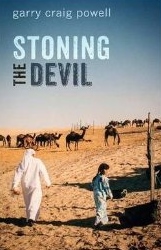

Stoning the Devil, Garry Craig Powell, book review and interview

2/20/14 STONING THE DEVIL, GARRY CRAIG POWELL, BOOK REVIEW AND INTERVIEW

2/20/14 STONING THE DEVIL, GARRY CRAIG POWELL, BOOK REVIEW AND INTERVIEW

Time and fortune happen to everyone. Before my other half, Todd, read Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning the Devil, I told Todd that when he finished I would want him to tell me if he could see any difference between Stoning the Devil and the novels on the New York Times notable books lists over the years. Because I can’t see any difference, in quality of writing or in the relevance and significance of topic.

Todd couldn’t see any difference, either.

Paula Mendoza wrote a great review of Stoning on lipstickandpolitics.com. Here’s the review’s first paragraph, which I feel sums up Stoning the Devil better than I could:

“Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning the Devil interweaves narratives of sex, power and identity through a feminist lens, with all of the contradictions and myriad facets that perspective affords. This episodic novel—each chapter of which is complete unto itself—is first and foremost a work of lush and vivid prose. Various formal innovations, from the epistolary opening chapter to the syntactic feat of the chapter entitled “Sentence,” demonstrate Powell’s technical virtuosity. It’s this skill that allows him to capture the Gulf landscape’s severe beauty, alongside a wealthy city’s urban sheen and excess, with clarity that feels neither detached nor heavy-handed. While the Gulf in general, and the UAE in particular, almost function as their own characters in the book, it’s those souls who suffer and thrive in the foreground whom Powell trains his, and in turn the readers’, attention on. The characters which inhabit Stoning’s pages are sensitively drawn and attuned readers will find themselves quickly invested in the lives of Badria, Fayruz, Alia and all the other “players” of this novel.”

Born in England and educated in Cambridge University and Durham University, Garry Craig Powell is a professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas. He also has lived in Spain, Poland, Portugal, and the United Arab Emirates and has played rock guitar semi-professionally.

Born in England and educated in Cambridge University and Durham University, Garry Craig Powell is a professor of Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas. He also has lived in Spain, Poland, Portugal, and the United Arab Emirates and has played rock guitar semi-professionally.

For today’s discussion, I have four questions for Powell:

Q: Stoning the Devil is about women in a society where they’re told that respectable women—mens’ girlfriends, wives, mothers, sisters—should never, outside the marital bedroom, show any evidence that they are capable of sexual feeling or thought. I am gay and came of age when homosexuality was still criminalized in the U.S., so as a reader it was easy for me to be right there with these Middle Eastern women in their anguished struggle over what to do with a sexual nature they are told they can’t legally have. Reading the book, I marveled at how a heterosexual male author could so effectively get under the skin of his female characters living with repression. How did you do it?

A: I have been asked this a lot. Partly, I think, I was lucky: I had the opportunity to work at the women’s campus of the national university in the UAE for five years, so I was in constant contact with young Arab women, who were surprisingly keen to tell me their stories. Because I took risks, opening up to them about my own private life when we were in one-on-one situations, they often reciprocated, and a number of the key events in the book have their roots in stories told me by students (always changed, of course, to protect the identities of the people involved). But I think any good writer has to be somewhat androgynous. It’s part of the writer’s job to be able to imagine himself or herself inside the mind of someone quite different. Shakespeare and Tolstoy both do it very well; so do Flaubert and Chekhov. I think it helps if you love women and find them fascinating, which I do. When you consider how hard women’s lives are, even here in the West, and what terrible strictures and suffering they have to undergo because of men, that inevitably becomes a theme in your work. You know George Cukor was considered a “woman’s director” in Hollywood. I like to think of myself as the sort of George Cukor of fiction. Perhaps that’s vain of me, but I have been told again and again by women that I get their psychology right. And my highest accolades have come from feminist critics.

Q: I read Stoning as a book about men in the UAE circumscribing female sexuality and in so doing unwittingly limiting or defeating their own potential as sexual and social partners. If you were to write a Stoning the Devil set in the U.S. or in Europe, what male-female conflicts would plague your characters? To your novelist’s eye, do Western women in significant number, or in identifiable exceptions, succumb to men defining them in a way that’s counterproductive for both men and women? Is the kind of dysfunction between men and women you portray in the novel culturally specific to the Arab World?

A: Let me answer those in reverse order. No, obviously the kind of dysfunction I portray in Stoning the Devil is by no means limited to the Arab World. The world is still run on pretty patriarchal lines. India, Japan and Korea, much of Africa and Latin America show this very clearly. In the West it’s a little different, because there, especially in North America and northern Europe, equality for women is the official creed, and is legally protected, but of course that doesn’t mean that all the problems are solved. Men are still defining women in these countries, but in new and perhaps even more pernicious ways. In the West, the ideal of the woman is no longer the “pure” virgin or mother, but a hyper-sexualized love-goddess with a perfect body. Since women are now liberated sexually, they are expected to cater to men’s pleasure at all times. Never in history have women’s fashions been so overtly provocative. A lot of feminists defend a woman’s right to own her sexuality and present herself as a sexual being, which I understand, but there’s a great deal of pressure to look a certain way and behave a certain way, and very little reward for it. Women are treated by many men as disposable toys. (Of course the converse is also true.) The other thing that’s happened in the West is that feminism has taught women they must be assertive, and I think that’s often taken to absurd lengths. This is not so much a matter of women’s roles being defined by men as by other women. What it amounts to is that in order to succeed in a man’s world, a woman has to behave like a man—aggressively, basically. Joni Mitchell has spoken of the “grotesque aggressiveness” of American women, and the corresponding weakness of American men, and she’s hardly an apologist for traditional values. These are in fact the issues that Martin Amis writes about, to some people’s minds from a misogynistic perspective, but I think at the least he understands the issues we’re facing. For the first time in history in a developed society, women have control over their reproductive rights, and if not full economic equality, at least the means to financial independence, so in theory they are not subject to control by men. But as yet, we have not come to a modus vivendi. The rules of engagement are still being negotiated. It’s very difficult for women, who often struggle to be both perfect traditional role models, wives and mothers, and at the same time liberated modern ones, career women who are sexually free. But it’s also hard for men. In the past a man knew where he stood and how he was supposed to behave. Nowadays men are confused. On the one hand they’re told that women want them to be sensitive, to help with the housework, child-rearing and so on; on the other, the images of men promoted in the media are still of muscle-bound action heroes. A glance at Hollywood’s favorite actors shows this. So most people are doing a kind of dance between traditional roles and so-called liberated ones, and it’s exhausting and perplexing. I’m afraid I’ve answered this more as a journalist might than a fiction writer. If I were to write something like Stoning the Devil set in the US or England, I would probably try to show these tensions. It strikes me that love between a man and a woman is rare, because they so often see one another as antagonists. That’s a great pity. I still believe in the Provencal ideal of romantic love, but for that to work you have to see yourself as part of a union, not as a person in opposition to another.

Q: What are you writing now?

A: It’s another novel set in a different society: Italy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The main character is Gabriele D’ Annunzio, who was the most important writer in his country at that time, as well as the most celebrated playboy, the most decorated soldier, and without question the most influential statesman, at least up to Mussolini. He was a predatory lover, incredibly successful with women despite his short stature, lack of good looks, and rather androgynous nature—he had a narrow chest, wide hips, and feminine gestures—and had sado-masochistic inclinations. He subscribed to the most elemental view of men as conquerors and his views were extremely influential. So in a way I’m looking at the same questions of gender relations and sexual identity from a different angle. D’ Annunzio might seem a peculiarly repulsive character, but in fact there was a complexity about him that fascinates. He was a superb poet, could be extremely sensitive, and was a champion of cunnilingus, which at the time was considered humiliating and effeminate for a man. And how did this ugly little guy seduce the most accomplished women of his time? That’s interesting, is it not? And how could a man who joined the armed forces at the age of fifty-two become the most decorated warrior of his country? How could he end up founding a short-lived pirate kingdom on the Adriatic that had world leaders like Woodrow Wilson trembling with fear? He believed he was a super-man, the Nietzschean ubermensch, and his central idea, that you can, through sheer will, make anything of yourself that you like, is a theme that the novel explores. It’s a very ambitious work. If I can pull it off, it may well be my masterpiece. If not, it might destroy me.

Q: Do you still play the guitar?

Q: Do you still play the guitar?

A: Yes, of course. That’s something I will always do, as long as I don’t get arthritis in my hands. This month my band, Slings and Arrows, are playing two benefit shows for charities and a commercial gig at a downtown bar. Last year we released an album of originals, half of them composed by me, “Outrageous Fortune”, which is available on iTunes. Compared with the writing, it’s a hobby. But singing with a good Southern roots band—that’s a real pleasure.

Gary Garth McCann

First-prize winner for short works and for suspense/mystery, Maryland Writers’ Association, Gary Garth McCann is the author of the novella Young and in Love? and of the novels The Shape of the Earth and The Man Who Asked To Be Killed, praised at the Washington Independent Review of Books. His most recent published stories are available online in Chelsea Station Magazine, Erotic Review Magazine, and in Mobius: The Journal of Social Change. His other stories appear in The Q Review, reprinted in Off the Rocks, in Best Gay Love Stories 2005, and in the Harrington Gay Men’s Fiction Quarterly. See his blogs at garygarthmccann.com and streamlinermemories.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(57)