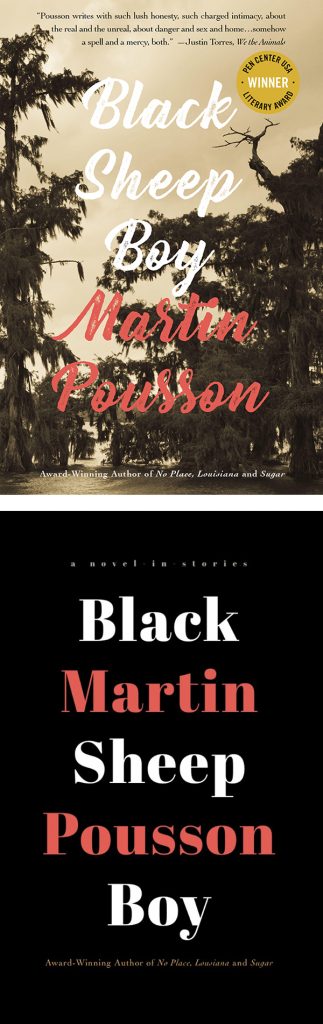

INTERVIEW WITH MARTIN POUSSON ABOUT HIS 2017 PEN CENTER AWARD-WINNING NOVEL BLACK SHEEP BOY

“If you don’t push against the mirror, how do you know you’re standing in front of it?” asks author Martin Pousson. His PEN award-winning novel Black Sheep Boy, also an L.A. TimesPick of the Week, inspired Susan Larson (NPR The Reading Life) to say: “An unforgettable novel-in-stories about growing up gay in French Acadiana, so vivid and almost fairy tale-like, drawing on folklore from the region, and yet so brutally realistic. Brilliant. I loved this book.” I loved it too, for Pousson’s poetic prose, among other reasons. I’ve been able to ask Martin Pousson a few questions about the novel. His answers reflect his literary acuity.

“If you don’t push against the mirror, how do you know you’re standing in front of it?” asks author Martin Pousson. His PEN award-winning novel Black Sheep Boy, also an L.A. TimesPick of the Week, inspired Susan Larson (NPR The Reading Life) to say: “An unforgettable novel-in-stories about growing up gay in French Acadiana, so vivid and almost fairy tale-like, drawing on folklore from the region, and yet so brutally realistic. Brilliant. I loved this book.” I loved it too, for Pousson’s poetic prose, among other reasons. I’ve been able to ask Martin Pousson a few questions about the novel. His answers reflect his literary acuity.

Question: I either read or heard said that Edward Albee couldn’t write Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in today’s world in which gay writers are expected to be out and expected to write gay characters. Does this seem so to you? Can you imagine yourself writing a novel in which the protagonist is, say, the mother in Black Sheep Boy and the story is of her without a son? Or perhaps writing a novel in which one of the protagonist’s cousins in Black Sheep Boy is the protagonist in a struggle to find love with a woman and to eek out a living in backcountry Louisiana?

Question: I either read or heard said that Edward Albee couldn’t write Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in today’s world in which gay writers are expected to be out and expected to write gay characters. Does this seem so to you? Can you imagine yourself writing a novel in which the protagonist is, say, the mother in Black Sheep Boy and the story is of her without a son? Or perhaps writing a novel in which one of the protagonist’s cousins in Black Sheep Boy is the protagonist in a struggle to find love with a woman and to eek out a living in backcountry Louisiana?

Answer: Yes, I wrote that novel already! My first novel, No Place, Louisiana, is the story of a straight man and a straight woman and a marriage gone wrong as a culture collapses and as an American dream vanishes. Like Black Sheep Boy, the novel is set in Acadiana, in the bayou land of Louisiana, but it features a wholly different set of characters and is written in a wholly different genre. It’s a realist novel with Southern Gothic themes. It chiefly centers on the two-step marital waltz of Nita & Louis Toussaint, with one plot but two frames, as if they were competing witnesses in a crime that runs across lines of class, religion, race, ethnicity, and gender. The dead body is the (Acadian) past, and the killer is the (American) present.

Question: I recall the noted gay author Edmund White writing a gay protagonist who was attracted and repulsed by his father. My memory is that the boy stands at the bathroom doorway to watch his father piss, something I remember doing as a kid. The father in White didn’t know what to do with his gay son (nor probably did mine, not that either of us, back in those dark ages, put words to what I was). Your narrator in Black Sheep Boy has awkward experiences with his father likely familiar to many gay male readers. When a boy attracted to his father is horny, he’ll do anything to be near Dad; when the boy isn’t horny (in other words, for a short while after he’s masturbated) he distains manliness. If fathers might expect daughters to have a crush on them—if society smiles at this—fathers don’t expect sons to be attracted to them and don’t know what to do with sons who are. The father in Black Sheep Boy avoids his son altogether. What might you say to a reader whose gay son is attracted to him?

Answer: While I’m familiar with the trope you describe in gay male fiction, that’s not the experience of Boo, the narrator of Black Sheep Boy. If there’s a body he wants to possess, it’s not his father’s but his mother’s. Yet for him, the idea of possession is not sexual, not at all. Rather, he wants to possess his mother’s body only so that he may inhabit it, may know what it’s like to be the center of attention in a room full of men or in the middle of Mardi Gras. He wants her face, her features, maybe even her dress and gestures, because he sees the power in being a Southern woman, especially a Southern Louisiana woman. If his father has anything he wants to possess, it’s not his body but his song and his memory. When Boo sees his father urinating in the bathroom, he’s not excited by his father’s flesh but by his fantasy. His father sings a dirty Creole song out of sight of his moralizing mother. The song, “Danse Colinda,” offers Boo temporary relief from his own boxed-in identity. He’s pushed by his mother to look “pure French” (or white), to worship Catholic (not voodoo), to “act straight” (not queer), yet the song is a Haitian-French-Indian mixed-up dance performed by shirtless men doing battle with each other against tradition and convention to assert their sexuality. That’s what excites Boo.

Answer: While I’m familiar with the trope you describe in gay male fiction, that’s not the experience of Boo, the narrator of Black Sheep Boy. If there’s a body he wants to possess, it’s not his father’s but his mother’s. Yet for him, the idea of possession is not sexual, not at all. Rather, he wants to possess his mother’s body only so that he may inhabit it, may know what it’s like to be the center of attention in a room full of men or in the middle of Mardi Gras. He wants her face, her features, maybe even her dress and gestures, because he sees the power in being a Southern woman, especially a Southern Louisiana woman. If his father has anything he wants to possess, it’s not his body but his song and his memory. When Boo sees his father urinating in the bathroom, he’s not excited by his father’s flesh but by his fantasy. His father sings a dirty Creole song out of sight of his moralizing mother. The song, “Danse Colinda,” offers Boo temporary relief from his own boxed-in identity. He’s pushed by his mother to look “pure French” (or white), to worship Catholic (not voodoo), to “act straight” (not queer), yet the song is a Haitian-French-Indian mixed-up dance performed by shirtless men doing battle with each other against tradition and convention to assert their sexuality. That’s what excites Boo.

Question: The mother’s domination of the marriage is another reason the narrator’s father essentially disappears from his son’s life in Black Sheep Boy. When I think of my own upbringing, I realize that my mother certainly dominated home life, while my father worked overtime as a grocery clerk. Aren’t most American wives the dominant force in their marriages? Does this affect a gay child differently than a straight child? Might the feminist movement—with its push for equal division of home-life responsibilities—change how children experience their parents?

Answer: The answer to your question may be geographical. Sometimes, I doubt there’s any such monolith as “America.” In far too many places where I’ve lived in this nation (outside of Acadiana), women are not at all a dominant force, in their marriages, in their careers, in their fortunes. Women are still underpaid and undervalued in most of the USA, subjected to domestic abuse, workplace harassment, and financial dependence. Most women still make less, a third less, than men who work the exact same job. Most women still take the surname of their husband upon marriage, which is not only literarily symbolic but also legally significant. Even in Acadiana, Nita’s mother tells her (when she drops out of school at 16 to marry Louis) that for a woman “marriage is the real diploma.” Nita’s ultimate triumph is also the triumph of Boo’s mother in Black Sheep Boy: she topples the power structure. She throws off old roles. True, she pushes Boo toward convention and conformity, yet she creates a whole new role for a woman in the home—and out of the home. In the end, Boo is not emasculated by his mother, far from it. If anything, when it comes to gender, he is encouraged by her bold defiance of the social order. She may not like the step he takes into his queerness, but it’s a step he couldn’t have imagined without witnessing the fire of her own power.

Question: By adolescence, the protagonist of Black Sheep Boy becomes heavily involved in drugs, drag, and disco. I think this part of the book is more about counterculture—for my generation, it could be the hippie movement of the ’sixties—than about gay lifestyle. Are you interested in countercultures other than within the gay world? If you wrote a gay protagonist at a typical university, do you think being gay would make him automatically a part of a counterculture?

Answer: When I grew up, to be “gay” was countercultural, since gay relationships were all but illegitimated. For example, “gay marriage” was illegal. Now, though, with marriage equality and other progress toward inclusivity, there’s little “counter” about gay identity. Boo is not gay; he’s queer. While he’d admit to a gay identity in that he sleeps with men, only men, he’s queer not just in bed but outside of it. He rejects convention and conformity. He straddles genders. Those aspects of his identity aren’t a lifestyle. In fact, I’ve never understood that term when applied to identity. Once, the Jesuit President of Loyola University used the term in the school newspaper, something like: “it’s not the gay we condone but the gay lifestyle.” A euphemism for “we love the sinner but not the sin.” Now look at those two sentences side by side. Lifestyle becomes a substitute for sexual behavior. Queerness is not sexual behavior; it’s a social attitude. For Boo, who grows up in the height of the AIDS pandemic, drugs, drag and disco are not just a counterculture but a counter-reality. If you don’t push against the mirror, how do you know you’re standing in front of it? If you don’t test the limits of reality, how do you create fantasy? How do you manifest a dream? The drugs are a vehicle, the drag is a costume, but the disco is a church, and the faith is a dance between the known and the unknown, the real and the unreal, the familiar and the strange. To remake the world, we must first unsettle it. It’s not a party so much as a movement.

Question: Do you have a third novel in progress? Will it also take the form of stories? When might we look for it?

Answer: A Cajun cook never can tell exactly how long to stir the roux, how often to turn the spit, or how much cayenne to add. To follow a recipe is to forsake all feeling. Yet that cook never stops cooking and always cooks with more intuition than intellect. I’m not a smart enough writer to know what I’m writing next, but I know better than to talk before it’s done. I have no idea what I might write, but I know that it’ll be in line with Cajun storytelling tradition. We tell the same story out loud again and again, not to repeat ourselves but to surprise ourselves, for no matter how many times we tell the tale, we still have no idea how it may turn out in the end.

Thank you, Martin Pousson, for joining us in the pages of Late Last Night Books magazine.

~~~

Martin Pousson is a Professor in the College of Humanities, California State University Northridge, where he teaches in the Creative Writing Program and the Queer Studies Program. He was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship for his novel-in-stories, Black Sheep Boy. The stories have appeared in The Antioch Review, Epoch, Five Points, StoryQuarterly, and elsewhere. One of the stories was a finalist in the Glimmer Train Very Short Fiction Award. His first novel, No Place, Louisiana, was a finalist for the John Gardner Fiction Book Award, and his first collection of poetry, Sugar, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award. He also received an Outstanding Faculty Award for Exceptional Creative Accomplishment. As an undergraduate student at Loyola University in New Orleans, he founded Out/Here, the first LGBTQ organization on a southern Jesuit campus, and he was an activist with the NO/AIDS Task Force. As a graduate student at Columbia University in New York, he founded a School of the Arts reading series, and he protested with ACT UP and Queer Nation. As a faculty member at CSUN, he has served as Advisor for LGBTQA, Queer Ambassadors, and Northridge Creative Writing Circle.

Martin Pousson is a Professor in the College of Humanities, California State University Northridge, where he teaches in the Creative Writing Program and the Queer Studies Program. He was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship for his novel-in-stories, Black Sheep Boy. The stories have appeared in The Antioch Review, Epoch, Five Points, StoryQuarterly, and elsewhere. One of the stories was a finalist in the Glimmer Train Very Short Fiction Award. His first novel, No Place, Louisiana, was a finalist for the John Gardner Fiction Book Award, and his first collection of poetry, Sugar, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award. He also received an Outstanding Faculty Award for Exceptional Creative Accomplishment. As an undergraduate student at Loyola University in New Orleans, he founded Out/Here, the first LGBTQ organization on a southern Jesuit campus, and he was an activist with the NO/AIDS Task Force. As a graduate student at Columbia University in New York, he founded a School of the Arts reading series, and he protested with ACT UP and Queer Nation. As a faculty member at CSUN, he has served as Advisor for LGBTQA, Queer Ambassadors, and Northridge Creative Writing Circle.

Gary Garth McCann

First-prize winner for short works and for suspense/mystery, Maryland Writers’ Association, Gary Garth McCann is the author of the novella Young and in Love? and of the novels The Shape of the Earth and The Man Who Asked To Be Killed, praised at the Washington Independent Review of Books. His most recent published stories are available online in Chelsea Station Magazine, Erotic Review Magazine, and in Mobius: The Journal of Social Change. His other stories appear in The Q Review, reprinted in Off the Rocks, in Best Gay Love Stories 2005, and in the Harrington Gay Men’s Fiction Quarterly. See his blogs at garygarthmccann.com and streamlinermemories.com.

- Web |

- More Posts(57)