HOW DO YOU FIND A NOVEL?

Are you currently reading a novel? How did it land on your reading list?

Are you currently reading a novel? How did it land on your reading list?

Are you currently reading a novel? How did it land on your reading list?

Are you currently reading a novel? How did it land on your reading list?

Happy Holidays! As I contemplate the dismal political scene in this country, I am reminded of a quote from a 19th century suffragette whose name I don’t remember: “Take up your pen and save the world.” Or as Harriet Beecher Stowe said, “It’s a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.” She did that in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book that helped change this country.

Happy Holidays! As I contemplate the dismal political scene in this country, I am reminded of a quote from a 19th century suffragette whose name I don’t remember: “Take up your pen and save the world.” Or as Harriet Beecher Stowe said, “It’s a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.” She did that in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book that helped change this country.

In a google search of quotes on this subject, I found a column on Goodreads.com that features a number of quotes about taking up the pen. Most of them are banal or cynical, but here are a few that echo the quotes above.

Listening to James Michener’s Chesapeake on recent driving trips, I’m finding myself increasingly uncomfortable. He’s cheating, I think. These characters – they are so vivid. He didn’t have to make them up from whole cloth. Doesn’t that make his life as a novelist considerably easier? Or his creative achievements less impressive?

The holiday season finds me grateful for the profound reading experiences of childhood. Remember when reading a book was living the book? Certain books and authors left a mark on my reading, my writing, and my life. And for the reading of my childhood, I owe special gratitude to my great-aunt Mildred Campbell.

My grandfather’s baby sister Midge was small but mighty. She grew up on the family’s strawberry farm in Tennessee. Witty and determined, Mildred became a history professor at Vassar College. Her cozy house on College Avenue in Poughkeepsie was full of books─including a shelf for the Oxford English Dictionary. She loved books and words; talked a lot; read a lot; wrote a lot.

Researching a novel can involve more than history books, archives, and the other usual resources for honing details of terrain, lifestyle, time. What about describing emotions, personality, and the intangible nuances?

The subject came to mind in riding along with a police officer on patrol. I asked the officer what resources she found helpful and that led to a conversation about lying. One book she found very useful, the police officer said, was Spy the Lie by Philip Houston, Michael Floyd, and Susan Carnicero with Don Tennant. The authors are former CIA officers who use a methodology developed by Houston to detect  deception in the counterterrorism and criminal investigation realms. They show how these techniques can be applied in our daily lives.

deception in the counterterrorism and criminal investigation realms. They show how these techniques can be applied in our daily lives.

Ten Great American Political Novels for Trying Times

As the campaign season draws to a close, there’s one thing we can all agree on: Truth is, indeed, stranger than fiction. But what about fiction with a strong political theme? Can it help us understand and make sense of the world around us? You bet it can, and I’ve got just the list to prove it.

Whether you’re fed up with politics and need an escape or you just can’t get enough of it, here are ten American political novels worth considering before Inauguration Day. The choices are mine, and I’ll warn you that I’ve left out a few that might seem particularly partisan (Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, for example), as well as the many great foreign political classics (1984, The Trial, War and Peace, to name just a few).

If people join book clubs – or don’t – it’s mainly about the books. Or at least that’s what people claim.

If people join book clubs – or don’t – it’s mainly about the books. Or at least that’s what people claim.

As a children’s book blogger and mother to a toddler, I’m an equal-opportunity lover of books, from board books to novels, and I’ve learned to largely ignore age recommendations. That’s how I found Catherynne M. Valente in the children’s book section rather than general fiction, and, trust me, she’s not an author to miss, no matter how you find her.

I first encountered Cat Valente’s books through her Fairyland series, novels which are listed for ages 10-14, according to the back cover. I’m 29 right now, by the way. I soon finished reading them all and delightedly reviewed them for my children’s books blog, The Children’s Bookroom, praising her for her ability to frame characters with such heart and personal growth, and to create a world so fantastical and yet so tangible.

I consider myself a novelist not a short-story writer. In fact, I’m not satisfied with any of the three-dozen shorts in various stages of development that occupy a directory on my harddrive. Writing short stories is very different than writing novels. Some people think it’s best to start out with shorts and then move on to novels. That may work for some, but to me it’s like thinking you would be good at bull-riding because you can ride a horse.

A novel is not just a long short story. Psychologically it requires a much greater commitment because it can take months or even years to complete a 90,000-word novel. Most short story writers don’t need help deciding when their story is ready for public consumption.

Naiveté, desperation, eagerness. What does that spell to you? To me it spells V-I-C-T-I-M. It can also spell W-R-I-T-E-R.

A writer eager to find a publisher, desperate for an agent, naive enough to sign any contract that seems to promise an agent and publication. And that’s just the dirt on top. Dig a little deeper and you’ll find all kinds of “opportunities” to promote, sell, distribute or otherwise handle a writer’s opus—for a fee.

I have been a writer all my professional life and a publisher for the last twenty plus years. I know how eagerly a writer wants to be published; I know the anguish of being rejected again and again by uncaring and by, obviously, ignorant agents who can’t seem to grasp my vision.

You Should Look It Up

Kids hate dictionaries. That’s something I’ve discovered over fifteen years of tutoring elementary and middle school kids. If they come across a word they don’t know, they’d rather ignore it than go to the bookcase for a dictionary.

Kids hate dictionaries. That’s something I’ve discovered over fifteen years of tutoring elementary and middle school kids. If they come across a word they don’t know, they’d rather ignore it than go to the bookcase for a dictionary.

I couldn’t help thinking about that last month when I stopped by 17 Gough Square in London, the home of Samuel Johnson from 1748 to 1759, which is when he and a staff of six were hard at work compiling The Dictionary of the English Language [volume 1 and volume 2]. Visitors are welcome in most rooms, and all the exhibits give a taste of the Georgian life Johnson and his friends led. My favorite spot was the attic, where most of the dictionary work was done.

“You’re in a book club?” my friend asked incredulously. “Why would you join a book club?”

I was a bit surprised to be asked this question by a friend who also happened to be a professor of comparative literature. We had known each other since college. We are both writers. I had just told her that our next meeting would discuss Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, a book she greatly admired. So why was it so odd to her that I was in a book club?

“I can’t imagine being in a book club,” she said. “That’s what I do for a living.”

My Take on Plotting versus Pantsing

A common writers’ conference workshop topic is “Pantsing versus Plotting,” a reflection of the fact that many writers struggle with how to plot out their stories. If that’s you, perhaps my breaking down this issue will help you gain some insights into how to avoid some of the pitfalls of poor plotting.

The Writer as Superman or Superwoman

Naturally I also admire artists and writers who are unexceptional at anything but their art. Nevertheless, the lives of people who do nothing but write or paint or make music, often seem barren or bleak. Who would want to live Kafka’s life, or Woolf’s, or Joyce’s? I have long been fascinated by multi-faceted geniuses like Leonardo, Michelangelo or Goethe, and those who performed great physical feats. Heroes live full lives. And by ‘heroes’ I don’t mean that we must approve of everything they did. But it’s useful to reflect on those artists who live on a grander scale, who consciously or unconsciously try to live as supermen or superwomen.

On a recent trip to Florida, my husband, some friends, and I took a short boat ride out to an uninhabited barrier island. We hiked out to the beach, and they pulled up a seat while I continued on to hunt shells. I was perhaps a quarter mile away when I decided to take a quick dip to cool off. As I turned to go back to shore, a searing pain burned through my foot. I stumbled out of the water, fell onto the sand, and watched as blood pumped with every heartbeat from the top of my foot. The pain threatened to cause a blackout.

Here are the things that went through my mind as I sat there:

Lifelong Learning, necessary for everyone, is especially relevant for writers. The range of skills and knowledge needed to write well and successfully exceeds infinity. A writer’s basic attribute has to be curiosity.

I belong to the Maryland Writers’ Association, which has chapters around the state, each holding monthly meetings with speakers. The past week, I was fortunate to attend the Carroll County Chapter meeting with author Toby Devens and the Howard County Chapter meeting with author Nancy J. Alexander. Toby writes witty books about women’s friendships and struggles; Nancy is a retired psychotherapist turned author who writes the Elisabeth Reinhardt series of psycho-thrillers.

So in one week, I got a quick course in the importance of researching the facts in a novel from Toby and another quick course in developing characters from Nancy

When Borders set up shop in Overland Park, Kansas, in the early 1990s, my fellow writers and I mourned for what we believed was the impending doom of our local bookstores. Some of us had relatives who ran local stores, and those shopkeepers told us they could never compete with the mega-store on price or selection of books. And for years it seemed they were right. One by one the local bookstores dropped out of existence. Things looked even bleaker a few years later when Amazon.com burst onto the Internet and began sucking up the book business. But today, the future of independent bookstores has taken on a whole new shine. Articles in prestigious publications including Time, Forbes, Salon, and The New York Times herald the news that indie bookstores are not dead.

If you could own a physical copy of just one book, what would it be and why? I asked this question last month and got a wide-variety of answers. Not surprisingly, several people chose the Bible, a single book that served the vast majority of people since the dawn of book publishing and ownership just fine. Other top must-haves for the digital age included cookbooks and other guides, marked-up editions, collections, and a random assortment of personal favorites, including memoirs, social analyses, and fiction.

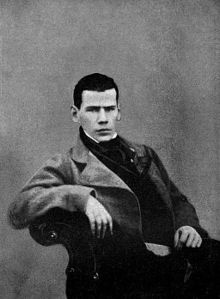

I’m shocked when I read lists of favorite novels and see that most, and sometimes all, are American. There may be a leavening of British authors too; that’s something. Still, I think, haven’t you read the Russians or the Germans? You really think Toni Morrison or Jonathan Safran-Foer are better than Tolstoy or Musil? Anglo-Saxon culture is lamentably insular, and American culture is not merely insular but downright provincial these days. The greatest weakness of the writing done by creative writing students—graduates as well as undergraduates—is that it’s so rarely informed by wide reading. And however unfashionable it may be, my remedy is to send them to the canon. Not “back to the canon”, sadly, because most of them aren’t familiar with it in the first place.

I’m shocked when I read lists of favorite novels and see that most, and sometimes all, are American. There may be a leavening of British authors too; that’s something. Still, I think, haven’t you read the Russians or the Germans? You really think Toni Morrison or Jonathan Safran-Foer are better than Tolstoy or Musil? Anglo-Saxon culture is lamentably insular, and American culture is not merely insular but downright provincial these days. The greatest weakness of the writing done by creative writing students—graduates as well as undergraduates—is that it’s so rarely informed by wide reading. And however unfashionable it may be, my remedy is to send them to the canon. Not “back to the canon”, sadly, because most of them aren’t familiar with it in the first place.