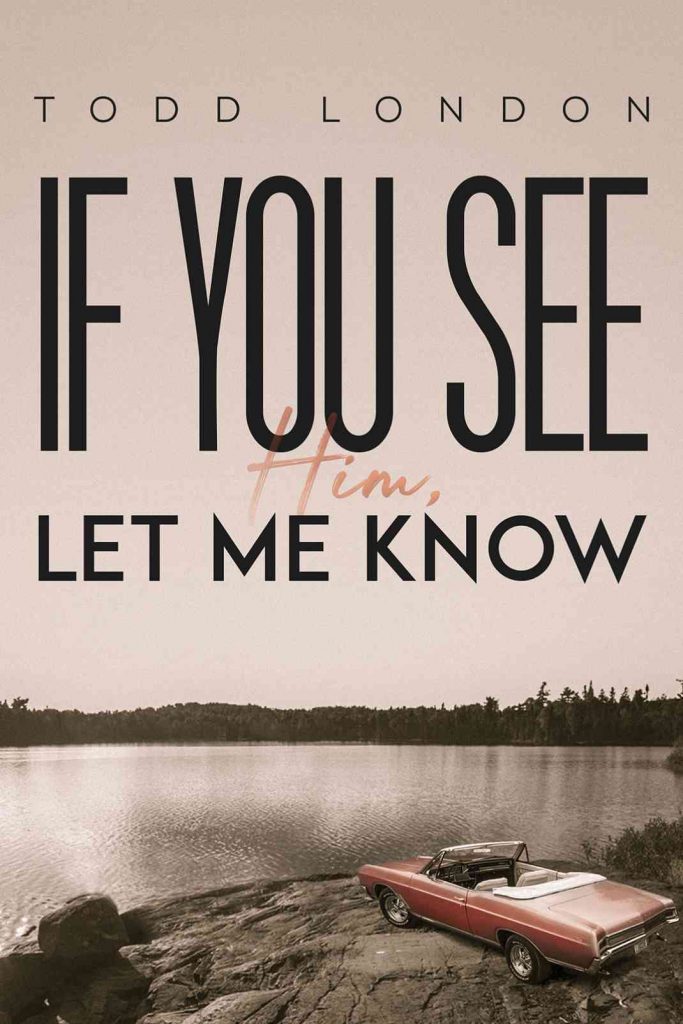

AN INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR TODD LONDON

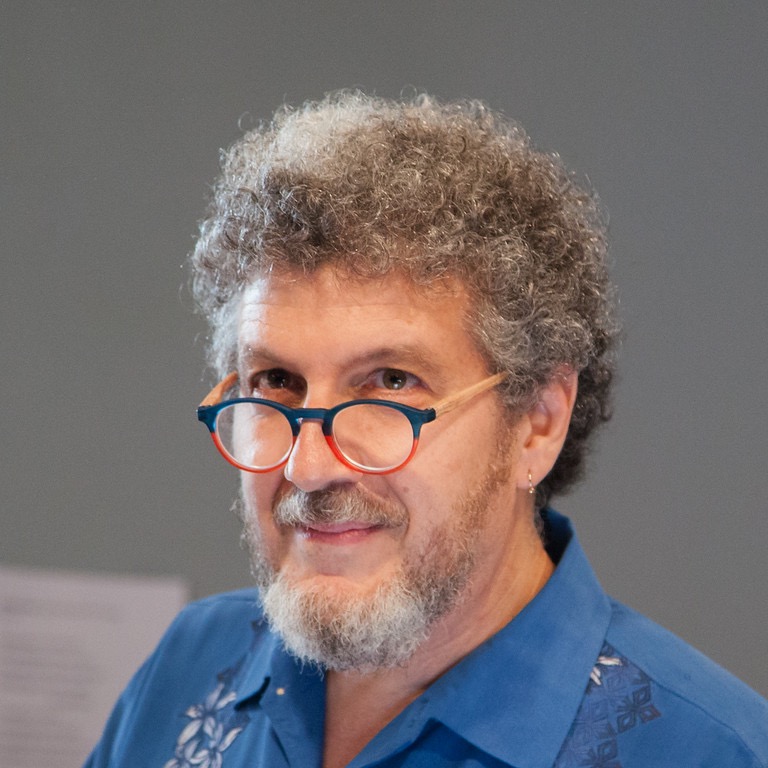

I grew up surrounded by a dazzling number of talented classmates in Evanston, IL. Many went on to become world-famous academics, politicians, actors, directors, screenwriters, playwrights, and novelists. Todd London, the author of the new novel If You See Him, Let Me Know, was one of those people.

Todd lived right down the street from me, and we went to junior high and high school together. We even attended the same summer camp. But neither of us ever realized that last part, partly because I was too shy and insecure (or perhaps too vain and self-absorbed) to connect with him.

Todd is now Head of the MFA Playwriting Program at the New School, School of Drama and the Director of Theatre Relations for the Dramatists Guild of America. He previously served as the Executive Director of the University of Washington’s School of Drama, where he held the Floyd U. Jones Family Endowed Chair in Drama. Before that he spent 18 seasons as Artistic Director of New York’s New Dramatists, the nation’s oldest laboratory theatre for playwrights, where he created programs for and worked closely with more than a hundred and fifty of America’s leading playwrights and advocated nationally and internationally for hundreds more.

I last talked to Todd at a DC signing for his book Outrageous Fortune: The Life and Times of the New American Play, a book of great interest to me as an occasional playwright. But I was even more eager to talk to him about If Your See Him…–which happens to feature our shared summer camp. The camp has particular resonance for me because it was started by two sisters who grew up in Chicago’s Humboldt Park with my late father. I actually still have a decaying copy of Booth Tarkington’s Penrod and Sam that their parents gave and inscribed to my dad on his 9th birthday.

In this interview, Todd was gracious enough to answer my many questions about the new novel and writing more generally.

‘You Can’t Write a Novel on Deadline’

TZ: I know all too well what it’s like to have one particular book project take years, even decades to complete, no matter how productive or prolific you might be more generally. When did you start working on If Your See Him, Let Me Know, and what challenges did you face in finishing it?

TL: There are two answers to the when question: the first is 2002, in the year following the publication of my first novel. That’s when I started writing what became If You See Him…(though it had a different title, the first of many). The second, real answer is that I started writing it around 1981 and again after my father died in 1989.

I was in Boston in ’81, finishing my MFA in directing and trying to write a novel about summer camp. My grief over the death of my father—and my attempts to understand his life—has permeated my writing since then, though I could never find a way to tackle it directly. (By the way, my relationship with my father was not at all like Philip’s with Jerry, though many of the details of Jerry’s life were stolen directly from my father’s.) At some point, though, after I began this particular book in earnest (that’s the 2002 start date), I found out that the way to write each of these novels, the camp one and the dad one, was to write them as one.

Novels tell you what they need, and they take the time (all the time) they take. You can’t force them to fit your idea of a timeline.

The challenges were many—structural, narrative, emotional (challenges of confidence). The biggest challenge was overcoming my own limitations as a storyteller and shaper of this long form thing called a novel. And despair. Lots of life happened during those long years—divorce, remarriage, the birth of a child, a new job, a cross-country move (and back four years later), a couple of agents, and, as you mention, several other books with more pressing deadlines and, in some cases, collaborators I was responsible to. I kept working on the novel, but sometimes working meant putting it away for a while or convincing myself it was worth sticking with, that I could solve it.

TZ: Like your first novel, The World’s Room, published nearly 20 years ago, your new novel has been described as a “coming of age” tale. Do you agree, and, if so, in what ways do the tales differ?

TL: I love to hear how different readers make narrative or categorical sense of the books, but I don’t really think of either as a “coming of age” story. If anything, they share the experience of coming into self by digging out from under family history and inherited trauma. In The World’s Room, the narrator’s older brother, a sweet and probably schizophrenic boy, commits suicide, and the young narrator attempts to replace his brother within the fractured family, even adopting the dead boy’s name as his own, a renaming the family allows to happen. It’s a grief-stricken book about someone who is literally and figuratively writing himself to life.

If You See Him, Let Me Know, while centered on the adolescence of two of the main characters—and their friends—which might make it feel like a coming-of-age tale, also centers two older characters. I intended it as a story of two generations—the adults who came of age during WWII and the late baby boomers, specifically midwestern suburban teens, who lived a more protected and uneventful life (in the sense of historical event) than their parents. I certainly think there’s good reason to read it as the story of Philip’s coming of age, since he’s the person most affected by the other people and their actions.

For me, though, I’ve always thought of it as a “social novel,” my attempt to write a small world into large life, the way (excuse my presumption) the great George Eliot made a world out of provincial life in Middlemarch. I wanted to describe a passage of time in a very precise place, rather than the singular journey of a young man.

TZ: Is there anything you learned about writing and/or publishing the first novel that shaped your approach to the second?

TL: So many things! But the most important: You (or at least I) can’t write a novel on deadline. I’ve worked as an essayist and arts journalist and writer for hire, and I can write on the clock and to a date. Novels tell you what they need, and they take the time (all the time) they take. You can’t force them to fit your idea of a timeline. The other thing I learned is that one novel can’t help me write the next one. You’re on your own each time. Writing blind. The only way the first novel helps the second is that it stands as proof that you can do it, because you have!

TZ: You’re widely recognized as an expert in the field of theatre and playwriting, and you feature theatre in this novel. What made you decide to tell this tale as a novel, not a play?

TL: I work with playwrights and teach playwrights and even married a playwright, but I’ve never in my adult life tried to or wanted to write a play. I love description too much. And narrative voice. Dialogue is fun, but I can’t imagine—for all my life with plays and playwrights—who would want to limit themselves in that way. Also, I love sentences most of all. No work makes me happier than forming—and re-forming—sentences.

You’ll Never Walk Alone

TZ: If You See Him… largely takes place in a fictionalized version of a summer theatre camp run by two actress sisters, who are based on the real-life pair Pearl and Sulie Harand. I recognize many of my own memories in your re-telling. I also recognize many other characters, events, and other details—although I’m not sure whether these memories are accurate or just credible composites of vague impressions (my confusion is a credit to you). How did you decide who and what to fictionalize? And how challenging was it to weave real people and events into a fictional narrative?

TL: I set out to capture the impact of Pearl Harand Gaffin on my life and to understand how my father’s wartime experience might have affected his life choices. It has always seemed to me that they were the two most formative people in my life—as I inherited my father’s history and story, and as Pearl offered a different vision of the world, a set of values that continues to guide me. They—and Pearl’s sister Sulie and their husbands, Sam and Byron, the co-founders of Harand Camp—are the only actual people on whom I based characters in the book, though of course they’re my versions of those people with details added as needed to tell this story.

I work with playwrights and teach playwrights and even married a playwright, but I’ve never in my adult life tried to or wanted to write a play. I love description too much. And narrative voice.

Everyone else is either made up or a composite of many people, even if they’re somehow inspired by a real person or something about a real person. It’s a motley. More, it’s a motley designed and tacked together more than forty-five years after the time in which the novel is set, so it’s anybody’s guess what kind of distortions I’ve brought to even the most salient details.

My favorite character in the book, Katherine Klein, who keeps changing her persona (and name) and who too readily adopts the nickname “Anne Frank,” is completely made up. And naturally when you plop a made-up character into a world of “real” people and motley, distorted ones based on decades-old impressions from childhood, and when you have them all living through events that never happened, except in my imagination, they all become, in the end, imaginary.

TZ: What messages and lessons did the fictional camp teach the protagonist, Philip, about theatre, and about life? Are you (or were you) as jaded about these as teenage Phillip became?

TL: I was never as jaded or wounded as Philip becomes, though I did—in my last year at camp (I think I was 19)—have to ratchet up some anger and disillusionment in order to cut the cord and get on with my life. I’d spent 11 years at camp, and it had formed me and provided me with a sense of home I didn’t have in my real home. So yeah, a little late in adolescence, I had to propel myself out of there with a little peevish “you all suck” kind of fuel. Nothing like Philip’s, though, as his world is truly broken in a way mine never was, his spirit broken in a way mine never was.

Simply, though, I think the fictional camp—Friedkin—teaches him something that his parents, in their own brokenness, can’t: connection. It’s the lesson of theatre, too: you can’t do it alone. There are worlds of emotion, of spirit, of need and empathy and love that bind us, and those bonds are something you feel sitting in a theatre with others, however faintly. You feel them even more powerfully when you actually make theatre with others, when you sing together and dance together and listen and speak together. That human connectedness—“You’ll never walk alone”–the main lesson the Friedkin sisters teach Philip, and it’s the lesson he tries to refuse, to deny, at great cost to himself.

When History Comes Calling

TZ: One character takes on the persona of Anne Frank during her last summer at camp—a particularly poignant image as many of us “shelter in place” during the Covid-19 pandemic. Outside camp, too, much of the story involves the scars of Holocaust survivors and WWII vets. How do you see the relationship between these painful historic events and suburban kids at a summer theatre camp? How much do you see them driving the novel’s events, including Philip’s decision to “run away”?

TL: You’re so right that the image of Anne Frank and her family in their small “secret annex” has special poignancy right now, though of course we all hope the outcome of our sheltering doesn’t end tragically and catastrophically as theirs did. Your question about the relationship between those historic events and the suburban camp experience goes to the heart of what I was trying to understand. My own suburban life seemed so tiny, so sheltered and uneventful in comparison to the lives of my parents’ generation—depression, war, Holocaust, antisemitism. They’d literally constructed our lives to wall us off from all that, to deny horror by means of sheetrock and brick and 1/8th acre lots with newly planted elm trees and pleasant new elementary schools with well-trimmed play yards, and so on. They lived lives, and we put on shows.

[H]ow is history visited upon you, even when you don’t know it’s in the house? What does it mean to be part of a generation that lives in history versus one that seems to have witnessed almost nothing? What is suburban denial and what are its costs? What are the benefits of a theatre that transforms the tragic past into shared, present culture?

But, as we know, it doesn’t work that way. The past won’t be denied so easily. You can’t sing it away or landscape it away. Skokie, where we grew up, had one of the largest contingents of survivors in the nation. My father may not have spoken about his war trauma—we didn’t have a term for Post-traumatic stress—but that doesn’t mean it didn’t reside with us. And in our little cut of the baby boom (the peak that marked the boom’s end), even the Civil Rights struggle and the protests against the Vietnam war were seen through child eyes and, for me at least as a solidly middle-class white boy in a Jewish suburb, a bit romanticized.

So that’s what I wanted to know—how is history visited upon you, even when you don’t know it’s in the house? What does it mean to be part of a generation that lives in history versus one that seems to have witnessed almost nothing? What is suburban denial and what are its costs? What are the benefits of a theatre that transforms the tragic past into shared, present culture?

There are moments, of course, when history comes calling and you know it (if you’re old enough and cognizant or if you’re part of a population that takes the hit). Global pandemic is one such moment, as was 9/11, the AIDS onslaught and, for those of us who didn’t live in the blinkered shelter of postwar suburbia, the ever-present historical moment of American racism.

Literary Paths

TZ: You published this novel with British publisher Austin Macauley and mention how helpful their team was in your acknowledgements. (The editor in me immediately noticed the British punctuation, but I got over it.) What exactly is a hybrid publisher, and would you recommend that other writers consider it? Also, I see on your website that you have two other books due out this year. Can you tell me a little bit about them both?

TL: It was truly weird working on a novel set in the mid-20th-century American Midwest with a British publisher, and, while we were able to return to American spellings after a first round of edits, the punctuation caught me off guard. I’m afraid we never got it entirely right.

The two other books are very different, including that I worked on each of them for a mere six years, instead of eighteen. One is a strange non-memoir memoir I co-authored with the experimental theatre director Andre Gregory, best known as the co-creator and co-star of My Dinner with Andre, as well as film productions of his theatre work, including Vanya on 42nd Street. It’s called This Is Not My Memoir, and will be published by Farrar, Straus, Giroux. The other is a collection of fifty years of writing by the great American theatre pioneer and founder, Zelda Fichandler, who I’d been helping a little with her collection (for TCG Books) when she died in 2016. When she was too ill to work on it, she asked me to finish it for her, which I have recently. Both are now scheduled for the fall.

In part because I’d spent so much of my recent writing life on projects like these that began in other people’s work and life, it was important to me not to neglect my own baby, my novel. After twenty-plus books and a lifetime of writing professionally, I was too proud to self-publish and too impatient to spend more years circulating my novel to agents and publishers. My wife’s friend runs a publishing company for women writers called She Writes Press, and through her I learned about hybrid publishing, which functions a little the way festivals do in the theatre—a combination of curated, professional publishing and self-funded publishing.

It’s an interesting calculation: how badly do I want to get this book into the world, how long am I willing to wait, what feels like the right publisher, what feels like the right amount of self-push?

In the case of Austin Macauley, one of the fastest-growing independent publishers in the world, they select books that meet their standards and match their aesthetic values, and then have a scale of offerings that run from fully traditional publishing, covered and paid for by the publisher, to a range of up-front contributions from the author. In my case, I contributed a very little toward upfront costs—design, editing, proofreading, promotion and marketing, printing and distribution—and will get a larger than usual royalty on sales. So it flips the notion of advance.

It’s an interesting calculation: how badly do I want to get this book into the world, how long am I willing to wait, what feels like the right publisher, what feels like the right amount of self-push? As for the economics, after twenty books and thirty-five years as a professional writer, I doubt a single project of mine has yet—hours for dollars—earned me minimum wage. I mean, what would I have to make to compensate me for eighteen years of writing? It has made me a little humble about it all.

Funny, then, despite my queasiness about stepping off the more conventional literary path, I’m as proud of this novel as I’ve been of any other book. In theatre terms, it feels like I’ve brought the most important project of my life to the important Edinburgh Theatre Festival, paid the airfare and hotel myself, and been given a gorgeous production in the most beautiful space in the city.

Terra Ziporyn

TERRA ZIPORYN is an award-winning novelist, playwright, and science writer whose numerous popular health and medical publications include The New Harvard Guide to Women’s Health, Nameless Diseases, and Alternative Medicine for Dummies. Her novels include Do Not Go Gentle, The Bliss of Solitude, and Time’s Fool, which in 2008 was awarded first prize for historical fiction by the Maryland Writers Association. Terra has participated in both the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and the Old Chatham Writers Conference and for many years was a member of Theatre Building Chicago’s Writers Workshop (New Tuners). A former associate editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), she has a PhD in the history of science and medicine from the University of Chicago and a BA in both history and biology from Yale University, where she also studied playwriting with Ted Tally. Her latest novel, Permanent Makeup, is available in paperback and as a Kindle Select Book.

- Web |

- More Posts(106)