourth, Jude, is a lawyer and mathematician with a mysterious past. As the novel progresses we learn that Jude was raised by monks who rescued him from a dumpster only to set him on the road to unfathomable abuse.

My mother, who usually shares my taste in fiction, raved about this novel. She must have told me three times that I had to read it. Finally I succumbed.

And it wasn’t just my mother. The book, all 720 pages of it, won the Kirkus Prize and was a finalist for both the Man Booker Prize and the National Book Award.

A Little Less Life (Please?)

A Little Life has been called “one of the best books of the year” by the likes of The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, People, NPR, The Economist, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, Vanity Fair, Newsday, even Buzzfeed. The New Yorker praised the novel’s “subversive brilliance.” The Guardian said everyone should read this “modern-day classic,” a “refreshingly modern take on friendship in the age of anxiety.”

Who am I to hate such a book? Not only is the thing a blockbuster, but it is the story of elite college graduates making their way in the world. I am usually a sucker for those kinds of books.

Except these friends are sickeningly successful and stupefyingly afflicted. After stints as impoverished artists and idealist young lawyers. they almost meteorically become subjects of Whitney retrospectives, stars of major motion pictures, globetrotting partners at white-shoe law firms, and so forth. All their friends and aquaintances have equally stellar careers or at worse are one degree away from them. Meanwhile, these superstars experience afflictions as stunning as their success is stellar.

Just like some critics, I feel scammed. And the more I read, the more scammed I feel.

Virtually every character can claim achievements so sickeningly and consistently extraordinary, and tragedies so unthinkable, that you almost have to laugh. Every time you think you have reached the climax, and uncovered the horror underlying all the other horrors, it turns out to be just another of a tsunami of unthinkable abuses.

After the first two of three horror stories, I began to wish that A Little Life had a little less life. The depth of the suffering, combined with the absurdity of achievement, eventually leaves you numb. There are so many atrocities, I stopped caring. I just wanted it to be over.

Feeling Manipulated

A LIttle Life has been praised for its exquisite writing, but here, too, I beg to disagree. Most characters other than Jude are undeveloped, seemingly thrown in as foils. And for all the moving images and vignettes, other statements and scenarios seem gratuitous, even sloppy. Statements about a character’s feelings or actions are sometimes directly contradicted two pages later.

Details are sometimes sloppy and suspicious, to the point that you feel manipulated. Among these are various unnamed, sometimes unbelievable, diseases that Jude suffers. And then there is character history that shows up hundreds of pages into the book only to introduce a new and meandering plot point.

And speaking of plot: Once we discover the climactic atrocity explaining Jude’s greatest disability, the plot fizzles. With hundreds of pages to go, the only story left to tell, other than Jude’s inevitable descent, is the passage of time (with plenty of gratuitious atrocities thrown in, of course, including a couple of horrific deaths).

I am glad to know I’m not alone here in my negativity. Despite the accolades this book has had its share of criticism.

One of the critics who calls out the book is, Daniel Mendelsohn. In The New York Review of Books, he labels A Little Life a “striptease among pals,” with the Jude’s secrets sequentially uncovered until we reach the “pivotal moment of abuse”—although, really, his entire life is nothing short of a torture chamber. You do have to wonder, if everyone is praising the book not so much for itself but because it addresses subjects we’re all supposed to care about right now.

The one thing this book does get right is its title. It is indeed “a little life,” or, rather a short one. And it’s too short to waste time on bad books.

The Subjectivity of Success

So, again: why not walk away? Why must I finish a book I despise? My only answer is that I have a bad habit, a compulsion to finish whatever I start. I can no longer deny it. I am one of those people who will not walk out of a bad movie—or a bad book.

Also hard for me is writing such a mean-spirited thing about someone else’s work. But it is only my personal opinion. Others clearly disagree, so I doubt it matters much. Still, being able to say it is an important reminder for me, and for all writers. As much as I agonize over the limitations of my own books, saying it is a reminder that ultimately the worth of a book is subjective.

I sometimes feel like a failure because I have not, and probably never will, be the author of “one of the best books of [fill in the year].” I will not win the Man Booker Prize, or even be short-listed for it. I will not see a play of mine on Broadway. But somehow it makes me feel better to know that, even if I did, someone—and not just frustrated writers—will think that I didn’t deserve those accolades anyway.

Acclaimed authors do all the things that supposedly ruin the works by unacclaimed authors. Clearly there is much more to acclaim than writers programs would have you believe.

There is comfort here, and empowerment. Even liberation in a way. Acclaim may come, or go, or never come at all. So we need to write what meets our own standards. We need to set and then aim at our own goals. The same is true for our choice of reading material. Man Booker prizes or not, we need to to call out unclothed Emperors when we see them.

As for A Little Life, I will finish the book since I have just over 100 pages to go. I’m afraid it will be pure torture, but I’m too far gone not to finish it.

Remind me next time, however, to trust my own judgment and walk away.

Terra Ziporyn

TERRA ZIPORYN is an award-winning novelist, playwright, and science writer whose numerous popular health and medical publications include The New Harvard Guide to Women’s Health, Nameless Diseases, and Alternative Medicine for Dummies. Her novels include Do Not Go Gentle, The Bliss of Solitude, and Time’s Fool, which in 2008 was awarded first prize for historical fiction by the Maryland Writers Association. Terra has participated in both the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and the Old Chatham Writers Conference and for many years was a member of Theatre Building Chicago’s Writers Workshop (New Tuners). A former associate editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), she has a PhD in the history of science and medicine from the University of Chicago and a BA in both history and biology from Yale University, where she also studied playwriting with Ted Tally. Her latest novel, Permanent Makeup, is available in paperback and as a Kindle Select Book.

- Web |

- More Posts(106)