Insights

The Serious Side of Humorous Novels – Our Parent Who Art in Heaven Included

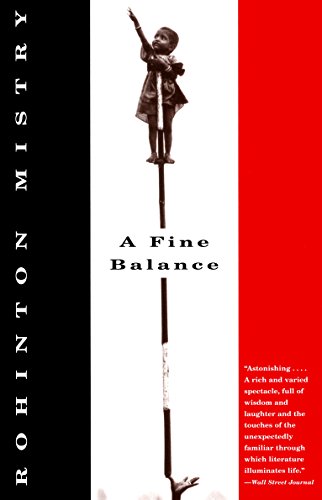

So far nearly all the Goodreads reviews of my novel have emphasized how funny it is – which is gratifying, because it is a comedy, and humour is so hard to pull off. However, the best comedy usually takes as its theme issues of real importance, and it’s even more gratifying when readers understand the underlying argument as well. Evelyn Waugh in Vile Bodies was not merely ribbing the Beautiful Young Things of the 1920s, he was also showing how shallow and futile their lives were, and for me this tendency culminates in A Handful of Dust, which begins as a hilarious satire on the upper classes and the social climbers trying to enter that class, but ends up with real tragedy – the death of a small boy which is made all the more shocking because when his mother hears about his death, she is relieved, because her son shared the name of her lover, and her initial grief was for the latter.

So You Don’t Like That Character—So What?

Lately I’ve been reading books with unsympathetic characters. This is not a new habit, but since finishing the draft of a novel whose characters are imperfect but, I hope, likeable on the whole, I’ve been thinking more about what makes a character likeable, and what the difference is between likeable and admirable. Fiction (to say nothing of history) is full of protagonists we might not like but can still respect and admire. Heroes whose achievements we celebrate but whom, given the chance to sit down and have a beer with, we’d just as soon avoid.

I’m not thinking either of the truly reprehensible—antiheroes like the talented Mr. Ripley. Though I must say that Patricia Highsmith’s ability to make a reader care about a serial murderer deserves admiration in itself.

Why Huw, the Hero of Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, May Be a ‘Boyo’

Do you know what a ‘boyo’ is? The Urban Dictionary defines it as ‘An endearing term used to refer to (young) men searching for the meaning of life through the works of Jung, Freud, Nietzsche and other such psychologists/philosophers.’ I have only become aware of this meaning in the past couple of days. And yet, by happenstance, Huw, the Welsh hero of Our Parent Who Art in Heaven (Flame Books, 2022, already available for pre-order), often addresses himself in his thoughts as ‘boyo’, the traditional Welsh or Irish form of ‘lad’ or ‘dude’. In our age, when young men so often feel emasculated, neutered, and lost – when so few of them have had real present fathers who confirmed them in their manhood, and when so many of them have been told in the course of their education that they should behave more like girls, be nicer, less aggressive – vast numbers of young men are trying to confirm themselves, give themselves the rite of passage they never had, and become more self-assertive, self-affirming.

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES

Books That Changed My Friends’ Lives

In my last blog I asked if books change lives. The resounding answer I got from Facebook friends and family was yes, of course. I also ended up with a long reading list that keep me busy for the rest of the year, and likely beyond.

Books That Create Readers

Many of us grew up assuming that books change lives. We assumed the books we read at school were life-changing. We had lists of classic books and trendy books and devoured them, changed by each and every one. For natural readers, the mark of a “good” book is, of course, the mark it leaves on you.

But not all books that change lives are “good” or “classic” or “literary.”

The Future of Fiction – the Superman/Superwoman or the Snivelling Slave

This is the weekend of the Oscars – an event most of us now avoid, because of its tedious and hypocritical virtue-signalling and moralising. (Not to mention the clips from all-too-predictable, formulaic films.) This has me wondering and worrying whether literary fiction will also become irrelevant. In a sense it already has. Few men read ‘serious’ fiction any more, although when I was young, half the readers were men. And I suspect that most of the women still reading the latest lauded offerings do so only so that they are not left out in conversation at dinner parties. I know women who have admitted to me that that is why they read.

Celebrating Obscurity: “The Necrophiliac” by Gabrielle Wittkop

I would never have encountered Gabrielle Wittkop, or her symphonic poem of a novella, The Necrophiliac, were it not for the serendipity of meeting its translator, Don Bapst. Bapst, an American-Canadian filmmaker, screenwriter, novelist, and poet, translated The Necrophiliac into English in 2011 (ECW Press, Toronto). The translation, heralded as a “masterpiece” by Nicolas Lazard of The Guardian, has provided English-language readers an incomparable entrée into the sensual, poetic, and genre-blending genius of Wittkop’s astonishing prose. The story—to reassure those readers already squinting their eyes against assumed revolting or gratuitously shocking material—is shaped as diary entries by the protagonist, Lucien, an exile of Renaissance intelligence and refined aesthetic discernment, whose beguiling sexual fluidity and emotional loyalty happen to find their fulfillment in a series of affairs with recently-deceased women, girls, men, and boys.

Not Just Our America

Here’s another really incise comment from my friend, Luis Othoniel Rosa, whose words have been featured before on LLNB (Spanish-to-English translation by me, so if any of it is less than clear, it’s my fault):

“One of the great essays of Latin American criticism is titled, ‘Our America: The Art of Good Governance;’ it a marvelous close reading of (Cuban writer and patriot) José Martí by (cultural critic) Julio Ramos. Immediately upon contextualizing the brutal critique by Martí of the intellectuals of his time and of the global project to modernize, Ramos tells us that many decades ago, Martí constructed a new authority by means of the form and style of his writing: literature. Literature, according to this legitimizing strategy, was the discourse that could yet represent origin, the autochthonous, and all those margins that rationalizing languages, emblems of modernization, could not represent.

All Books Aren’t Blue, or The Books Themselves Should Have Standing

Normally I’m not too interested in entering political debates over literature and culture. Suffice it to say that most literary scholars are firmly left of liberal and that I usually agree with their politics; but when it comes to discussing cultural theory and interpretation, I’m often the conservative in the room. More on that some other day. Maybe.

I’m also not too interested in young adult literature. I don’t have children, and Harry Potter, for some reason, just doesn’t speak to me. My idea of great writing for young people runs from Shirley Jackson’s psycho-horror to Uruguayan Horacio Quiroga’s brutally naturalist tales. (His most famous, “Juan Darién,” portrays a boy changed to a tiger who is literally hunted down, tortured and left for dead by the rural community that fears him.)

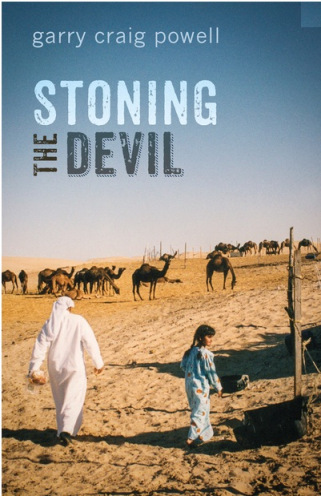

Praise for Stoning the Devil from a Postcolonial Feminist Scholar

I recently discovered a superb scholarly review of my first book, by a self-described ‘intersectional feminist’. In the abstract to ‘Orientalism and the Failed White Saviour: A Study of Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning the Devil’, (2020)Dr Rathwell writes that my collection of linked stories ‘delivers a critique of Western white expatriate saviourism by presenting a nuanced relationship between his British protagonist Colin, and his Palestinian wife, Fayruz. Through the use of meta-literature, anti-hero tropes and references to violence and sexuality, Powell critiques stereotypical tropes of Orientalism. (…) complicat(ing) them in a literary manner to provide biting criticism of white saviorism in the Middle East. The relationship between Colin and Fayruz therefore serves as a metaphor for relations between the West and the Orient, and in doing so, questions if there can be a post-Orientalist world.

Literary Translation Today—A Lament, a Shout-Out, and a Totally Random Guide

What gets translated into English by whom is an occasional but painful topic among writers, readers and scholars of foreign literatures. The answer is consistently and increasingly, “not much, and mostly writers that are already best sellers.”

The problem is emblematic of the American market, which is shrinking for fiction in general and almost nonexistent for foreign fiction (proof that American isolationism is still a thing), but which can be a gold mine for that very rare foreign thriller or Nobel Prize winner. Milan Kundera and Orhan Pamuk will have contracts for English translations even before their next novel is published in Czech or Turkish; By contrast, Paula Maia, the award-winning writer from São Paulo, Brazil, has published ten books, only one of which has been translated into English– Saga of Brutes, a triptych published in 2010 and translated six years later.

DO BOOKS CHANGE LIVES?

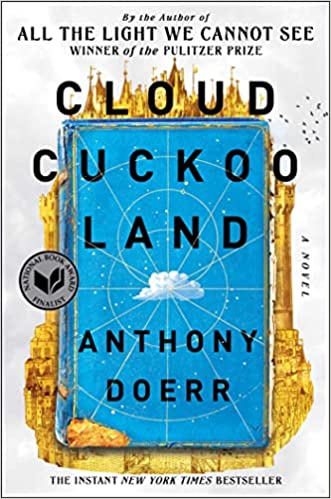

Our family New Year’s celebrations are tame (and aren’t they all these days?). We dipped fondue around a fire, “Zoomed-in” absent family members, and answered questions that forced us to reflect, reminisce, and prophesize. One question asked us to name a book read in 2021 that had changed our lives.

Do books change lives? My husband claimed he was too old to be changed by a book. But after listening to the rest of us report out, even he admitted that reading could change his life, at least a bit.

Our Family Favorites

Within a blink of the eye my daughter named named Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, a book about fungus of all things that offers a profoundly new way to view the world and our place in it.

BOOKS THAT GOT US THROUGH 2021

Last month I asked readers of this blog–and my friends–to help build a list of books that got us through 2021. Now that December is upon us, I’m delighted to share it. It’s a little different than the bestseller lists, so maybe it will give you some new gift ideas–or new year’s resolutions?.

I wasn’t interested in the top-selling or most-read books of 2021. I just wanted to know what people most enjoyed reading in the year we’re about to lose.

Some of these were on my 2021 list too. But there were many surprises that truly expand my reading horizons. And, interestingly, quite a few of the books, even the many about dystopias, illness, and warfare, were packed with hope.

What Does It Mean to Be Disruptive in Literature Today?

The following is an imperfect translation of a commentary by Luis Othoniel Rosa, writer, poet, anarchist and scholar who, among other things, teaches Latin American literary studies at the University of Nebraska. Luis’s original text in Spanish follows my translation.

What Does It Mean Today to Be Disruptive in Literature?

It means to affirm and to stop making ourselves of interest. Being disruptive in literature today would be to put an end to the era of questions and paradoxes, of undecipherable allegories and of the “writing of the self,” where the children of the white middle class write novels and poems about the silly traumas of their insipid lives. Being disruptive would be imagining possible worlds and manufacturing bold, new mythologies without fear of getting it wrong because it is no longer the writing self that matters, but the collective mind that thinks by means of our writing.

BUILDING A READER FAVORITES LIST FOR 2021

As we careen toward December, I’m realizing that 2021 will soon be relegated to another heap of memories. So it seems like an appropriate time to build a list of reader favorites for the year. And what better way to do it than by asking Late Last Night Book readers for suggestions?

Your Favorite Book of 2021

Fiction or non-fiction, just published or dusty–it doesn’t matter. It will just be fun to put together a reader favorites list for next month’s blog featuring the books we’ve enjoyed in 2021.

I suspect there will be some surprises.

Whether I’ll find anything profound to say about that list remains to be seen.

Schopenhauer’s Advice: Don’t Read So Much!

Recently I’ve been following a YouTube channel called Weltgeist, which deals (exclusively, I believe) with the philosophy of Schopenhauer, and to a lesser extent, Nietzsche. This has prompted me to re-read The World as Will and Representation, the great pessimist’s magnum opus. But Schopenhauer had opinions on nearly everything, as his entertaining (and occasionally outrageous) essays show, including reading and writing. And since he was one of the few philosophers who had a clear and elegant prose style himself, and since he was clearly one of the greatest intellects of recorded history, it may be worth considering what he had to say on the subjects.

First of all, he cautions us not to read much. This is pertinent, when so many people aim to read a book a week, or more – one of my friends felt guilty if he could not manage to read two or three books in a week.

Is It Weird or Is It Human?

About thirty months ago, Gary Garth McCann, my husband, founder of Late Last Night Books and the author of several works of realist fiction, suffered a massive stroke. I won’t detail the myriad ways this cataclysm has changed our lives. The changes his brain injury has wrought in his writing, however, are worth discussing here. It recently dawned that these changes relate directly to a question that has preoccupied me for some time: how we perceive reality, how we represent it, and the ethical implications of what we deem to be weird or unreal.

The accepted parameters of “weird literature,” parameters set by American writer HP Lovecraft in the 1920s, state that weird writing provokes disgust and discomfort, forcing readers to question their relationship to reality.

A CRASH COURSE IN CLARITY: TIPS FOR EFFECTIVE SCIENTIFIC WRITING

Note: This article was originally commissioned by and published in The Singapore Microbiologist, July-September 1997 and republished in Medium.com on September 2021. While the article focuses on scientific writing, writers of any sort should find the tips useful.

In my many years editing scientific manuscripts I have discovered two extremely common myths about writing. The first is that the more obscure you are, the more profound. The second is that all people could write well if only they had enough time.

To some extent, I’m grateful for these myths (after all, the provide me with a decent living). On the other hand, they’re both dead wrong, and they lead many otherwise excellent studies to go unpublished and unrecognized. In this article, I briefly discuss each myth, hoping to convince you that writing clearly is a worthwhile goal for any scientist, at least any scientist who expects to be published in a major journal.

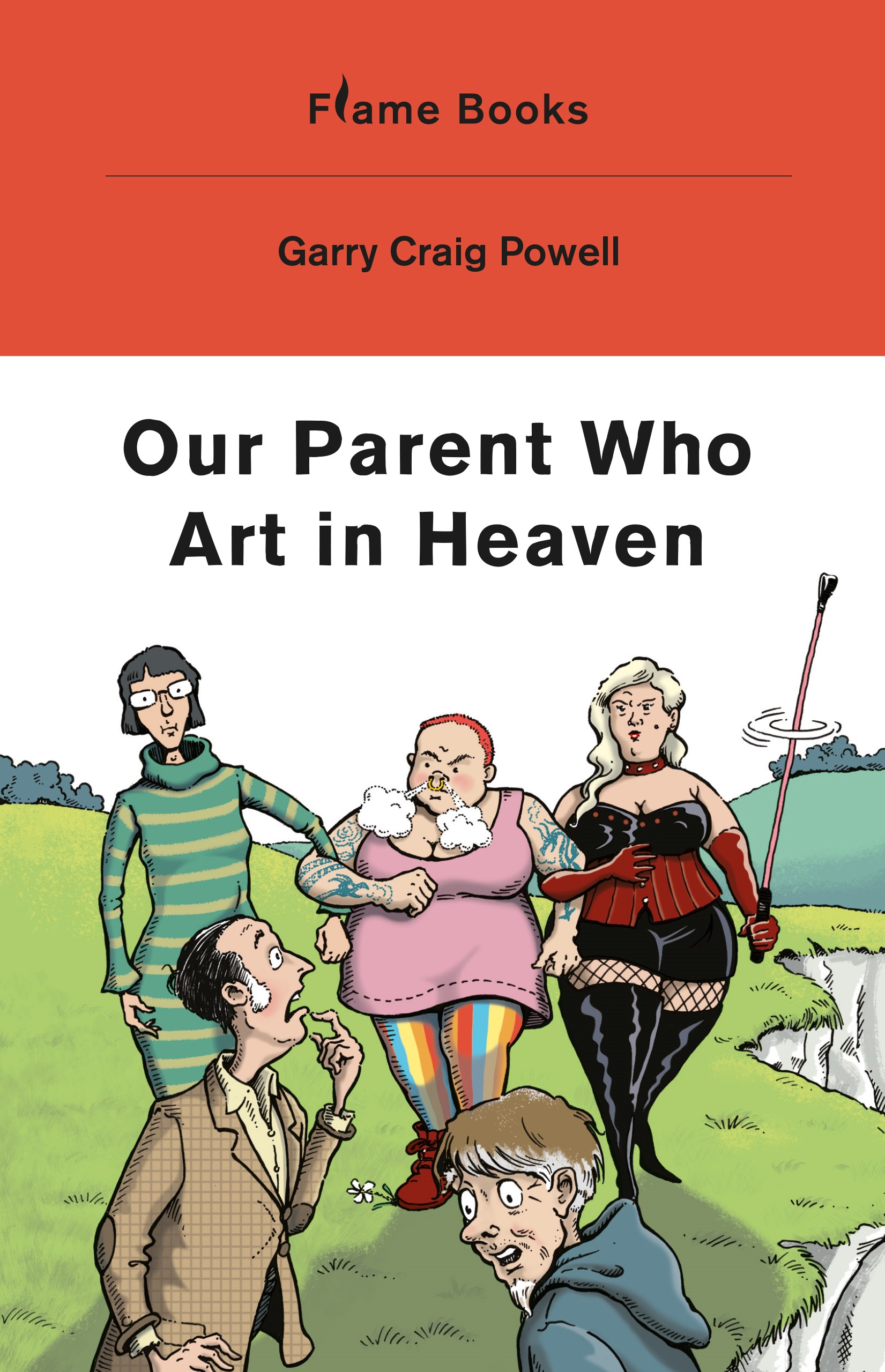

The Birth of a Book by a Big, Bad, British Author

Cover Illustration by Nick Ward

Here’s the news: nearly 10 years after the publication of my first book, Stoning the Devil, Flame Books of Scotland (a new press – their website will be up within a couple of weeks) are going to publish my second, the satire Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, in late March 2022. Writers customarily preface such announcements with apologies for their ‘shameless self-promotion’ but I won’t. There’s none of that here. I don’t expect this novel to make me rich or famous, and I don’t even want that. I do want the novel to reach an audience, because in its no doubt modest way, I think it’s important.

What’s it about then? Here’s the blurb on the back cover:

Welshman Huw Lloyd Jones’ life seems perfect: he teaches Creative Writing at a charming college in the American South, and is happy with Miranda, his beautiful wife.

Old Souls, Youthful Dysfunction, and Children Parenting Their Fathers.

My last post dealt with weirdness in fiction. This post is an extension of that topic, related to two works I’ve read recently. The first of these is Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Goldfinch, which I’ve only just gotten around to reading. (It’s nearly 800 pages long–that’s my excuse.) The second is a nonfiction memoir, Not the Kennedys, by a very talented newcomer, John O’Hern, who happens to be my cousin by marriage. These two books have absolutely nothing in common except that I happened to read them in the same month, and that both triggered more thoughts about how we humans confront an incomprehensible and incoherent world by writing about it.

The Goldfinch is, in my unhelpful opinion, less original and less spectacular than critics have made it out to be (maybe my next post will be about the weirdness of literary prizes).

Can Fiction Writers Stem the Tide of Barbarism?

The barbarians are no longer at the gates, but inside them – and I’m not talking about invaders from other cultures, but homegrown barbarians who are either ignorant of the glories of Western culture, or actually despise it and want to destroy it. Anyone who supports cancel culture, for a start, which may mean the majority of the people you know, if you’re an educated person in the liberal professions – is a barbarian, someone with a medieval mindset who not only believes in strict orthodoxy, but wants to enforce it through ostracization. And the publishing industry is peopled almost entirely by these latter-day Goths, Vandals, and Huns.

This is all obvious to anyone who’s paying attention. The problem is that most writers have not been paying attention.

How Weird is That?

Literary scholars recently seem to think they’ve invented a new genre: weird literature. It’s partly an outgrowth of the increased popularity of science fiction, dystopic fiction and zombie stories–that sort of thing. Scholars also point to the restitution of the writing of HP Lovecroft (USA, 1890-1937), which seems to define this genre. I don’t have a problem with any of this (having been asked to contribute to a volume on the subject), but it’s worth pointing out that weirdness in narrative is nothing new, dating back at least to Cervantes’s Don Quixote, credited with kickstarting the modern novel in 1605. Don Quixote’s problem (the character’s “real” name was Alonso Quijano) was his inability to disentangle reality from fiction and his insistence on attacking the world as if it were an adventure tale from the chivalric tradition of “knight errantry.”

Roz Morris Talks to me about her new novel, Ever Rest

I’ve just had the pleasure of interviewing Roz Morris, who is English and the author of three novels, a travel memoir and a series for writers. She once had a secret career as a ghostwriter, where she sold 4 million books writing as other people, but is now obeying the commands of her own soul, which are to write literary fiction with a strong sense of story. She is also an editor and writing coach, and has taught masterclasses in Europe and for The Guardian newspaper in London.

We mainly discuss Ever Rest, (Spark Furnace 2021), her just-published novel. The premise:

Twenty years ago, Hugo and Ash were on top of the world. As the acclaimed rock band Ashbirds they were poised for superstardom.

Are Gardens for Real?

Ask any gardener. We’ll tell you that gardens are real enough–made of tangible living material and soil. But they are also products of the imagination, like any art form. And they are cultural products. Just compare the typical American garden–diverse, open, slightly wild–to the gardens characteristic of (in order of increasing formality) England, France, Italy, or Japan, respectively. Each culture imbues its gardens with its own peculiar approach to managing reality.

Because, after all, that is what a garden is–managed reality. A constant balance between the natural and the synthetic, between what we infer the natural world to be and what we want it to become. Between the ungraspable chaos of the natural universe and the aspirational coherence of our human minds.

LOOKING FOR AUTHORS (AGAIN)

If have written a book lately (or not so lately), we’re still looking for authors to be interviewed on Late Last Night Books!

A publicity opportunity

Once again, I am looking for authors who want help publicizing their books or writing project in future blog posts. In my experience, getting your name and work “out there” is the most painful part of being a writer. I’m hoping this blog can help make that process a little less painful for others–especially writers (and that’s most of us) who don’t have well-funded publicity machines working on our behalf.

In the past this offer has brought forth many talented writers, including Todd London, Harriet Arden Byrd, Bill Woods, Nancy Burke, Lila Iona McKenzie, Anna Marsh, and Michael J.

Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat

Leo Tolstoy – the greatest novelist of all – and yet lots of readers, even serious ones, have never read him. Why? Partly it’s because his two most famous works, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, are on the long side. That’s true, but even so, if you read just an hour a day, and typically read a short novel in a week, it might take a month to read Anna Karenina, and six weeks or two months to read War and Peace. Not that long. And you’ll probably read them faster, because they’re so good you’ll find yourself reading more at weekends and on evenings when you have time. But let’s say you’re really busy, and intimidated by these monuments of Russian literature.